“What y’all lookin’ for?”

My wife and I had stopped at Papa’s Foods in Linden, an out-of-the-way town of 1,800 souls and the seat of Marengo County, Alabama, for an off-the-shelf lunch. Not being part of the usual parking lot pageant, we drew inquisitive stares and queries.

Riding into the parking lot, a friendly (white) fat woman — so fat she had doughy excrescences protruding from her elbows and knees, creating bottomless dimples — decided to engage us. “Lunch,” I responded.

“Oh, you won’t find lunch in there,” she declared authoritatively, and recommended David’s Catfish House. I told her we’d be fine with cold cuts and orange juice. She looked puzzled. In the South, “lunch” is called dinner, conventionally the biggest meal of the day; while supper, the evening meal, is light — the opposite of a long-distance touring biker’s custom.

Suddenly one of them realized what I was talking about and quipped, “What, you ride dem bikes through the forests and swamps?”

As we ate our lunch under the shade of Papa’s Foods’ generous eaves, a tall, young black man, dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, baseball cap facing forward, and accompanied by friends of approximately the same age and disposition, asked, “Where y’all ridin’ to?”

“We’re riding the Underground Railroad from Mobile to the Ohio River,” I replied.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“Those boys don’t know nothin’!” declared a refulgently obese black woman sitting in the driver’s seat of an old, purplish Buick. She was awaiting the return of whoever was doing her shopping and decided to join our conversation to pass the time, a behavior we found rather common throughout Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky. It was apparent that doing anything but sitting would be a major undertaking for her.

I started to explain to the guys what the Underground Railroad was, when suddenly one of them immediately realized what I was talking about and quipped, “What, you ride dem bikes through the forests and swamps?”

We all burst into laughter. They wished us a good ride and entered the grocery store.

“Who’d you vote for?” asked the lady in the car.

Not skipping a beat, Tina answered, “Trump.”

“But he’s such a liar!” exclaimed the lady.

The density of churches in the Bible Belt must be seen to be believed. Some tiny hamlets boasted more churches than residences.

“All presidents lie,” responded Tina, adding that, “I look at policy results . . .” At that point the woman’s companion emerged from Papa’s with a dozen grocery bags dangling from his arms.

“You seem like smart folks,” the lady said, by way of a reluctant goodbye.

“We could talk for hours,” Tina responded.

As we saddled up to ride out of the parking lot, we spotted an extraordinary site, extraordinary because the density of churches in the Bible Belt must be seen to be believed. Some tiny hamlets boasted more churches than residences. Little Linden alone has more than ten churches, with as many nearby outliers. A middle-aged black woman, fat but not obese — everyone seems overweight in the deep south — dressed in purple shorts, wore a bright yellow T-shirt that proudly exclaimed in big purple letters: God is Dope.

I rubbernecked back and said, “I like your T-shirt.” She smiled and thanked me.

On the ride out of town the boys who’d engaged us at lunch passed by, all crammed into a pickup truck. They gave us a wide berth, hooted their horn, hung out the windows shouting encouragement, and gave us their thumbs up.

The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad (UGR), a dendritic network of harrowing stratagems and hidden routes, safe houses and sympathetic people willing to risk arrest to aid escaped slaves reach freedom in Canada (and even Mexico), was complex and extensive. And not just in slaveholding states. After passage of the revised Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which required escaped slaves to be returned to their owners even if captured in northern states, Canada became the only assuredly safe destination for them.

What came to be called the Underground Railroad was organized in the late 1700s in conjunction with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, a law that was otherwise mostly ignored. Underground Railroad . . . a curious name. Historian Robert C. Smedley, in his 1883 study, provides this popular, albeit unverified, version of how the name came to be:

In the early part of the UGR slaves were hunted and tracked as far as Columbia, Lancaster County [Pennsylvania]. There pursuers lost all trace of them. The most scrutinizing inquiries, the most vigorous search, failed to educe any knowledge of them. These pursuers seemed to have reached an abyss, beyond which they could not see, the depths of which they could not fathom, and in their bewilderment and discomfiture they declared that “There must be an underground railroad somewhere.”

The railroad conceit carried over into the lingo. Slaves were known as passengers or cargo; guides as agents or conductors; hiding places were stations, while station masters hid slaves in their homes.

While William Still, often called the “Father of the Underground Railroad,” was a freeborn black businessman and philanthropist who helped as many as 800 slaves escape and kept short biographies of each, it is Harriet Tubman who is the more familiar conductor. Her bold escapades belie her gender and unprepossessing appearance. She was ruthless in her determination and unyielding in her, what we might today term, charismatic faith. Still describes her as “a woman of no pretensions, a most ordinary specimen of humanity.” Charles L. Blockson, a black historian and descendant of a passenger, in his Underground Railroad: Dramatic First-Hand Accounts of Daring Escapes to Freedom, reports the following about her:

Tubman always carried a pistol to ward off pursuers and opium to quiet crying babies. Whenever her passengers became frightened and threatened to leave, she would slowly raise the pistol and declare, “Dead niggers tell no tales. You go or die.” Later she proudly proclaimed, “I never run my train off the track, and I never lost a passenger.”

In 18 harrowing expeditions she personally freed “somewhat over three hundred” slaves, according to her biographer Sarah Bradford. One estimate by Lisa Vox, archived at the Wayback Machine, suggests that, by 1850, 100,000 enslaved people had escaped via the network. Historian William H. Siebert, in The Underground Railroad, estimates that perhaps half that number went all the way to Canada.

