The federal budget, released Feb. 4, was refreshing. Rather than just the usual puff rhetoric used to justify increased spending, the new Bush budget includes tough talk about federal programs that don’t work. Consider the budget discussion on education: “Since 1997, appropriations for Department of Education programs have increased an average of 13% per year, despite an almost total absence of evidence that the programs were effective.” Right on! Let’s cut that bloated education budget!

But then you look at the actual budget numbers, and you find a total disconnect between rhetoric and reality. Proposed Department of Education outlays next year are $53.8 billion, up from $47.6 billion this year – an increase of 13%, virtually the same increase that was disparaged in the text. The disconnect between the language and the actual proposals is evident on the tax side of the budget as well. Tax simplification is discussed, and tax reform policy studies are promised, but a slew of complex targeted tax credits are actually delivered.

All in all, the Bush budget contains a striking lack of boldness with regard to constraining government, especially for a Republican president with sky-high popularity and two and a half years to go before re-election.

The Rhetoric

A major theme of the Bush budget is reforming government to make it more efficient. Yes, we’ve heard that before. Bill Clinton’s last budget declared that he and Al Gore were successful in “improving performance through better management” with Gore’s” reinventing government” campaign.

This year’s budget introduces an Executive Branch Management Scorecard, which gives each federal agency a green, yellow, or red grade for their performance in various categories. Of 130 grades given, 110 were red for” unsatisfactory” this year. I guess Gore’s eight years of reinvention didn’t work after all. The budget also graded a sampling of programs in each department as “effective,” “ineffective,” or “unknown.” Many were scored ineffective.

I don’t know whether Bush and his budget chief, Mitch Daniels, will be successful in improving government management, but the budget doesn’t reveal that they have any interest in improving management or shrinking the federal government. The budget seeks an “efficient delivery of farm aid,” but proposes boosting the farm aid price tag by $74 billion over ten years. Ronald Reagan, and the Republicans who took control of Congress in 1994, sought at least some major program terminations. The Republican Party of 2002 has become more like Tony Blair’s government, as described by Stephen Berry in Liberty (March, 2002), which aims to bring more market-oriented management to government administration.

Take Amtrak. The Bush budget heaps scorn on it, saying it has “utterly failed” to wean itself off subsidies, that its recent mortgaging of Penn Station in New York is a “financial absurdity,” and that, overall, it is a “futile system.” The budget’s solution is that “passenger train service should be founded on a partnership between the federal government, the states, and the private sector.” A partnership? Why not outright privatization? As Berry notes in his piece on Britain, “I worry that, as with the railways, a partial, half-hearted, and bungled privatization will bring a host of problems in its wake and tend to discredit the market.”

Or take the colossus called the Department of Health and Human Services, which will shell out $459 billion this year for Medicare, Medicaid, and a huge array of other programs. The budget notes that”in few federal agencies is the need for organizational reform more acute than at HHS … a complex web of ever-proliferating offices has distanced HHS from the citizens it serves, and has produced a patchwork of uncoordinated and duplicative management practices.” HHS has 40 human resources offices and 70 public and legislative affairs offices. The solution? A nine percent increase in its discretionary budget.

I give kudos to Mitch Daniels for trying to separate out the most bungling and wasteful federal programs from the

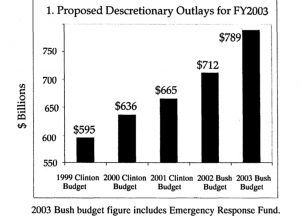

Bush’s budget for 2003 is $124 billion greater than what President Clinton proposed for 2003 in his final budget.

rest with his new rating system. At least this will give smaller-government advocates more ammunition. Perhaps after a few more years of failing grades, the administration might consider ending a program or two. Of course, by then it will be time for the next election and nobody will be interested in cutting anything.

The Numbers

As most policy wonks know, the federal government divides $2.1 trillion in annual outlays between mandatory spending, discretionary spending, and interest. Mandatory spending includes programs, such as Social Security, that are on an autopilot growth path. Discretionary spending includes defense and non-defense spending that needs to be appropriated annually.

In recent years, mandatory spending has been growing at about the same rate as overall economic growth. But this is the calm before the storm that will begin when baby boomers start retiring in 2008. At that time, Social Security and Medicare costs will begin to explode, unless we reform or privatize them before that time.

The real action lately has been on the discretionary side of the budget. Discretionary outlays will rise at an annual average rate of 7.4% between fiscal 1998 and 2003. This spending burst comes after a temporary lull in the mid-1990s caused by falling defense spending, congressional spending caps, concern over high deficits, and the efforts of the new Republican majority in Congress. Whatever discipline there was evaporated after Congress passed the first balanced budget in 29 years in fiscal 1998.

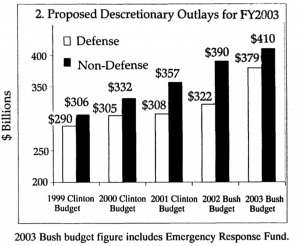

One way to see how discretionary spending has ballooned is to compare what had been proposed for fiscal 2003 in prior budgets, compared to the $789 billion Bush is now proposing. Bush’s number for 2003 is $124 billion greater than the $665 billion that President Clinton proposed for 2003 in his final budget two years ago (see Chart 1). And it is a stunning $194 billion, or 33%, greater than Clinton proposed for 2003 in his fiscal 1999 budget. This pattern of constant upward revisions is true for both defense and non- defense spending (see Chart 2).

