In 1996, President Bill Clinton declared that lithe era of big government is over.” In America’s cities, however, it has only just begun. City officials are making ever more ambitious grabs at power. Their goal is to protect their constituents from themselves. Their means are regulations, bans, and moratoriums on common goods and practices. The results? More Jay Leno jokes about the daily wackiness of American politics – and something more serious, too: economic harm and curtailment of free- dom. When Belmont, CA, recently banned all smoking except inside the doors of owner-occupied houses, it was going a long way toward assuming the power to tell people what they could do about everything.

It remains to be seen how far this will go, but the omens are, well, ominous. Try this one:

In June 2007, the town council of tiny Delcambre, LA, unanimously passed an ordinance banning low-hanging “sagging” pants within city limits. Those found committing the fashion faux pas could face a $500 fine or a sentence of up to six months in jail. In a community devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and still in the process of recovering, it would seem that local leaders would have more pressing priorities. But, despite the avalanche of criticism that Delcambre’s official class received for its abuse of the legislative process, more than a dozen municipalities across the country followed suit, passing or considering similar ordinances.

Lamenting the success and popularity of fast-food restaurants in low-income areas, Los Angeles Councilwoman Jan Perry has asked her colleagues to consider a “health zoning law” that would impose a one- to two-year moratorium on new fast-food establishments in her inner-city district, giving time for government planners to attract restaurants “with broader and more healthful food offerings.”

Perry suggested still more limits, arguing that “fast food is primarily the only[!] option for those who live and work here. It’s become a public health issue that residents be given healthier choices.” In Perry’s view, government action is “primarily the only” solution for her poor, undereducated – but, apparently overfed – constituents.

Of course, many of the businesses that Perry wants to get rid of have spent millions of dollars crafting healthier menu options, as well as providing nutritional information to enable their customers to make more informed decisions. And Perry’s constituents, like all other Americans, vote with their feet. If they don’t feel like a cheeseburger and fries on Friday, they don’t have to order them, or even step into a restaurant that sells them. If they make that choice, the food industry – man- aged to maintain profits – will respond to changing forces or file for bankruptcy. Wonder Bread, a longstanding staple in American pantries, has in recent years closed up shop in Oregon and Washington. In August 2007, its corporate parent announced that it would stop baking and selling its famous white loaves in Southern California. Industry experts agreed that Wonder Bread had failed to respond to shifting West Coast trends toward more healthful diets.

While news like this might mean something to sensible people, it makes no impression on the advocates of the nanny state. And it isn’t just “health” that’s at stake for them. It’s morality, or what they define as “social policy.” They need laws to make people good.

In addition to policing consumer health, a key goal of nanny-state intervention is the raising of “sin taxes” on goods and services that don’t comply with social policy goals. This tactic has been employed in many municipalities – most notoriously, perhaps, in New York City.

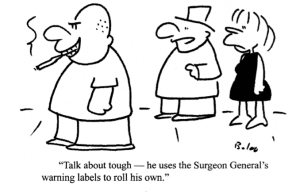

In both 2006 and 2007, Mayor Michael Bloomberg pleaded with New York lawmakers to raise the city’s cigarette tax – already the highest in the nation – by 50 cents a pack. He declared the higher tax “would save the lives of thousands,” especially children. Quoting the mayor’s February 2007 remarks: “experience demonstrates that raising the price of smoking is the surest means of discouraging teenagers from becoming addicted to tobacco.” Fifty cents may not seem like much money – and one doubts that it will mean much to teenagers carrying both a pack of cigs and a thousand dollars worth of electronic equipment – yet it would provide about $20 million dollars for local pork-barrel projects.

But I digress. Bloomberg’s proposal was merely the latest assault on New York City smokers. Launching a number of new antismoker initiatives in 2002, Bloomberg convinced lawmakers to raise the city’s cigarette tax from eight cents to $1.50, a 1,775% tax increase, which he claimed wasn’t nearly high enough. As he said at the time: “if it were totally up to me, I would raise the cigarette tax so high the revenues from it would go to zero.” Did I hear “prohibition”?