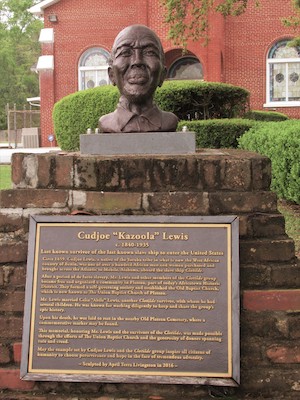

Our specific biking route, labeled the Underground Railroad Route, was put together by Adventure Cycling. It begins in Mobile, Alabama, a poignantly appropriate location, and ends in Owen Sound, Ontario. It starts in Mobile because that city was the site of the landing of the Clotilda, the last (illegal) slave transport from the West African Kingdom of Dahomey (now Ghana) to dock in the United States. It bore a cargo of 109 Africans, and landed in July 1860. The second-to-last of those surviving slaves, Cudjoe Kossola Lewis, a Yoruba, was interviewed by Zora Neale Hurston, a black, libertarian anthropologist, in 1927 (see my review of her book, Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo, in Liberty’s “The Last Cargo,” October 11, 2019). Mobile is also believed to be the site of the last recorded lynching of a black person in America, Michael Donald, in 1981. Nineteen-year-old Donald was picked at random by two members of the Ku Klux Klan, angry that a jury had failed to convict another black man accused of killing a police officer (The Economist, April 24, 2021).

Slaves were known as passengers or cargo; guides as agents or conductors; hiding places were stations, while station masters hid slaves in their homes.

The slaving expedition was organized by the Meaher brothers, entrepreneurs with fingers in lots of pies, including a sawmill in Mobile Bay. As the Clotilda approached Mobile, they heard that federal authorities were on the lookout, so they unloaded their cargo at night, and torched and scuttled the schooner in the Mobile River delta. While some of the Africans were immediately sold through prior arrangements, about 30 were retained by the Meahers and employed at the sawmill and on their farms. In January 2018 an underwater archaeological find labeled 1BA694 was tentatively identified as the Clotilda from preliminary collections, dimensions, and dating. As of this writing, no plans have been made for further excavations or recovery of the Clotilde.

North of Mobile, the route parallels first, the Tombigbee River, and then the Tennessee River to the confluence of the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers, the latter constituting the boundary between slave and free states. Slaves were kept illiterate and ignorant of geography, yet, through word of mouth they knew that freedom could be found to the north. Following African tradition, important knowledge would be encapsulated in song. Such was the Drinking Gourd song, a rough guide to the route north from the Mississippi and Alabama areas. The drinking gourd referred to the Big Dipper, a handy reference to finding Polaris, the North Star. According to some interpretations, individual stanzas provided coded information as to when to head out — it could take a year on foot to reach the Ohio River — which waterways to follow, what cryptic signposts carved on tree stumps to look out for, and other useful information that might have been elaborated on verbally.

Alabama

Our ride was to begin on April 1 from Meaher State Park on Mobile Bay by riding into and doubling back from Mobile proper. The park had been donated to the state by a descendant of one of the original slave smugglers, Timothy Meaher (a man who had been charged with the crime but never convicted). We were very apprehensive. The April 1 weather forecast called for a possible tornado. The storm arrived at 1 AM, tested our camper van’s integrity, but dissipated by dawn. We parked the van in the park’s long-term parking and headed out.

Immediately after crossing Mobile Bay, we hit Africatown, the settlement established by the emancipated slaves from the Clotilda, on land bought from the Meahers in a purchase negotiated by Cudjoe Lewis. The Cudjoe Lewis Memorial Statue stands at the entrance to the settlement, in front of the historic Union Baptist Church, which Cudjoe also helped found.

Africatown has seen better days. The homes we saw were in advanced states of disrepair, although the roads were in good condition. An empty lot with gates akimbo, labeled “Future site of the Africatown Visitor Center” and across the street from the Africatown cemetery, was riddled with garbage and disregard.

We rode on into Mobile proper, headed for the corner of St. Louis and Royal Streets, site of one of the busiest slave markets in the South. That market became an embarrassment even to Mobile’s city fathers. In time they banned slave depots from the downtown area, so Alabama’s principal slave market upped stakes to Montgomery, first capital of the Confederate States of America.

Back then (1860 census), 45% (or 435,080) of Alabama’s population was in slavery, with another 2,700 free blacks choosing to stay there, mostly in urban areas. And Deep it was. According to Philip Younger, an escaped Alabama “passenger” in the UGR who made it to Canada and settled in Ontario, “escape from Alabama is almost impossible — if a man escapes, it is by the skin of his teeth” (Blockson, 1987). Today, blacks constitute only 27% of Alabama’s population.

The weather forecast called for a possible tornado. The storm arrived at 1 AM, tested our camper van’s integrity, but dissipated by dawn.

On the second day’s ride we headed north along the Tensaw River. After Spanish Fort the route entered deepest Alabama. Mixed deciduous and evergreen forests peppered with dogwood in full, white bloom surrounded us for 75 miles. The occasional homestead, from hardscrabble trailers to southern style McMansions complete with faux Doric columns in tacky tribute to antebellum styles, punctuated the roadside. All, no matter how modest, were surrounded by expansive, unfenced turf, where the state’s favorite pastime, lawnmowing on a riding mower, occupied most homeowners, I suspect, at least twice a week; the state’s yearly rainfall averages 56 inches. One particular mower doing double duty caught our eyes. It carried a father and a baby swaddled against his chest, fast asleep from the vibrations of the motor.