Each year, Congress and the executive branch up the ante on each other’s spending plans. The executive branch often tries to get as much spending as it can for the next budget year, but then lowballs more distant years to make the long- term budget numbers seem “fiscally responsible.” For example, the Bush budget proposes that annual growth in non- defense discretionary outlays decline roughly one percent in 2005 and 2006. Clearly that’s wishful thinking, especially since Bush is not preparing to make that happen by terminating programs. So the only fair measure of spending restraint is how much money the administration is demanding right now. Bush’s budget has non-defense outlays rising 9.7% in fiscal 2002 and six percent in 2003 (excluding the Emergency Response Fund).

When the current discretionary spending spree will slow down is not clear. Bush was successful in his strategy of getting as much of the surplus off the table as he could with his tax cut last year. But now he is asking for fiscal discipline from Congress while larding up his favorite programs. The only major departments that even get a light trim are Justice, Labor, the EPA, and the Corps of Engineers. This is more than matched by big increases at Veterans Affairs, Transportation, Health and Human Services, and others. Bush is, of course, also proposing huge spending increases for defense and other security-related agencies such as FEMA.

When you look at the details to see what is proposed for programs traditionally on the conservative-libertarian hit

Bush is asking for fiscal discipline from Congress while larding up his favorite programs.

list, you don’t see many cuts either. Foreign aid and the Peace Corps have big increases. Spending for both the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Endowment the Arts is increased. Some corporate welfare programs, such as the Advanced Technology Program are trimmed, but few are zeroed out. Clinton’s Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles is terminated, but Bush will continue shoveling taxpayer cash to the auto industry with a new Cooperation Automotive Research program.

Farm Subsidies

Farm subsidies deserve special note as the most appalling spending cave-in by the Bush administration so far. The reform-oriented 1996 farm law expires this year, and Congress is using reauthorization as a chance to increase subsidies substantially. In 1996, the main farm price support program was replaced with payments that were to decline over time. But Congress proceeded to repudiate its own handiwork and soaked taxpayers with four large farm supplemental bills in a row starting in 1998. Subsidies have soared from an average $9 billion per year in the early 1990s to over $20 billion per year today.

Congress could now simply reauthorize current law, which would cost taxpayers roughly $100 billion over the next decade. But Congress and the president have agreed to spend $74 billion above that amount by adding a new price support program and other goodies. The ultimate taxpayer cost could well be much higher. Back in 1996, the cost of the seven-year farm bill was scored at $47 billion, but the actual total subsidy cost will end up being $123 billion. Initially, the Bush administration showed some resistance to farm subsidy increases when Congress began talking about it last year. But in the end, the administration utterly capitulated, and Bush is now giving speeches lauding the new subsidy bill.

In With Tax “Incentives,” Out With Tax Cuts

The tax side of the budget is as much of a disappointment as the spending side. Bush’s tax cut from last year got it mainly right with its focus on marginal rate cuts. This year, Bush calls for the rate cuts to be made permanent, but proposes no new supply-side tax cuts.

It should be noted that even with last year’s tax cut fully phased-in, taxes as a percentage of gross domestic product (CDP) will still be more than 19% and near historic highs.

The Bush tax cut was quite small, amounting to about one percentage point of CDP. Last year’s cut was perhaps all Bush could have pushed through, but he should be pushing for substantial tax cuts every year. After all, the top personal rate will only drop to 35% when fully phased-in, and thus only partly reverses his father’s and Clinton’s tax rate increases.

The disconnect between the rhetoric and the actual proposals appears on the tax side as well. The budget includes a nice section on tax simplification, and the administration plans to come out with a series of policy papers on simplification. But Bush’s tax proposals this year are probably as bad as Clinton’s annual proposals for complicating the tax code with targeted tax incentives. The budget has nonsense tax credits for solar power, wind power, fuel-cell cars, and a special schoolteacher deduction. Aside from expiring provisions, there are 30 proposed tax changes: 20 of them would add complexity. Such targeted tax incentives are doubly bad because they create political constituencies against fundamental tax reform. Environmentalists will have no interest in a flat tax if it takes away their tax break for rooftop solar panels.

The Coming Taxpayer Crunch

The budget includes long-term forecasts for federal spending. These are really scary. They show that with no reform, just three programs, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid will increase in cost by more than five percentage points of CDP between now and 2030. New Congressional Budget Office projections say the increase will be seven percentage points. That may be optimistic if the programs are expanded with add-ons, such as prescription drugs. If these 2030 costs were thrust on us today, it would mean a $700 billion dollar annual tax increase. By comparison, Bush’s tax rebate checks last year saved taxpayers just $40 billion.

So even assuming that the rest of government grows no faster than the overall economy during the next few decades, these programs alone will push federal spending to about 27% of GDP by 2030, up from about 19% today. State and local governments currently add about ten percentage points to the spending total, so assuming these governments don’t grow any bigger, we are looking at a total government cost

of at least 37% of GDP by 2030. That’s over 42% of net national product, the broadest measure of Americans’ income.

If Americans want to limit the federal government to, say, 20% of CDP, then the government has to start shedding all non-core programs and functions. Social Security is obviously a high-priority item to privatize, and the budget does reiterate Bush’s commitment to private Social Security accounts. But in addition to Amtrak, the budget chickens out from proposing privatization for other obvious candidates, such as the Power Marketing Administrations, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the air traffic control system, which the budget deems “ineffective.” Privatization has swept the world, but American policymakers still seem to think it is too radical.

Unfortunately, Bush missed a big opportunity in this budget to begin real reform of government by shrinking it. As a result, he is in danger of being remembered as a big-spending president rather than a tax-cutting president.