Despite Bloomberg’s pieties, it’s clear that, with city and state tobacco taxes raising the price of a pack of cigarettes to more than $7, smokers have become the love-hate interest of politicians who are unable to balance their budgets.

After the 2002 tax hike, NYC cigarette tax revenue soared from less than $30 million to nearly $160 million a year. Yet the nanny retains her piety. Bloomberg is trying to take his cigarette tax global, with the help of the United Nations. The UN’s World Health Organization announced in 2006 that Bloomberg had pledged $125 million of his own money for a Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI) designed to end “the global tobacco epidemic.” The special target is 15 nations (including Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India), upon which an international cadre of nanny- state activists, funded by Bloomberg, is preparing to descend. Their lofty social-policy purpose is to levy high cigarette taxes, to restrict tobacco advertising, to ban smoking in pub- lic places, and otherwise, by nagging and restricting, to “help make the world tobacco-free.”

Bloomberg discussed his passion for the cause in an op-ed published by the British medical journal Lancet (May 19, 2007). He touted the accomplishments of his antismoker campaign in New York City and noted with pride that “tax increases raised the legal retail price of cigarettes by 32%… virtually all indoor workplaces, including bars and restaurants, were made smoke-free, despite vocal opposition. Hard-hitting print and broadcast antitobacco advertising campaigns were initiated … smokers were provided with free courses of nicotine-replacement treatment to help them quit; nearly 20% of smokers were reached over 3 years. Rigorous surveillance was established.”

Few government officials in the Western Hemisphere have tried to institute the sudden and radical nanny-statism of Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez, who in the fall of 2007 announced new and higher taxes on tobacco products, alcohol, luxury cars, and even artwork. It was a puritanical attempt to mold Venezuelans into his conception of the socialist “New Man.” Said Chavez: “There are people who spend what is necessary, but then there are some who spend and spend. I am looking to put a tax on this.” Whether we are supposed to understand that the New Man is modeled on Chavez’s own personal choices is unclear, although news agencies quoted the leftist leader as confessing to have enjoyed a drag and a sip from time to time. His aim, however, is to make such activities unaffordable by others.

It’s worth noting that the recent wave of sin taxes followed an earlier Chavez decree to ban alcohol sales nationwide during Holy Week – a move that observers suspected had less to do with appealing to Christians at home than with appeasing the leaders of the Islamic RepUblic of Iran, which prohibits the sale and consumption of alcohol carte blanche. Chavez has sought stronger diplomatic ties with them.

Whatever their specific motivation, these nanny-state policies are easy to ridicule for their elitist “humanitarianism” and boutique authoritarianism. But their effects are more pernicious than denying Marlboros or Big Macs to hoi polloi. There’s a damaging economic effect as well.

Peripheral government regulations introduce inefficiencies that cause suboptimal asset allocation by businesses and consumers, impairing their ability to respond to market forces efficiently. Optimally, a firm would seek to maximize profits by setting its marginal revenue equal to its marginal costs. However, when an economic disincentive is imposed, a “wedge” is driven between the price paid by the consumer and the price charged by the producer.

The costs to society that are created by artificial market- place inefficiencies are known as “deadweight losses,” as they are foregone economic outputs that could have yielded greater productivity, greater revenue for businesses, and lower prices for consumers. Such disincentives arise from the imposition of taxes or government mandates that yield fewer incentives for markets to produce greater outputs and control higher costs.

Despite the popular perception that new nanny-state taxes and red tape will be somehow absorbed by commerce, their costs get passed onto the consumer, who in turn pays them through higher prices and limited choice. To suggest that

Despite the popular perception that nanny- state taxes and red tape will be absorbed by commerce, their costs get passed to the consumers.

business taxes are simply absorbed by private industry is cynically misleading. A June 2005 study of San Francisco’s myriad local business fees and taxes found that excessive municipal government surcharges inevitably seep into the costs of consumer goods and services; it was estimated that a $2 cup of coffee from an outdoor cafe in San Francisco includes 64 cents, or 32%, in fees and taxes (and that figure excludes state and federal income and payroll taxes).