That roadside pageant exuded Southern values — hospitality (everyone we encountered stopped to chat, some interminably so, or invited us in for coffee or a Dr. Pepper), individuality and creative ingenuity (the mailbox of a decrepit mobile home hung from a basic folding walker, bailing wired to the outside of one of its armrests in a queer, ungainly tableau lacking any sense of artistry or proportion), and freedom (expensive showcase homes with sculpted topiary as often as not neighbored by battered singlewides with old tires on their roofs holding them down against big blows, surrounded by never-to-be-discarded, one-of-a-kind treasures that seemed left over from some long-past yard sale dating back to the Carter administration, rusty car bodies encircled by still-useful components such as transmissions and U-joints, old water heaters, almost certainly useful for something, chipped pink flamingos and other battered yard art, congealed cement sacks and assorted junk, all of it hinting at the belief that residential zoning is an infringement on liberty).

Nearly all homes lacked fences. At the latter residences — and at some of the former — bored, untethered dogs sprinted out of their yards to give us chase. While all barked up a storm, few actually attacked, and even those that did responded to a firm NO or a tasty treat. One friendly pit bull, Buster, wanted to join our trip and followed us for over a mile. Tina finally stopped at a house to see if the inhabitants knew Buster and could notify his owner to arrange for his return. Of course they did and could, and invited Tina in for coffee. Unfortunately, our sympathy was also elicited by chained dogs — probably neglected — in a frenzy at seeing us. While the finer homes sported welcome signs, the more modest digs warned against trespassing, one additionally declaring, “No stupid people” and another succinctly stating, “No nothing.”

According to Philip Younger, an escaped Alabama “passenger” who made it to Canada and settled in Ontario, “escape from Alabama is almost impossible — if a man escapes, it is by the skin of his teeth.”

We found lodgings in Monroeville at the Mockingbird Inn & Suites; the town was home to Harper Lee, author of To Kill a Mockingbird. While some might decry the crass commercialism in the use of the name of a treasured national icon, we appreciated its enlistment in the pursuit of profit, a necessary ingredient to making a living. (We were more drawn to the motel’s clean and inviting atmosphere than its punnish name.). Lee was a childhood buddy of Truman Capote, another resident of Monroeville.

On to Demopolis! It was a gorgeous Easter Sunday and, by some coincidence, the density of churches seemed to have increased. At one rural crossroads, three churches vied for congregants. Vigorous singing rang out from one, while across the street cars full of worshipers arrayed in a semicircle surrounded a black pastor on an elevated, outdoor pulpit. The third church, a modest rectangular clapboard building, was empty. A plaque in front announced it had been built in 1843. Most churches were Baptist of one sort or another.

“He is risen!” little white crosses declared on many front lawns. He must have awakened in a good, even playful mood, I thought, as he’d vouchsafed us a fun and scenic day that finally warmed up to seasonal temperatures. Instead of the ubiquitous “Have a nice day,” “Blessings,” or some variant of it was common. And it was here that we first encountered the phenomenon of dry counties, either in full or on Sundays, or “damp” ones (only beer is sold). Didn’t Jesus drink wine? I almost asked one lodging host who inquired what we did for church on Sundays when we wanted to know where the nearest liquor store was (outside the town limits). Since we’d made a connection through similar political inclinations, I said that we were atheists and didn’t go to church. After a warm and friendly exchange, he looked at me and said, “I can see there is faith inside you.”

I may lack the faith the innkeeper saw in me, but some folks in the South exude it. Before our ride was over, we saw two reenactments of the Cross Walk, or Via Dolorosa, individuals lugging full-sized crucifixion crosses along public roadways. One penitent was kitted up for a long trek. The base of his cross had two pneumatic tired wheels joined by an axle. He and his companion — not carrying a cross — wore day-glow traffic warning vests, while a pilot vehicle added an additional layer of determination.

While the finer homes sported welcome signs, the more modest digs warned against trespassing, one additionally declaring, “No stupid people” and another succinctly stating, “No nothing.”

The South is different. What little traffic we encountered along these rural roads was invariably deafening, albeit always polite. After all, this is the home of NASCAR and if you can’t go extra fast, at least go extra loud. After many miles I came to realize that churches far outnumber muffler shops and liquor stores combined. After passing a Confederate cemetery and the site of a War of 1812 battlefield, we came upon a sign that must have warmed the hearts of southern Americans with Disabilities Act advocates. It announced the location of a state hunting preserve for the disabled. We didn’t stop to investigate whether there were paved wheelchair trails or braille signs indicating the presence of turkey or deer.

We were surprised by the number of Mexican restaurants we encountered in the deep South, all of them serving delicious food and staffed by real Mexicans, one even from an indigenous tribe in Oaxaca. But I hesitated at eating at “La Gran Acienda.” Yes, Acienda. Misspellings in Spanish are as rare as typos in Liberty. But it was the only attractive game in town, so we ate there. After dinner I told the manager — as gringo-looking as any Alabaman — that hacienda was misspelled. He was from Mexico City and owned the restaurant. He explained that the novel spelling was his sensitivity to the local lingo. In Spanish, the H is silent, a trivial fact little known in Alabama . . . or so he surmised.

