So I’m in the chair at a Fox News studio on Friday night, getting my makeup put on. It’s funny that I can almost predict where the cover stick is going to be applied. After many long years of staring at myself in the mirror, I seem to know where all the major flaws are. I’m sure if I were a woman, this would almost be a second nature, but I don’t often get makeup put on.

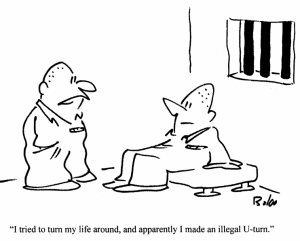

I have been a stand-up comic for three-fifths of my life. July 4, 2009 will be the 30th anniversary of my first time on stage. It’s not been an easy road, and I swear I can see every cocktail, every 24-hour drive, and a couple of kited checks in the lines on my face right now.

I am a comic. It’s what I do, and until Liberty asked me to do this article, I never really considered that unusual or unique. Occasionally I’m reminded that it is.

“You should come to my job.” That’s the most common refrain a comic hears as the audience leaves the room. Everybody thinks there is something or someone at work that has the potential for comedic greatness, “We crack up all the time – there’s this guy …” Sometimes an audience is a little less forgiving. “I could do what you do” one guy tells me. You probably could. It’s fairly easy. Standing in front of people and getting them to laugh isn’t that hard. In fact, it’s kind of fun. The hardest part is finding someone to pay you for it.

I got into comedy in the late ’70s. I remember reading an article about a guy who painted chewing tobacco ads on the sides of barns. I think he was probably the last person on earth still doing that job, even way back then. But he said something that has stuck with me through all the awful gigs I’ve ever done. He said, “First find something you really enjoy doing; then all you have too do is find someone fool enough to pay you for it.”

“Your makeup’s done,” the girl said. I’m going on “Red Eye,” a late-night Fox News comedy show with Greg Gutfeld. Greg, his co-host Bill Graham, a talking newspaper puppet named “Pinch,” and a couple of guests, at least one of whom is always a beautiful woman, skewer the stories of the day. I really get a kick out of Greg. He claims to be a conservative, for the sake of contrarianism, but there is a thick libertarian streak down his back.

As I sit on the barstool in front of the camera, I’m informed that the monitor isn’t working. It realized my biggest fear – not being able to watch the show I’m appearing on. When I agreed to do this, friends who have worked the 24-hour news format before told me that quite often there is no monitor. It might be easy when it’s a one-on-one interview, but in a madhouse like “Red Eye” with five people and a puppet trying to wedge in jokes, following the action over an earphone is going to be rough.

I do my best to be funny, and make it look like I’m not struggling. The topic finally works around to Janeane Garafalo, who had claimed the day before that the only reason anyone could oppose the president is because they don’t

It seems that no matter how early I fly, by the time I get into the hotel there is little time left for anything other than taking a nap before the show.

like a black man in the White House. She claimed that tax protestors are nothing more than “tea-bagging rednecks.” I have a great rebuttal rant worked out:

“Janeane Garafalo is as familiar with right-wingers as she is with a razor … If it were not for the right-wing producers of ’24,’ right now she would be opening for Marc Maron at Bananas Chucklehut in Ottumwa, Iowa. She wouldn’t talk like this if there were a chance at a second season, so you know her character on ’24’ is only going to live about 23 hours, which is about two hours longer than her talk-radio career….”

Gutfeld cuts me off after “razor.” Dang. I thought I had botched the interview, but later people who watched it told me it went quite well. Not much time to dwell on the show, since I’m working in Minnesota the next week. I shouldn’t even have been doing the show, since I was scheduled to be in Fargo, North Dakota that weekend.

Unfortunately, as it does every spring, rain came to North Dakota about the same time the ice and snow were melting, and the place where I was supposed to be telling jokes that evening was submerged. The adage is, the show must go on; but, strangely, quite often it doesn’t. So when I got the call for “Red Eye,” I was more than available.