Anyone who knows that he has to work through a maze of local, state, and federal regulations and tax codes before launching a new business may well just give up, especially if the business plan lies on the uncertain edge of innovation. It’s impossible to measure all the costs of niggling, nanny- state regulations. But some of the compliance costs of new and higher taxes (record keeping, education, shipping, form preparation, etc.) are measurable, and they have been proven to reduce economic output significantly. In 2001, the Tax Foundation estimated that for the hours that businesses and individual taxpayers take each year simply to comply with the federal tax code, the overall compliance cost was almost 12 cents for every dollar collected in federal taxes – a gargantuan amount.

Nanny-state laws don’t just take money from the taxpayers and consumers; they also increase the size of government by raising higher collection costs for new taxes and fees, as they require additional municipal manpower and resources for implementation and operations. Treasury or tax collector staff may need to be augmented, or existing staff may be assigned these new responsibilities, requiring costly overtime hours. Physical costs – such as postage and mailing, purchasing industry computer software and hardware and other implements – add to the overhead. None of this, mind you, has anything to do with the real functions of government – preventing force and fraud.

Strangely – and, from the standpoint of the municipal nannies, quite unexpectedly – people react to this interference.

Faced with rising red tape and government fees, businesses pick up and move to less-regulated jurisdictions.

Consumers who are able to live or shop in other jurisdictions do so. Among those who stay, some will seek out a black market to purchase cheaper stolen or smuggled goods. Since Sept. 11, 2001, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives has noted a spike in illicit cigarette trafficking, as people reap profits from buying mass quantities of cigarettes in low-tax states and selling them on the black market in high- tax states. The profit in these activities can be rich. And deadly. As the Washington Post reported in 2004, federal authorities have uncovered numerous schemes to exploit nanny-state policies for the benefit of al Qaeda, Hamas, and Hezbollah.

Using the state to enforce the social standards and moral agenda of a few results in a loss of personal freedom for all. The rapid rise of the nanny state in America’s cities speaks to the pervasive political incentive to overreact and overregulate in the face of crises and calamities that are sensationalized – or created – by the 24-hour news media cycle. It also speaks to the breakdown of true community. Neighborly relation- ships foster communication, cooperation, and friendship – a factor that is vital in such cities as Los Angeles, where the assimilation of newcomers is particularly important. In a real community, most differences can be resolved privately. In the nanny state, by contrast, people are encouraged to depend on the state when there is any dispute about noise or land use, or even plants or toys in people’s front yards. Few circumstances could be worse for the sense of individual responsibility and thoughtful consideration of other people on which community depends.

The nanny state also harms the core social unit, the family. Not allowing parents to educate their children on the importance of personal responsibility and the consequences of their actions inhibits the growth of self-reliant adults. Of course, statists want citizens to be immature and malleable. As economics professor Glen Whitman suggests, “when individuals

As Michael Bloomberg said at the time: “if it were totally up to me, I would raise the cigarette tax so high the revenues from it would go to zero.” Did I hear “prohibition “?

bear the full costs and receive the full benefits of their own actions, the justification for government involvement is much weaker.” There’s no place for a nanny once the children have grown up.

Many nanny-state laws attempt to wrestle individuals away from their desire for modern material goods – video games, automobiles, the internet, fast food, cigarettes – that the nannies don’t like. But the freedom to choose how one spends his income, time, and other resources is meaningless if it is limited to a handful of options approved by the city council.

Ceding even piecemeal losses of personal freedom can have adire effect down the road. UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh made a study of how the “slippery slope” phenomenon relates to government regulations (“Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope,” Harvard Law Review 116 [Feb. 2003]). Volokh concluded that taking small steps to control the use of some- thing can facilitate later steps to ban it completely; for instance, mandatory gun registration makes firearm confiscation more feasible. Using the example of local legislation in New Jersey to outlaw cigarette machines in 1993, Volokh noted the progression from regulation to prohibition. According to a 1993 New York Times article:

Sandra Starr, vice chairwoman of the Princeton Regional

Health Commission … said there is no “slippery slope” toward a total ban on smoking in public places. “The commission’s overriding concern,” she said, “is access to the machines by minors.”