On the way to Livingston, extra long — and extra fast — logging trucks became our constant companions, going one way full and the other way empty. They appeared as an obnoxious surprise. We had no idea that the South is the largest timber producing region in the country, accounting for nearly 62% of all US timber harvested. Livingston, adjacent to Interstate 20, provided us with a welcome change from the grits and hush puppy café fare we’d been eating. While East Indians seem to be taking over the hotel and motel industry, they are also becoming big rig truckers and investors in truck stops. This Interstate exchange boasted an Indian restaurant, although with covid, it was open only for takeout.

While waiting for our order, I engaged a trucker whose English was rough; he was waiting for his order too. Serendipitous encounters while traveling are at the heart of slow journeys. We spoke in Spanish. The man was an ex-Nicaraguan now living in Houston under political asylum. He’d fought as a Contra between the ages of 14 and 19. Five years is a long time — a third of one’s life — when one is only 15. He ran a regular route between Houston and New York, always stopping here for the curried lentils . . . though in general he did not care for Indian food. He’d traveled to Cuba illegally in 2014, was discovered by US authorities on his return, and was detained and questioned on suspicion of being a double agent. He’d only gone to Varadero, Cuba’s elite foreign tourist beach resort, on vacation. His daughter serves in the US Army.

After all, this is the home of NASCAR and if you can’t go extra fast, at least go extra loud.

It rained that night, and the following day dawned overcast. It started out with a full roll of pennies lying by the side of the road. Finding money on the ground is always an omen of a good day, but the rain had decomposed the paper roll, forcing me to painstakingly penny pinch each one individually, a delay that irritated Tina. Midmorning, a pickup truck stopped to chat. The driver knew exactly what we were up to. He said he was a “Warm Showers” host but due to covid, hadn’t put anyone up for a while. Warm Showers is a nonprofit hospitality exchange service for people engaged in bicycle touring.

We stopped for lunch at the tiny hamlet of Gainesville. At its entrance stands a modest monument commemorating the spot where Confederate Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forest surrendered on April 9,1865 and delivered his farewell address to his men. The modest country store had little to offer in the way of lunch other than Moon Pies, Little Debbies, and Yoohoos, which all came to $3.17. So I put down three one-dollar bills and carefully counted out 17 cents from the roll I’d found earlier, and declared triumphantly to the proprietor, an old backcountry black lady, “Pennies on the dollar!” When she didn’t react to my pathetic pun, I was totally deflated. So by way of explanation, I told her about the roll of pennies I’d found earlier (it’s doubly pathetic to explain a pun). She remained blankly impassive. On the way out of town we passed a Confederate cemetery with 250 graves from the Battle of Shiloh.

Mississippi

We crossed over into Mississippi (Birthplace of America’s Music) and reached Columbus, a beautiful small city of 24,000 residents, but over 600 historic properties, many of which are antebellum homes, with 23 of them on the National Register of Historic Places and quite a few open for tours. We passed by one, Camellia Place, built in 1847, with a For Sale sign now. Priced at $399,000, in excellent condition, on 1.6 acres, with modern utilities, (mostly) original furniture, 6,000 sq. ft., 5 bedrooms and 4 baths — it was a bargain. We decided to take a layover day and tour the sights.

One mansion’s basement had been turned into a Confederate hospital (though it took in Union soldiers also) after the Battle of Shiloh. The owner had recently found a poignant artifact: a Minie ball, doubtless removed out of a combatant’s body. Another host, Sid Carradine, of the Amzi Love Home (1848), greeted us dressed in period costume along with the Stainless Banner flag, the Confederacy’s second national flag (and not to be confused with the Stars and Bars, the flag from 1861–1863 flying from the porch. He decried the fact that the Stainless Banner flag had been appropriated by bigoted rednecks. Amzi Love was no mansion; it was the town “cottage” for the plantation owners. Sid is the seventh generation of his family to live in the house (and he’s no spring rooster, though he averred that as a young man he’d dated Cybill Shepherd).

Although UGR activity in Alabama and Mississippi was relatively low, Dr. Alexander Milton Ross, a Canadian botanist and UGR conductor, toured the Deep South between 1855 and 1860 spreading the UGR’s message of freedom and recruiting passengers. While in Columbus under the guise of doing ornithological research, he was assigned a slave guide by a hospitable but “coarse and brutal” plantation owner. Ross convinced the slave, Joe, to take the UGR to Canada. But the plans went awry. Joe insisted on taking his brother, who worked at a plantation eight miles distant. Ross provided Joe with detailed instructions and names of conductors in Ohio and Indiana, along with a pistol, a knife, a $20 gold piece, and a pocket compass. When Joe failed to show up for work on Monday, Ross — already under suspicion for abolitionist views — was arrested for “having enticed away his nigger Joe.”

As a possible sentence of death was about to be passed on Ross, Joe dramatically entered the court room and explained that he’d gone to visit his brother on his days off but sprained his ankle while returning, thereby being delayed. Ross, claiming great inconvenience due to his accusation, requested as compensation that the plantation owner agree not to punish Joe — a request that was granted. A week later, Joe and his brother escaped. With the provisions and information Ross had provided, and a stash of food the brother had secreted, the pair were able to reach the Ohio River in seventeen days, a phenomenally short time. After reaching Ontario, Joe made his way to Boston, where he became a waiter at the American Hotel, while his brother remained in Canada.