But l love doing stand-up. My life sometimes seems just an uncomfortable nuisance that goes on between those short minutes when I’m under the lights and have a mike in my hand.

Comedy is closer to an addiction than a career. The comics I’ve known all suffer some of the same symptoms as other addicts: voluntary poverty, broken homes, and codependency. You11 often find them living in dumpy apartments with several other addicts, or driving to a questionable neighborhood in the middle of the night just to get a gig. There is also cross-addiction. Almost every comic I know has another habit that is probably just as severe. When I think of the fattest people I have ever met, they were all comedians. Ditto for drunks, junkies, nymphomaniacs, and gamblers.

I got into comedy because I had always been fascinated by the art form. The idea of just getting up and talking is part beatnik poet, part rock’n’ roll. Why wouldn’t such an idea appeal to a kid like me, who spent his youth bouncing between jobs and schools, never really finding a place that could hold his attention for more than a month at a time.

Tuesday I’m running late to the first show of the week in Minneapolis. I am headlining all this week at Acme Comedy Company. Opening nights are always tough. It’s a travel day, and I’m always jet lagged. It seems that no matter how early I fly, by the time I get into the hotel there is little time left for anything other than taking a nap before the show. The preshow nap is something almost every comic does. It’s considered a perk. The reasoning is, you want to be up and excited for the audience. If you don’t seem happy, it’s really hard to make the crowd happy. You want to present the same freshness that people normally have when they arrive at work, showered and shaved and ready to go.

So if a comic doesn’t intend to sleep right up until showtime (some actually do – I’ve met a couple guys who stay up till late morning before they go to bed), for those of us who enjoy regular hours taking a nap is usually the only way we can get any normal daylight. We are like vampires among the living.

Sometimes we even have the same anonymity as vampires. I think comedians guard their professional identification as tightly as sewer workers and hedge-fund managers. When the inevitable small talk circles around to jobs, I stammer and stutter, trying to avoid the question. “I work in a bar” is usually the best response.

Everybody loves to hear a good joke. Once your profession is revealed, people expect you to launch into a routine for them. In the realm of “people who are expected to provide free services for strangers,” I think we nose out even doctors and lawyers. I guess I should approach it more as they would,

In the realm of “people who are expected to provide free services for strangers,” I think comedians nose out even doctors and lawyers.

handing out a card and saying “call my office and make an appointment.” Despite my love for the craft, I’m not always ready to punch the time clock and go to work in the middle of an airport. People don’t realize that. Telling jokes may be fun, but it is still my job.

That is probably the fault of comedians. The illusion of comedy is that you’re having a really good time on stage, and life is just a big party. I doubt many people recognize the effort it takes to do a routine with all that enthusiasm, acting as if you had just thought of all these wonderfully clever things you spout on stage.

The club audience has been up all day, and their energy is usually winding down. On weekdays, it’s even worse. Some of these people have been up since 5 a.m. It’s the reason why mostly youngsters populate the weeknight audiences. Once you get much older than 30, staying up late and dragging the whole next day becomes a burden. Bert Haas, the GM of the Zanies comedy chain in Chicago, once put it in words for me. He said that at his age, somebody has to be a very interesting conversationalist to keep him up till three in the morning. He speculated that there were probably only a dozen people in the whole world that could be interesting enough to lose that much sleep over. When he was in his 20s everybody was that interesting.

Up early Wednesday morning for radio. I do an hour for the uChris Baker Show” on KTLK-FM. Morning radio is normally the bane of comics. It’s a great way to get the crowd out to the show, because if people are laughing on the way to work, they might enjoy coming into the club afterwards. A comic who can do good radio will always be rewarded with a great turnout at the door. There is something special about actually seeing someone live that you’ve just heard on the radio.

