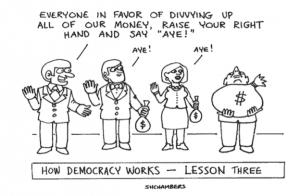

Each election cycle, Libertarian Party candidates are forced to contend with a lack of visibility, voter apathy, inability to compete in fundraising, and ballot access restrictions by the major parties. According to a new book, the party must also contend with another challenge: election and reelection to major public office depends not upon appealing to majority opinion, but rather upon putting together and maintaining coalitions of passionate minorities.

In “Tyranny of the Minority: The Subconstituency Politics Theory of Representation” (Temple University Press, 2009), Benjamin Bishin, a professor of political science at UC Riverside, lays out a theory “in which groups of intense and active citizens, rather than the citizenry as a whole, constrain legislator behavior.” This theory, which the author labels “the subconstituency politics theory of representation,” states that high-level officeholders win election and reelection by first building and then maintaining coalitions of politically active groups focused primarily on single issues. Once in office, successful politicians promote the agendas of their activist supporters even when such agendas are opposed by a majority of their constituents:

“Subconstituency politics holds that, owing to the fact that different voters care about different issues with differing

levels of intensity, the will of minorities is often represented at the majority’s expense. Politicians appeal to the preferences of passionate subconstituencies to build coalitions of intense supporters who are more likely to participate. . . . [They] appeal to minority preferences over those of the majority when the benefit of advocating the minority’s position outweighs the cost of alienating the less interested majority.

Bishin’s arguments are credible. He uses real-world examples to test his theory of political representation against the explanations of more mainstream theories. He cites numerous references to bolster his arguments and provide resources for those who wish to explore both sides of the issue further. And, although the Libertarian Party receives no mention in the book, there are clearly major implications for party strategy if Bishin’s theory is correct. After all, one of the party’s major stated goals is the election of libertarians to public office.

Over the course of nearly four decades, several hundred Libertarian Party members have won local office, along with a sprinkling of state legislative seats. So far, however, the party has not been able to claim any U.S. Senate or congressional seats, or any major offices at the state level. If subconstituency theory is correct, does it help explain the limited success of current Libertarian Party strategy?

At first glance, the LP would appear to be a haven for passionate minorities focused on single issues. In theory, this should boost the prospects of its candidates at election time; yet in reality, such candidates are forced to contend with a major complicating factor: the existence of opposing single-issue groups with superior firepower.

At the congressional level and above, Libertarian candidates generally promote the party platform on a wide range of issues: civil liberties, tax policy, education, drug decriminalization, healthcare, and national defense, to name just a few. But although Libertarian candidates appeal to those who are passionately active on a wide range of issues, they encounter heavy opposition from well-entrenched and well- funded activists on the opposite side. To take just one obvious example, a huge majority of the public opposes the libertarian position of removing government entirely from the field of education. Augmenting this public hostility are many government education advocacy groups, especially teachers’ unions, that are extremely active politically. This is a formidable disadvantage, one that is impossible for Libertarian candidates to overcome, even if they are able to compete on an otherwise level playing field. Subconstituency theory suggests that the opposition of powerful activist groups, by itself, dooms any chance of a Libertarian victory in a contested election for higher public office.

Assuming this is true, what can libertarians do? Is it possible to do anything at all? And should their efforts be focused on the Libertarian Party?

To answer these questions, we must take a fresh look at the electoral landscape. As we do so, we will discover that subconstituency theory offers alternative means for libertarians to boost their effectiveness in the political arena.

To begin with, it is important to recognize that electoral strategy is dictated by each candidate’s perception of how the political process works. Libertarians for the most part base their strategies on the traditional theory of representation. Bishin refers to this as “the demand model, which is characterized by politicians who consider the views of their entire district when making decisions, and to try to do what constituents either want or are likely to want.” Bishin argues that this model is flawed; subconstituency theory better explains politicians’ behavior both on the campaign trail and in office.

According to Bishin, candidates frame their policy and non-policy (symbolic) positions to attract supporters with similar views. Supporters thus attracted take on a “group identity” with a shared outlook on issues and a shared intensity. Successful candidates attract or create multiple groups of passionate supporters by staking out positions on a variety of hot-button issues. These groups are highly motivated to provide votes, money, volunteer time, and other important resources to achieve the election of their candidates. Successful candidates return the favor by promoting legislation that reflects the views of their activist coalitions, ensuring their continuing support in subsequent campaigns.

What if the agenda of an incumbent’s activist coalition collides with the wishes of a majority of voters in his or her district? Usually the activist coalition will have its way: “Precisely because the average citizen does not feel intensely about [an] issue, a candidate’s advocacy of the minority position seldom prevents her from obtaining the support of the voter who is opposed to the position but does not feel strongly about the issue.” This is a plausible explanation of why both liberals and conservatives are able to win reelection in districts where the majority of voters hold views contrary to their own on many issues.

In Bishin’s model, party affiliation is a less important influence on policy than coalitions of issue-oriented activist groups. Elected representatives frequently cast roll call votes contrary to their party’s stated position, in order to cater to the coalitions that support them. Party leaders generally tolerate such behavior because they see it as necessary to ensure their members’ reelection, though at some cost to the party’s own program.

According to subconstituency theory, issue visibility also takes a back seat to organized activism in influencing a legislator’s vote. If the public at large does not hold strong opinions on an issue, increasing its visibility will not create sufficient pressure on an officeholder to abandon his commitments to his carefully constructed coalition of activist supporters. “The influences on legislators’ behavior change with issue visibility only to the extent that visibility serves to activate new group identities with which legislators are forced to reckon.”