Not all escapes from slavery involved such travails and subterfuge. Reuben Saunders and his master (Saunders being his only slave) rafted and warehoused cypress timber on the Mississippi River, a lucrative pursuit at the time. After 16 years, the master bought Saunders’ wife, his three children, and his wife’s brother with the fortune he’d accumulated. He then took them to Indiana and set them free. As Saunders recounts, “My family cost him $1,300 [about $45,000 today]. He afterward went down the Mississippi with eight hundred dollars, and to sell some land and wind up. He was lost off the boat and drowned; some thought he was robbed and pushed overboard.”

Many plantation owners were loath to pay their ex-slaves a wage at the recommended level. They consequently failed to retain a labor force, couldn’t pay their property taxes, and lost their farms.

After the Civil War and the freeing of the slaves, many of the plantations in the area found it difficult to adapt to the new dispensation. To help both the freedmen and the plantations, the Freedmen’s Bureau recommended a wage level that would allow both parties to survive and rebuild the economy. Many plantation owners were loath to pay their ex-slaves a wage at the recommended level. They consequently failed to retain a labor force, couldn’t pay their property taxes, and lost their farms. Sid’s ancestors’ plantation, which did adopt the Bureau’s suggested wage, was one of the few in the area that retained its workforce and survived.

We were now edging north into Civil War territory, having already passed Nathan Bedford Forrest’s surrender site and two Confederate cemeteries. Columbus’ cemetery held both Confederate and Union dead, acquiring the name of Friendship Cemetery. On April 25, 1866, a large group of ladies from Columbus decorated the graves of these fallen soldiers, from both sides, with flowers. The women’s tribute — treating the soldiers as equals — inspired Francis Miles Finch to write the poem The Blue and the Gray, which was published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1867. However, in that same year — probably in a fit of pique — the remains of all Union soldiers (only about 100 out of 2000) were exhumed and reinterred in Corinth National Cemetery. Eventually, the ”grave decoration days” begun by the southern women honoring those who died in military service morphed into Memorial Day.

The last home we visited was the birthplace of Tennessee Williams. Built in 1875 and of modest proportions, it had one small room repurposed as Columbus’ tourist office; the rest was open for touring. On our last day, Sid bought us breakfast at Columbus’ most popular greasy spoon.

Again, I stood out as virtually the only white person in the store . . . and a stranger in shorts at that.

After another tornado warning, we rode on to Aberdeen, home of Booker “Bukka” White, Chester “Howlin’ Wolf” Burnett, and Albert King, three of the most influential blues artists, and next door to Tupelo, Elvis Presley’s hometown. Though it has only a population of 5,600, Aberdeen boasts over 200 places on the National Historic Register, many of them antebellum mansions lining the street along which we entered.

Staying at Three Goats Cottage, we had a fully furnished kitchen, so I decided to cook at home. I bought groceries at the Piggly Wiggly. Again, I stood out as virtually the only white person in the store . . . and a stranger in shorts at that. The staff and locals uninhibitedly stared at me, smiling and asking where I was from, where I was going, what was I doing in Aberdeen. All were very southern — some unintelligibly so — friendly, rural, and with none of the trappings of the “hood.” One bagboy insisted on carrying my groceries out the door, even though I had only one bag and was on foot. He lingered outside with me and provided the sort of chit-chatty, obvious advice meant only to prolong our contact.

Our last stop in Mississippi was Iuka, site of a notable Civil War battle, a battle that was part of the Union’s strategy of capturing the Memphis, Nashville, and Corinth area, where railroads and rivers intersected to provide the Confederacy with essential transports and communications in the western theatre. We were traveling north, in the opposite direction of the Union’s advance. I was carrying and reading the first volume of Shelby Foote’s The Civil War: A Narrative (at three pounds, Tina thought I was daft). Foote’s clear and engaging prose, with in-depth character sketches and political context, allowed us to make sense out of the geography we were passing and about to pass, albeit backwards.

I hope, if you ever come that way, you don’t stay where we did, even if it’s your only option.

In a nutshell, the campaign began in Kentucky with General Grant’s capture of Paducah — which began his meteoric rise — followed by his capture of the confluences of the nearby Ohio, Tennessee, and Cumberland Rivers. These victories tilted neutral Kentucky towards the Union. He then moved south into Tennessee and captured Confederate Forts Henry and Donelson, one on each river, which at this point were only six miles apart. Grant then advanced his armies to capture Corinth, but was stopped at Shiloh by Confederate forces meant to destroy him. Yet he prevailed, opening the door to the capture of Corinth, decisively securing Kentucky for the Union, capturing western Tennessee, and opening the riverine road to Vicksburg.

I hope, if you ever come that way, you don’t stay where we did, even if it’s your only option, which it was for us. The missing M on our motel’s logo was only a hint. Inside, the abandoned grocery cart surrounded by garbage in the reception area and the dead cockroach in the key-and-cash slide under the barrier separating the client from the manager were enough to make us consider sleeping rough. The East Indian owner was friendly and bent over backwards to be accommodating, but our room was barely furnished and devoid of decorations, the bathroom’s wall had a large hole with the insulation billowing out, and the toilet had bits of used toilet paper stuck to the seat. Tina asked for clean sheets, which the owner immediately produced and offered to install. She demurred. He explained that he painstakingly sanitized the rooms each day. Tina wasn’t convinced. Next door lowlifes squatted outside, vaping and smoking. The owner’s wife, resplendent in a full sari and garish jewelry, marched up to them and requested something or other. The drug addicts were so out of it that our only worries were roaches crawling over us. We were exhausted but slept fully clothed. I suggested taking a sleeping pill in order to at least rest well. I did, but Tina, ever worried that a cockroach would find her face, hardly slept. It was the trip’s low point.