Unfortunately the times for these morning shows do not work on a comic’s schedule. Comics can’t go to bed right after a show. Usually after a show you’re completely pumped, and there is no way you can just turn it off and go to sleep. I know that a lot of guys don’t eat until after a show, so it’s usually dinner and probably drinks, and a little gabbing till the wee hours. I find it very hard to get to bed before two, and sometimes they want you in the studio as early as six. Most morning radio hosts get up about the same time comics are coming to bed, so the synergy is always off kilter.

This week was an exception. Chris Baker and I hit it off really well. It was Earth Day, and we had a really good time making fun of Al Gore and all the horrible predictions and threats to our economy. The middle act was from Seattle, so naturally he bought into the whole warming scenario. He said this is the first extinction in world history that was caused by a species.

“So what’s the big deal?” I asked him. “Why is an extinction by a meteor acceptable, but one caused by humans is not?”

“Well, the volcano is a natural extinction.”

“So are you saying humans are not part of nature?”

Wednesday evening, Dan Schlissel awakens me from my nap. Dan is my distributor. He produced my CD, uEuropa,” and handles its distribution on Amazon, iTunes, and other outlets. He has some renown in the industry, and actually won a Grammy for producing “Lewis Black, The Carnegie Hall Performance.” He takes me out to a place where they serve coal-fired pizza. Apparently this is the latest fad in pizza, where the ovens are heated with coal. Dan explains that the original pizza ovens in New York all worked that way, and because of grandfathering, only the older pizza joints are still allowed to use it. It is the extremely high temperature that gives New York pizza its trademark crust.

But the ovens in New York are vented. Only the heat is transferred to the pizza in New York (theoretically). In this restaurant, the coal is burned right alongside the pizza, so the pizza acquires a bit of the coal flavor. It also probably acquires the mercury, the sulfur, and a thousand other toxins that make coal the bane of clean energy advocates. But here are Minneapolis residents happily gnawing on vegan pizzas full of blight, beside locally grown organic salads, served by tattooed hippie waitresses. Dan advises me to keep my amusement to myself, lest I chase off all the customers, and the city close his new favorite restaurant as a hazardous waste site.

Dan loves vintage recordings and has an extensive record collection. Not only does he release comedy albums on CD and online as MP3s; he does limited releases of his favorite acts on vinyl. He owns the vinyl rights to Lewis Black, David Cross, and Patton Oswalt. ”A classic comedy album isn’t really a classic unless it’s on vinyl,” he says. “I feel that certain records belong in that category.” Right now he is working on a dream he’s had for years and might finally be coming to fruition: releasing a comedy album on eight-track. His next project will be releasing a four-minute comedy track on an Edison cylinder. (Really.)

The week is going by really fast. Almost before I realize it, it’s Friday night again, and I’m preparing for my weekend shows.

The standard show format is three comics: emcee, middle (or feature), and headliner. The emcee is usually the guy starting out, and most probably a local. Emcee is the entry-level position. The second guy, the feature, is the one who has the material, but he’s still up and coming. He’s expected to do between 20 minutes and a half hour, and it is the easiest job in the lineup. He doesn’t have to warm up the crowd, and he isn’t expected to knock them out and get a standing ovation. Unfortunately, the money isn’t much better than what the emcee makes – maybe enough to pay for a hotel room (if he’s from out of town) and a couple trips to the China Buffet.

Friday evening I take the other two comics out for lunch. It’s a tradition that has been handed down from the early days of the business. The headliner is expected to take the opening acts out for lunch at one point during the week. The only thing expected of the opening act is a promise to buy lunch for his opening acts when he starts headlining. It’s a really neat custom, and even though money has been tight of late, I am happy to pass it on down, and grateful to be closing the show. I loved stand-up from the first time I tried it. (In fact, I probably liked it a whole lot more than the people who saw me perform that first pathetic show.) It seemed like it took

forever for me to write my first ten minutes, which back then could get you a job as an emcee. Sometimes they would even pay you gas money. The ultimate goal of all us young kids was the headline slot. When I started out, there was actually a handful of comics touring the country, making a living.