As an example of this process, Bishin cites the fate of a 2007 resolution in the House of Representatives that made reference to events that occurred nearly a century ago. The resolution, which declared the killings of Armenians in Turkey during World War I to be “genocide,” attracted 229 cosponsors, a number more than sufficient for passage. Initially this resolution lacked visibility and interest among the general public. It did, however, evoke intense feelings within the Armenian and Turkish communities. The government of Turkey reacted by withdrawing its ambassador and threatening to close its airports to U.S. flights carrying supplies to soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. In response, many House members withdrew their support for the resolution. To date, the measure has not been brought up for a full House vote. Proponents are concerned that they may not have sufficient votes to pass the resolution.

Bishin attributes this turnaround to the influence of a powerful subconstituency group, military veterans. Once the issue became highly visible, veterans’ groups grew concerned that passage of the resolution would damage the war effort and increase the risk to troops fighting in the field. They used their leverage as a powerful subconstituency to beat back the resolution, even though overall public opinion regarding the issue was largely unchanged. Bishin observes that the districts of House members who withdrew their support contained a significantly higher number of veterans than districts of members who continued to back the resolution.

This outcome illustrates the impressive influence that sub- constituency groups can achieve within the political process. Unfortunately, it is difficult to identify a subconstituency group that could turn things around for the Libertarian Party. Not only are powerful subconstituency groups — greens, unions, public employees, professional cartels, and social conservatives, to name a few — adamantly opposed to lib- ertarianism, but there is little prospect of activating a new subconstituency to support any issue that the LP somehow manages to raise to visibility. Issues that currently engage the voting public are already being promoted by activist groups, many of which have strong ties to one or both major parties. Even groups that agree with libertarians on specific issues are not likely to affiliate publicly with the Libertarian Party, since they perceive — correctly — that the party lacks the political resources needed to advance their agendas.

The Libertarian Party is composed of committed and hard-working political activists who feel strongly about issues relating to individual liberty. But the party itself is not structured in a way that permits it to gain traction as a subconstituency group able to influence legislators. The party takes positions on a wide range of issues, making it difficult to gain support from mainstream politicians who are not in agreement with all of its views. In addition, virtually all holders of higher office are members of a major party, so they will discount any Libertarian Party proposals as coming from a competitor rather than a supporter. The only meaningful leverage the Libertarian Party can exert on major party candidates is the threat to draw votes away from one candidate in favor of the other, and the major party margin of victory is usually larger than the number of votes cast for the LP.

As individuals, libertarians are free to join or form single-issue subconstituency groups and work within them to advance the issues they most care about. Many have already done so. The effectiveness of libertarians working within such groups depends on a number of factors. If the group is very large and well organized (as is the National Rifle Association, for example) the presence or absence of a few libertarians is not likely to make a significant difference to any political outcome. If the group is opposed by a better funded, better connected band of activists, such as the entitlements lobby that vigorously opposes Social Security privatization, libertarians will likewise have little political impact.

But assuming that the subconstituency model is correct, the best opportunity for libertarians to make a difference is to work within single-issue groups that already enjoy a relatively small but significant amount of public and legislator support. These include groups that favor homeschooling and individual privacy, and groups that oppose specific taxes. The impact of libertarians can be greatly enhanced if they are able to gain leadership positions within such groups, since this will permit them to interact with legislators and other influential political players at the policy level — thus becoming, themselves, an effective subconstituency group.

One example of a subconstituency group with significant libertarian influence is the Campaign for Liberty, a nationwide organization formed in June 2008 by Ron Paul and many of his supporters following his bid for the Republican presidential nomination. The group’s principal mission, as stated on its website, is “to promote and defend the great American principles of individual liberty, constitutional government, sound money, free markets, and a noninterventionist foreign policy, by means of educational and political activity.” In launching the group, Ron Paul emphasized its focus as a vehicle for political reform: “We will make our presence felt at every level of government. We will keep an eye on Congress, and lobby against legislation that threatens us. And we will identify and support candidates who champion our great ideas.” Clearly the Campaign for Liberty meets Bishin’s criteria for an activist subconstituency group.

The political influence of the Campaign for Liberty has become significant in a remarkably short period of time. Although Ron Paul is a Republican, and the Campaign for Liberty is composed primarily of conservatives and libertarians, it is receiving a surprising amount of bipartisan support for one of its key legislative proposals: an audit of the Federal Reserve System by the Government Accountability Office. As of this writing, the proposed legislation has been cosponsored by a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives, including

Subconstituency theory suggests that the opposition of powerful activist groups, by itself, dooms any chance of a libertarian victory in a contested election for higher public office.

178 Republicans and 112 Democrats. The U.S. Senate version has 25 cosponsors, six of them Democrats. This impressive level of legislative support has been made possible by a nationwide, coordinated grassroots petitioning and lobbying effort by the Campaign for Liberty. It demonstrates the influence that pro-freedom activists can achieve by applying the strategies and tactics of subconstituency politics.

This does not mean that purely libertarian political activism should be abandoned or sidelined. The Libertarian Party has a vital role to play as a recruiting and training organization for pro-freedom political activists, as a “home base” for those seeking political asylum from the two major parties, and as a springboard for electing libertarians to local offices. These are all important reasons to make sure the Libertarian Party continues to exist. But to have a meaningful voice in public policy decisions, libertarian activists must be willing to work with compatible subconstituency groups that can command the continuing attention of legislators and other policymakers.