Tennessee

On April 14 we crossed into Tennessee and entered Shiloh National Military Park via its back road. It was as if we’d entered a Zen garden dedicated to the victims of a holocaust . . . which in a sense it was. Its 5,000 acres are meticulously landscaped with mowed lawns and both wild and manicured forests. The park is strewn with original rifled and smooth-bore ordnance located in approximately (as if with an eye to feng shui) original locations, interspersed with granite monuments to regiments, corps, militias, and armies, along with commemorative obelisks to individual and group casualties. There are no barriers or “NO” signs; everything is accessible . . . to touch, see, sense and absorb what one stela means when it says, “There is no holier spot of ground than where defeated valor lies.” Shiloh has no entrance fee. We saw no roving rangers. There were few visitors. The interpretive movie in the visitors’ center is second to none.

Grant had come up the Tennessee River on Navy boats for his advance toward Corinth, the strategic cross-Confederacy hub of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. He disembarked at Shiloh’s Pittsburgh Landing (only 22 overland miles from Corinth) to await General Don Carlos Buell’s Army overland arrival. Together they would march upon and take the city. However, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston seized the initiative and attacked Grant before Buell joined him. Grant was cornered. Behind him, the Tennessee River, with swampy Snake Creek debouching at a right angle, prevented any sort of retreat. Grant had 40,000 men; Johnston attacked with 44,000. And while defenders usually need at least one-third more strength than their attackers, Grant didn’t even have time to dig effective entrenchments for a proper defense. The first day of the battle, Johnston nearly overran the Union forces, pushing them back two miles, right up against the river and swamp. But the Union soldiers stubbornly contested the onslaught. Late in the day, when General Johnston was mortally wounded, Confederate spirits sagged.

The unprecedented carnage was appalling. Calls for Grant’s removal grew apace. Newspapers called him a butcher.

General P.G.T. Beauregard took over. By morning, he was certain of victory. But Buell arrived that night with 20,000 Federal reinforcements, allowing Grant to counterattack in the morning. For six hours the outnumbered Confederates resisted, until they no longer could. Beauregard ordered a retreat to Corinth. The battered Federals did not pursue.

Shiloh’s 23,746 casualties outnumbered the combined casualties of all the previous North American wars: the French and Indian War, the War for Independence, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War. And it was still early in the Civil War — April 6,1862. Shiloh is considered a decisive Union victory — a conclusion reached only after evaluation in the light of subsequent events. It cheered some, but the unprecedented carnage was appalling. Calls for Grant’s removal grew apace. Newspapers called him a butcher. President Lincoln resisted, saying that “this man” Grant — unlike other generals — “fights.” But when the political heat got too strong, Lincoln referred the matter to General Henry Halleck, overall commander of the Union’s western theatre. Caught between politics and effective military leadership — Halleck appreciated Grant’s abilities — he promoted him out of command and made him his own aide-de-camp.

Halleck needed Grant, especially now that it fell to Halleck, as the field commander who had inherited Grant’s regiments, to capture Corinth. Although he had written the definitive volume on military strategy and tactics, Halleck had never been in combat. The man was an extremely cautious commander, and more so after the slaughter at Shiloh. He determined to minimize casualties during the Corinth campaign, particularly since reports indicated that Confederate forces in Corinth numbered 200,000 (in fact, they only numbered 45,440; while Halleck’s combined forces were more than 120,000).

Halleck advanced slowly and cautiously. Foote reports that Halleck would advance half a mile a day, “burrowing as he went. An energetic inchworm could have made better time.” Advance in the morning, entrench in the afternoon, sleep at night, repeat the next day. The troops hated it . . . and it wasn’t Grant’s kind of war. But after moving only five miles in one three-week period, Halleck’s artillery was finally in position to lay siege to the town. And it worked. On May 29, 1862 after the Union’s monthlong advance, a siege and assorted skirmishes, Beauregard evacuated Corinth.

No longer would the slaves attached to Union troops be referred to as “contraband,” especially after the Emancipation Proclamation.

The fall of Corinth wasn’t just a major tactical victory; it became the realization of the Underground Railroad’s objective: freedom for the slaves . . . at least in Tennessee, northern Mississippi and Alabama, and nearby areas. Thousands poured into town seeking the protection of Federal troops. Union General Grenville Dodge established a tent city northeast of town, which soon blossomed into a thriving community of 6,000, including homes, a school, a church, a hospital and a cooperative farm program. No longer would the slaves attached to Union troops be referred to as “contraband,” especially after the Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863). Following the war, Beauregard returned home to Louisiana, where he became an advocate for black civil rights and full suffrage.