In those days, before there were clubs devoted entirely to the craft, stand-up comedy was a rare treat on TV (shows like “Mike Douglas” or “Merv Griffin”). But the success of New York Clubs (such as the Improv) and the Comedy Store in Los Angeles was imitated in large cities around the country – Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and so on. In the ’80s, comedy started becoming the fashionable entertainment thing to do, and eventually it was possible to make a living as a feature. Surprisingly, even the emcees were making subsistence. I got into the business at exactly the right time. It was my Ringo Starr moment. Around 1982 I hit the road as a professional comic. There were so many rooms opening up around the country that you could work seven nights a week and live

It was Earth Day, and we had a really good time making fun of Al Gore. The middle act was from Seattle, so naturally he bought into the whole global warming scenario.

on the road. No need to pay rent; you just needed an answering machine plugged in on a private line somewhere so the agents could get hold of you. We were all a flock of gypsies traveling from one town to the next. In the early days of the stand-up circuit, comedy was like rock ‘n’ roll in the ’50s: hopping town-to-town, working with Elvis and Little Richard and Johnny Cash. Any week in comedy, you might be working with a future star: Tim Allen, Jeff Foxworthy, Jay Leno all did the same crummy gigs in the same Holiday Inn lounges that I did. One year, I spent almost 50 weeks straight on the road, before I decided to stop being subhuman.

That’s why I moved to Chicago in 1986. At one time, there were close to 30 weeks of work all within a two-hour drive of the city. I could actually park my car and eat a few meals at a kitchen table, rather than off the passenger seat of the vehicle. Chicago not only brought steady local work, it also brought my first taste of fame. As its reputation as a comedy town grew, cable networks were attracted to the city to film some of the up and coming talent. I was lucky to catch the eye of Showtime and MTV talent coordinators.

But tonight, as I said, I’m in Minneapolis, and the other acts and I are sitting outside the restaurant, and I note that before the smoking ban went into effect, Minneapolis didn’t have a lot of sidewalk cafes. Naturally. In a town where the mercury doesn’t rise above zero for months at a time, spending money on patio furniture seems like an unnecessary expense. Well, now that smokers, who are the bars’ best customers, have been forced outside, patio furniture (and outdoor propane heaters) have become a necessary expense for anyone who still wants to run a dram shop.

It is kind of pleasant to dine al fresco in Minneapolis. But now there’s a move underway to ban smoking on outdoor patios. The antismokers are such children. First they wanted to go into bars where people smoked, so they banned smoking. Everybody else had to step outside to smoke. So now that they’re all alone in the bars, the antismokers want to go outside themselves. Minnesota politics are strange. I had a line I used to do there a lot: “They had a professional wrestler for governor; now it looks like they may have a comedian in the Senate – or Al Franken might win.” It was a great line, and it always worked here. But that’s the problem with political comedy: it has an expiration date. I think it was George Carlin who said the trouble with doing political comedy is that you have to keep throwing out your favorite children.

Back at the hotel, I get an email from a girl named Chloe, a Scottish comic now living in New York. She’s passing through the Twin Cities and was hoping I might help her get on stage to do a couple minutes. Since I’m a big sucker for girls with accents, I happily comply. She’s green, but captivating. (I find it hilarious that a 25-year-old from Scotland is also what I’ve been drinking all week). Most of her stuff is okay, but her last joke has a punch line so vulgar I don’t think I can even come close to translating it into a sentence that could be printed in a family magazine like Liberty. Hearing such profanity from an adorable girl makes me double over, laughing.