In June 2000, the Record (the major newspaper in Bergen County, N.J.) noted that

“the Princeton Regional Health Commission took a bold step to protect its citizens by enacting a ban on smoking in all public places of accommodation, including restaurants and taverns. . . . In doing so, Princeton has paved the way for other municipalities to institute similar bans.”

So, when it comes to cigarettes in New Jersey, the slippery slope of the nanny state is approximately seven years long.

With all the threats nanny-state laws pose to economic and other personal freedoms, it’s clear that champions of liberty must move beyond merely mocking the nannies. Ground zero in the fight against oppressive government will be America’s cities. As David Harsanyi, author of the book “Nanny State,” remarked in a 2007 interview, “most nanny state initiatives begin on a local level.” As the success of nanny-state ordinances continues, free-market forces should consider a collaborative effort to end the erosion of individual liberties. It’s already begun, in fact. Some free-market advocates have published quantifiable comparative analyses or “indexes” to raise awareness of encroaching laws. The Cato Institute, along with more than 70 thinktanks across the globe, publishes the “Economic Freedom of the World,” an annual index that assesses the state of sovereign laws affecting businesses, consumers, and entrepreneurship. The Heritage Foundation releases an annual Index of Economic Freedom,

The rise of the nanny state in America’s cities speaks to the incentive to overreact and over- regulate in the face of crises and calamities.

which examines the regulatory treatment of ten specific freedoms in 161 countries. Other thinktanks effectively examine narrower regulatory issues. The San Francisco-based Pacific Research Institute publishes an impressive array of indexes of regulatory environments across the 50 states, including an “Economic Freedom Index,” “Tort Liability Index,” and “Health Ownership Index.”

This should go farther. Advocates and researchers should weigh the merits of an urban “citizen’s freedom index” that measures the strength of nanny-state regulations in at least the 20 largest U.S. cities. This index would examine the comparative strength and activity of nanny-state ordinances in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Phoenix, Philadelphia, San Antonio, San Diego, Dallas, San Jose, Detroit, Jacksonville, Indianapolis, San Francisco, Columbus, Austin, Memphis,

When it comes to cigarettes in New Jersey, the slippery slope of the nanny state is approximately seven years long.

Fort Worth, Baltimore, and Charlotte. These metropolises are ideal for greater regulatory scrutiny, since they all have pertinent data readily available to the public and mass media out- lets that local elected officials respect.

What would such a study measure? Nanny-state laws seem to come in four areas:

1. The use and availability of federally-controlled goods, such as alcohol, tobacco, and firearms;

2. The use and availability of property, such as houses, food, and clothing;

3. The levy of new and higher excise taxes, fees, and surcharges on consumer goods and services;

4. The imposition of restrictions on advertising and other mass communication.

Results could be published in an easy-to-read format and publicized through localized press releases that would bring greater public awareness to the losses and gains of freedom in each city. Lawmakers in notoriously pro-nanny cities could be identified, and lawmakers who seek to expand freedom could receive an annual award of esteem. Such an index would thus be useful in increasing public accountability of lawmakers, while it gave incentives to local officials of all political stripes to expand consumer choice, encourage personal responsibility, and protect individual liberty.

Did I say “personal responsibility,” yet again? I did. Some of the nanny state’s pet causes – consumer safety, smoking, obesity, substance abuse, over-indebtedness – are serious problems; but they are problems that should be met by individuals. The internet can help; so can watchdog organizations such as the Consumers Union; so can private organizations devoted to education and encouragement of helpfUl action. But if you want to see the results of government social engineering, I would advise you to look at the wreckage of the Great Society programs of the 1960s and 1970s. The fact that they are now being replaced by an infinity of Little Society nanny programs does not mean that government interference is any likelier to achieve the results intended.

Ronald Reagan said, “Government exists to protect us from each other. Where government has gone beyond its limits is in deciding to protect us from ourselves.” Pressuring individuals through law to make “better” decisions in their lives is contrary to the spirit of our Founding Fathers – and has no place in the town halls and city councils of America.