Forget Facebook and its ilk. Highway truck stops are America’s real social entrepots. We bought breakfast at one in Crump. Inside, a 20-something man in jeans, T-shirt and baseball cap engaged us. His pickup was full of self-reliant stuff, an assortment usually associated with a jack-of-all-trades. He envied our trip. When we countered up to pay, the attendant said the man had bought us breakfast. Later that day, crossing Interstate 40, we stopped for lunch at a Pilot Truck Center. Queuing at Arby’s, we observed the two men ahead of us, one black one white, tête à tête, one rubbernecking to the overhead menu and back to his companion. I caught the distinctive cadence and elisions of Cuban Spanish. Amazed at the unlikely encounter, and even more at the apparent language difficulty — after all, Cubans aren’t recent arrivals, master English relatively quickly and . . . in central Tennessee? — I approached them. They were long-haul truck drivers. One, the one whose English was deficient, had broken down, the other had come to help him. They had left Cuba in 1999 and 2000, respectively. I wished them well.

That night, outside tiny Waverly, our reluctance to eat catfish crumbled. Eating bottom feeders? Not for us. Surprisingly, so far during our ride catfish restaurants outnumbered steak houses. But Little Josh’s Family Diner was the only game in, or out, of town for eats. It was closed for indoor dining, and the parking lot was full of vehicles awaiting take-out orders. Yet it was a great find. While waiting outside for our orders, we saw an employee walk out the back door to an adjacent building and return with a platter full of fresh fillets. We strolled over to the adjunct to investigate. Five galvanized water troughs full of circulating and aerated water teeming with fish buzzed in the twilight. Little Josh’s grew their own, healthy-fed fish. Our dinner, accompanied by hush puppies, deserved at least one Michelin star.

Dover, adjacent to the Kentucky state line, would be our last stop in Dixie. Where else can you get a bologna sandwich on white bread, with mayo, at a conventional fast-food outlet? Meet a girl with a Bible tattoo on her arm — not a full verse, mind you, just the chapter and verse numbers? Where smoking cigarettes is ubiquitous and not the mark of Satan? Where obesity rates hover at 40%? Where cars stop in the middle of the road just to chat? Where underbites, perhaps a physical manifestation of Southerners’ don’t tread on me attitude, are as frequent as front porch US flags? Where taxidermy is still a common and profitable profession? Where boiled peanuts, either fresh or canned, are available at every convenience store? Where pork, in all its permutations — pulled, BBQed, fried, roasted, cured, sausaged, bolognaed, head cheesed, smoked, jerked, gravied, and Boudined — isn’t just for special occasions, but is suitable as everyday fare for breakfast, dinner, supper, and snacks?

Al Capone made his last run — taking a 60% cut — at Hudson’s still, one of his regular suppliers.

We stayed at the Dover Inn Cabins, recently under new, foreign-born owners. Nikki and her brother Kumar were born in Gujarat, India. One day their parents declared, “We’re moving to the US!”

“Why?” The 13- and 11-year-olds asked.

“To seek the American Dream!”

The family landed in Chicago but soon moved to Springfield, Illinois, where Nikki and Kumar attended school and learned English. After 9/11, the other kids hassled and bullied them as the perpetrators of the atrocity. They took it in stride. When the family bought the Dover Inn and then the gas station across the street (only one of two in the town), the locals reacted, “The Indians are taking over!” But Nikki and Kumar took no guff, and when they showed that they wouldn’t, they fitted right in, particularly because Nikki manages the gas station from 5 AM to 5 PM, and the inn from 5 PM to 5 AM. Kumar is an AI whiz in St. Louis, but spells Nikki periodically. Both speak unaccented English and reject arranged marriages.

Mike Hudson, the Dover Inn’s handyman, has worked there for 28 years. He said that his grandfather ran a still just behind the cabins (Dover is still dry, though two nice ladies each offered us a bottle of wine) and that Al Capone made his last run — taking a 60% cut — at Hudson’s still, one of his regular suppliers. Capone was nabbed soon thereafter. We laid over two days to rest, avoid bad weather and visit Fort Donelson National Battlefield.

Forts Henry and Donelson were paired Confederate strongholds. While Fort Henry fell quickly, Donelson took longer to subjugate. It was here that Grant got his nickname, Unconditional Surrender Grant, after he refused to accept the terms offered by Donelson’s commander: “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.” February 1862 — it was the Union’s first major victory and is considered by some modern scholars the turning point of the Civil War, where the eventual outcome of the war became inevitable.

Thomas Carlyle expressed his impatience with the Civil War, in which people were “cutting each other’s throats, because one half of them prefer hiring their servants for life, and the other by the hour.” On first glance, his statement seems to ignore the “servants’” choice in the matter. On closer analysis, those words say a lot about the customs of the times. Despite the Industrial Revolution, most people lived a hardscrabble, rural existence, with few choices. Even those who moved to cities and took jobs in industry, took what they could get.

Dawn temps were below freezing. We weren’t clothed for that, so we headed to the dollar store to buy gloves and donned every bit of clothing we possessed.

It’s an interesting perspective. At the time of secession, both Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, and Alexander Stephens, vice president, argued that slavery was the reason for the conflict between North and South. However, in their subsequent memoirs, both reflected that the war had been about states’ rights. In the North, Lincoln believed that he couldn’t muster an army to free the slaves, only to preserve the Union. Northern states saw the secessionists as traitors. Other than avowed abolitionists — the “radical Republicans” — Northerners didn’t much care about the slaves. As the war progressed, sentiments evolved. The causes, both ultimate and immediate, of our Civil War will never cease to be debated.