Personally, I have a couple new pieces that I’ve been working on. One is a warning against the whole environmental concern about saving the earth for our grandchildren. I mean, come on, does anyone really believe that if we make all these sacrifices, those kids aren’t going to sell all our things and put us in nursing homes? (My grandfather fought in World War II. He really saved the earth, from Nazis and fascists, and the Empire of the Rising Sun. What did he get for his sacrifice? A Filipino nurse who gives him flashbacks of Iwo Jima … ) The bit develops to a huge crescendo, with a pleading old man telling his grandson how he washed and sorted all his garbage into 12 recycling bins for this generation, and all his grandson cares about is getting a vintage Prius with just 15,000 miles on it. I can’t get that bit to work. It just lies there. Maybe it’s too dark, or maybe there isn’t even a joke in it. I can’t tell, because it’s really funny to me. That happens sometimes. Sometimes it’s impossible to find a closing line that wraps up a bit succinctly and generates some applause. No matter how many times I reword it, or change the perspective or the voice of the grandson, it just won’t come out the way I want it to.

I’m also working on another bit. It was inspired by a good friend and longtime libertarian activist, Barb Goushaw. In a bar conversation she once revealed to me that she wanted to pay slavery reparations. It’s an interesting idea, because if we did, the debt of the white man would be paid in full: “no more affirmative action, no more set-asides, and if I want to tell a joke about a black guy going into a bar with a parrot on his shoulder, I won’t have to look both ways before I hit the punchline.” I’m really having a hard time wording that joke so that people don’t get uptight about it. In this modem world, it seems that joking about something as serious as slavery is completely wrong.

But I’ve never been one to shy away from controversy. To me it is the jokes that make people uncomfortable that are the funniest. At a Liberty magazine conference a couple years back, I was teasing David Friedman. He had once told Liberty founder Bill Bradford that he didn’t find anything funny about me. Bill, being one who liked stirring things up from time to time, just had to tell me about it. So I spent the rest of the conference arguing with David over whether I was funny or not. His conclusion was no, that I was more shocking than funny, that I use political incorrectness in the same way that other, lesser comics use profanity, getting laughter out of the crowd’s discomfort. But I certainly wasn’t getting laughter out of it now. I bombed big on the first show Friday. It seemed that slavery jokes are not edgy in Minneapolis; they’re completely off the cliff.

A friend of mine recently speculated why comedy is getting so big: political correctness has taken over America. You can no longer speak your mind in the classroom or at work, for fear of offending another person and possibly facing a lawsuit. The comedy clubs are the last bastion of free speech in America. In 1988, in a case called Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46, the Supreme Court decided that the authors of parody could not be held for libel. This set the ground for the current popularity of comedy clubs. As the workplace and schools began cracking down on “hate speech” throughout the ’90s, the comedy club emerged as the one place where people could say what they thought.

The worst show of the week is always the dreaded Second Show on Friday. It usually starts around 10:30 p.m. Most people in the audience have been up for 15 hours or more, and many have been drinking for the last five. They might be young, but they are also tired, and half in the bag. And they are a little ignorant. Perhaps I’m generalizing, but it isn’t always the Phi Beta Kappas who are out at the bar at 10:30 on a Friday. Usually these people are the same demographic that is courted by 24-hour laundromats. Strangely, tonight the second show seems to appreciate my humor more than the first. Maybe the reparations stuff only appeals to rednecks.

This leads me to wonder, not for the first time: what is the nature of comedy? I remember one of my theater teachers telling me that clowns all have characters based on one of the seven deadly sins. I think the same is true for comedians. Some of the greatest comedians have manifested several sins. Jack Benny was pride and avarice.

There is a theory, which you can find on the internet, that claims that all the characters on “Gilligan’s Island” were manifestations of the deadly sins. But I believe the producer of the show, Sherwood Schwartz, based each of the characters on a classic comedian. Since classic comics all followed the “manifestation of sin” formula, it was inevitable that all the sins would be represented. (A source close to Sherwood confirms that this is the greater likelihood.)

Gilligan and the Skipper seem to be based on Laurel and Hardy, but they also represent Gluttony and Anger. Thurston Howell was a ringer for Jack Benny, but he also represented Avarice. Ginger Grant did a great Marilyn Monroe, but the sin was Lust.

A comic I worked with once, a guy named Uncle Dirty (real name: Robert Altman), was talking backstage about the nature of laughter. He mentioned that laughter isn’t necessarily a good thing. He believed it was similar to the sound a cat makes when it’s angry, and notes that when a chimpanzee, our closest animal relative, makes a face that we suppose is laughter, it is actually the chimpanzee face of terror.

The legend is, Uncle Dirty killed his career on an episode of the “Mike Douglas Show.” He was sitting on the panel with Billy Graham. He leaned over, grabbed Billy’s lapel, and started stroking it with his thumb, checking out the material. “Dr. Graham,” he asked, “did Jesus buy you that $800 suit?”

Perhaps his own confrontational nature led him to think of the audience as adversarial. Dana Gould, who for six years wrote for “The Simpsons,” used to do stand-up, and is recognized as one of the most brilliant artists ever to hold onto a microphone. He said in an article for Gothamist, “When I was a younger comic, [Kevin Rooney] said something to me that really changed my perspective the instant I heard it. It was, ‘The audience wants to like you, but they want to know that you like them.’ I wish I knew the date he told me, ’cause that changed everything.”

As I’ve matured as a performer, and a businessman, I’ve learned that Dana’s perspective is probably correct. Sure there is a potential for an aggressive comic to make it out there, but he will only be marketable to people who are in on the joke.

I really don’t know where I’m going with all this, other than to give you an idea of what a comic thinks of humor. For some reason, because I tell jokes for a living, it’s expected that I am an expert on what is and isn’t funny. I’m not. If I had any idea of what is funny, I would be a household name by now.

I do know what I find funny. The second hardest task in comedy (and probably the most important) is finding other people who laugh at the same things you do. Lenny Bruce said that he wasn’t looking to be a big star. He knew full well that he would never appeal to everybody. What he was looking for was 100,000 fans that loved him so much they would each give him ten dollars a year. That is what I’ve been trying to do.

Finding libertarians was a really good start. David Friedman notwithstanding, I’ve found that many libertarians really get a kick out of my stuff – perhaps too big a kick. Some

First the antismokers wanted to go into bars where people smoked, so they banned indoor smoking. Everybody had to step outside to smoke. Now that they’re all alone in the bars, the antismokers want to go outside themselves.

of the stuff I was doing in the mid-’90s was so over the top that only libertarians found me funny. It is important to remember, in marketing, that even though you might be a niche product, you still want that niche to be as large as possible.

Louis Lee, the owner of the Acme Comedy Company, is my patron. He gives me at least a couple of weeks a year at his club, and I cherish them. It is an incredible place to work on material, because he has trained his audience to pay attention and appreciate the art. Because of Louis, Minneapolis standup audiences hold respect for comedy; they hold it in the reverence normally accorded to operas and theater productions.He gives me the freedom to explore bits and concepts, and I exploit his good nature. A week at Acme is the best place to try stuff.

Today, Acme is one of the top comedy clubs in the nation, and some of the biggest names in the industry have graced its stage. Robin Williams, Lewis Black, and Frank Caliendo are just a few of the big ones. But in 1991, when Louis bought it, the Acme Comedy Company was closed, because the bottom had fallen out of the industry. Comedy had become oversaturated. There were far more shows than audiences. What was once novel had become routine.

In an effort to remain solvent, a lot of clubs resorted to “paper” to keep the doors open. This is the practice of holding a fake contest and telling somebody he “won” ten free passes to the comedy show. By jacking up the drink prices and making it a two-drink minimum, the clubs were able to recoup the cost.

The “prize” of free passes was sometimes awarded to a business card dropped into a fishbowl. Sometimes it went to whoever picked up the phone when a telemarketer called. Some clubs even resorted to automatic dialing machines, going through the entire phonebook sequentially. The cleverest way of handing out tickets that I remember from those days was on a radio show. We’d promise to give away tickets to the tenth caller and the phones would light up. The OJ would hit the calls one by one and say, “Hi, you’re the tenth caller!’