Kentucky

Today, the first 40 of the 50 miles between Dover and Grand Rivers, Kentucky are a unique National Park, the Land Between the Lakes. Both the Tennessee and the Cumberland rivers have been dammed just before their confluence with the Ohio. For the entire distance, less than ten miles separate the lakes that resulted.

We woke up early to cover the up-and-down ride, which straddles the ridge between the lakes, but the passing storms had bred a vicious cold front. Dawn temps were below freezing. We weren’t clothed for that, expecting late April temps in the deep South. So we headed to the dollar store to buy gloves and donned every bit of clothing we possessed, including baseball caps under helmets and rain parkas.

The LBL, as it’s known, is a special place. Before the Civil War it was populated by single and extended family farms. With both rivers so close, their cottage industries could be easily shipped to markets. Though slavery was legal, it wasn’t prominent. Most of the LBL farms either lacked slaves or, at the most, might have one, who was usually treated as a member of the family. Numberless family cemeteries, all reverently signed, dotted our route and attested to the presence of many homesteads.

The jewel in the LBL’s crown (besides its bison herds) is the Homeplace, an 1850s living history farm and museum. Many period reconstructions tend toward the cheesy, but the Homeplace is different: all the buildings are original and located on one old farm, although some have been moved from other old homesteads to combine the various 1850s farm specialties — tobacco, pigs, sheep, weaving, meat curing, tanning, etc. Additionally, it’s staffed by working craftspeople — blacksmith, weaver, plow team, etc. — in period attire.

“Did you hear the news today?” The baker reenactor asked us after we got to talking with her. “Our budget got cut from 1.8 million to zero!”

We were taken aback, especially since the Trump administration had recently passed the Great American Outdoors Act, which provided $11.6 billion for deferred maintenance in national parks. Was this a case of Trump proposes, Biden disposes? Mitch McConnell, one of Kentucky’s senators, was furious. So far — at the time — the reduction seemed to be an administrative mistake that the concerned parties scrambled to rectify.

On April 23 we hit the Ohio River. Free at last! Or so escaped slaves might have thought as they breathed a sigh of relief at leaving slaveholding America . . . once across. Few could swim, and few good swimmers could swim that river, anyway. The escapees depended on a complex series of signals between the riverbanks, usually following a standard protocol at predetermined locations, for an abolitionist’s ride over to Illinois. The Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio routes to Kentucky, according to Blockson, “probably served more fugitives than any others in the North.” And we hit the river along an area that Blockson describes as one where more crossed over the Ohio River than at any other along the Ohio.

The following morning dawned cold, rainy, and windy. The predicted high was 40 degrees, with constant, heavy rain driven by a gale-force north wind.

Between Grand Rivers and Henderson along the Ohio River, about 120 miles, towns are few and services fewer. Our only lodging option, a reasonable distance away from Grand Rivers, where we were located, was Cave in Rock State Park, across the Ohio in Illinois, where a handful of rental cabins were available. The map did not show a bridge across the river, but we discovered a ferry. The cabins were on a bluff overlooking the majestic river. We shared a bottle of wine on the porch and watched the occasional tug push an ungainly line of barges full of coal through the thickening misty fog.

It was a bad omen. No, not for climate change — for us. The following morning dawned cold, rainy, and windy. The predicted high was 40 degrees, with constant, heavy rain driven by a gale-force north wind. We asked to stay another night, until the storm blew over, but the cabins were booked solid. The manager called everyone who had a reservation to ask if he wanted to cancel because of the weather. No one did. Our web search indicated that the next closest lodging was in Harrison, Kentucky, 50 miles away — an impossible distance on bikes in those conditions, especially with the clothing and “protective” gear (sun shirts, shorts, and light rain ponchos) we carried for a late spring jaunt in the South.

But here was where local knowledge came to the rescue. The manager knew of some hunters’ cabins in tiny Sturgis, only 23 miles away, cabins that did not appear on an internet search. She called the owner. Yes, he’d take care of us. Very reluctantly we donned every bit of kit we owned and set out.

It wasn’t long before we were both soaking wet. Under the protective roof of an abandoned gas station Tina stopped to check her Google maps app and stow her phone away, its protective shield failing miserably in these conditions. I told her to forget Google, I knew the way, and that our best strategy was to get to Sturgis as fast as possible: “I’m not going to last long in these conditions.” We set off as fast as we could pedal.

We must have looked a wreck. The manager in Sturgis gave us his best cabin but charged only a pittance. He’d already turned up all the space heaters inside. We stripped and jumped into hot showers until the hot water ran out.

I told her to forget Google, I knew the way, and that our best strategy was to get there as fast as possible: “I’m not going to last long in these conditions.”

Our last day dawned clear and chilly. The 27 miles to Harrison were flat and pleasant. Though our destination had been Owensboro, we found out that not a single rental car was available there. Apparently, there was a nation-wide rental car shortage, and we needed one to get back to our van in Mobile. But right across the street from the Hampton Inn that we were staying at, Enterprise had one vehicle available.

And so concludes this wandering narrative, not with a bang but a leisurely two-day drive along America’s arteries — its interstates — instead of its tiny capillaries, the rural byways where fun, adventure, undiscovered history, and lucky serendipity await.

For those interested in the less known Underground Railroad to Mexico, refer to South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War, 2020 by Alice L Baumgartner

Once again Bob Miller leaves us with provocative glimpses of some politically-incorrect politics, viewed through the metaphor of outdoor adventure and exploration and salted with the ephemeral truths of history.