As you can imagine, tactics like this wouldn’t work forever. Eventually the listeners would say to themselves, hey, how come I’m always the tenth caller? Fishbowl “contests” became so routine that the fishbowls got known as the place where you drop your card to get free tickets. Eventually comedy became devalued, and people no longer appreciated it. The crowd became drunker and rowdier as the clubs catered to the lowest common denominator. With revenue streams being heavily dependent on drink sales, of course the crowds started getting drunker.

There got to be a game of chicken between the club owners. Nobody was making any money, but all the clubs knew that at least one club would survive in each market. So they

Uncle Dirty started stroking Billy’s lapel, checking out the material. “Dr. Graham,” he asked, “did Jesus buy you that $800 suit?

held on to their losing hands way too long, each hoping that the other guys would fold first. In many cases, all of them went bankrupt and were boarded up.

The recession of 1991 caused a cascade of failing clubs. Probably close to 90% of all full-time rooms closed that year. The ones that stayed open became weekend rooms. The face of the industry changed. Fortunately, the style of comedy I was doing by then fit really nicely with college and corporate events, so I was able to shift almost seamlessly between a club act and an after-dinner speaker performance. I still do the clubs as often as I can, because there is an energy in those rooms that’s just hard to match anywhere else. Some might say I have to, because I’m hopelessly addicted.

I’ve been working for Louis Lee almost since day one, and we always hang late after the show. These evenings are always full of scotch and politics, economics and the latest scoop on what’s going on in the comedy industry. Since Louis has the most sought-after venue for comics, he maintains contact with some of the biggest agents and managers, and I’m always fascinated to learn the latest buzz.

Comedy is a huge business today. Stand-up was once relegated to the guys who would go on during a burlesque show in between the girls, while one was picking up her feathers and popped balloons and the next one was getting into a giant champagne glass. From the ’60s through the ’80s, it became a steppingstone to television comedy. But today the art of stand-up is more sophisticated and varied than ever before. Louis suggests that comedy in the 2000s is like music in the ’70s, when rock ‘n’ roll splintered into punk and new wave and hair metal and at least a hundred other varieties. Comedy is doing the same thing today. There are also at least two dozen full-time theater comedians who pull in a quarter million or more a year just headlining 2,000-seat theaters. Whereas in the 1980s comics had to go on situation comedies to make it big, today comics like Ron White are actually too big for television.

Kids who were too young to remember the saturation of the ’80s are discovering comedy for the very first time. Shows like “Last Comic Standing” have revitalized public interest in the art form, and outlets like YouTube, iTunes, and satellite radio are exposing a new generation of people to my addiction.

Saturday morning I sleep in late. The Scotch was flowing the night before, and I probably had one or two too many. I don’t remember much, but I do know the birds were chirping when Louis dropped me off in front of the hotel. I get up and decide to take a walk to clear my head. That’s when it comes to me, a way into the bit that I’ve been trying to square out. Minneapolis is home to the largest Somali immigrant population in America. I think to myself: “Oh that explains it. I thought it was a little early for ‘Dress Like a Pirate Day.'”

It’s hilarious to me, and I can’t wait to try it onstage. I plan to use the bit to start talking about President Obama’s failing to apprehend the pirates, and then segue from Obama jokes into living in a post-racial America, and paying off the debt of slavery. It may work.

And the first show Saturday, it does. It kills, as a matter of fact. It works so well that I’m able to improvise a little and actually script a portion of the bit onstage. It’s magical when this happens. The audience loves me.

Second show, not so much. No sooner have I made the Somali joke than a heckler starts shouting things about turning the trailer over on my white cracker ass, and I bail on the bit long before I even get to talk about slavery reparations. Fortunately Louis isn’t around to witness my failure. Apparently, he is at that age where I’m interesting enough to get him to listen to me past 3 a.m. only once in a while. I hate to leave after a week like this. But there’ve been only a couple of down days, and soon 111 be on the road again, with a new chance to work the bit.

I think that’s called a relapse.