Depending on what you’ll accept as a “country,” there are something like 225 of them in the world. I’ve visited about 175 – some many times – and have lived in ten. The problem is that now, even if I revisit a dozen a year, it’s going to take 15 years to get back to all of them. And some are going to turn into more than one country as time goes on – a subject for discussion in the future.

My first visit to Russia was in 1977. The next time was in 1996, and the country had changed radically. In 1977, the only places open to foreigners were Moscow and Leningrad, which were, I assure you, as grim as anything Orwell ever imagined. By 1996 – just five years after the collapse of the USSR – those cities had been transformed. They were almost indistinguishable from any Western European metropolis. And today even the old factories along the river have been converted into fashionable lofts.

But outside of Moscow and St. Petersburg, which attracted all the money and talent, Russia in 1996 was still a depressing Third World country. On my recent trip, however, I visited the provincial capital of Astrakhan and found a feeling of relaxed elegance reminiscent of Savannah or Charleston. I’m increasingly convinced that development in Russia is more than just a Potemkin village in Moscow.

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin, who supposedly set up a string of phony, storefront villages to impress Empress Catherine on her tour of the Ukraine and Crimea in the late 18th century, seemed to set the example for the Soviets. Anybody, including myself, who visited the country in the old days could tell it was backward, with nothing going for it but a bloated military. Everybody, that is, except the CIA, whose estimates of the Soviet economy were based on fictional and nonsensical statistics published by the

Soviets themselves and were detached from even the most rudimentary common sense.

My latest trip proved things have changed again. Moscow, when I was there in September, was fully up to European standards. I spent several days wandering around with myoid friend Mark Gould, who’s lived there for most of the last 15 years.

It’s helpful to have a local show you around anywhere, of course. And whenever I don’t have a good local contact, it never takes me longer than 24 hours to groove into a city. I simply set up appointments with lawyers, real estate agents, and art galleries. All of them are happy to make time for a well-heeled foreigner. And after a day of appointments, it never fails that I’ve found someone in each profession that I’ll be socializing with. Within 48 hours, I typically know more people than I have time to call. Going to a place ·and doing the typical tourist thing is the height of travel idiocy. But since boobus americanus doesn’t even travel abroad to start with, perhaps that makes him less than an idiot. No wonder b. americanus thought sending the military to Iraq was a good idea, even though he couldn’t find the country on a map.

A friend of mine has always said he wouldn’t put a nickel into Russia, based on his feeling that the place is simply too corrupt and is overrun by mafia gangs. I once concurred with that opinion, but increasingly I believe that – partly because of better communications and transportation, partly an obviously increasing standard of living, and partly the Putin regime, Russia is becoming a normal country. It’s past the stage where the main imports are stolen cars and the main exports are prostitutes.

I have mixed feelings about Putin, the ex-KGB spy. On the one hand, he’s cut the income tax to a flat 13%, supports the Russian Central Bank at least doubling its gold reserves, and suppressed the mafia and kleptocratic oligarchs. On the other hand, he’s strengthened the Russian state itself which, in the long run, is the biggest danger to everyone concerned. So far, however, I’m forced to say he’s been a net positive.

Anyway, while a lot has changed in Moscow, the city still retains elements of Wild East charm, as when our taxi went a quarter mile past our freeway exit and then back up against traffic to try again. But, then, Russian cabbies in New York have done worse.

Kalmykia

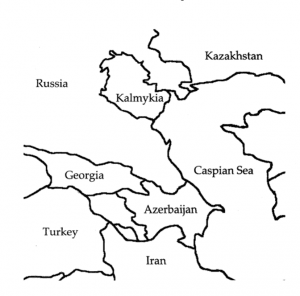

Kalmykia is one of those places that could be, and I’d say should be, and perhaps one day will be, an independent country. What purpose is served by sending revenues upstream to Moscow and getting regulations in return? As an autonomous republic with an elected president, it has far more independence than any of the Russian provinces, which are dominated by Moscow through appointed governors. But it’s not exactly independent, even though it maintains an embassy in the Russian capital.

Kalmykia is an unusual place, located on the edge of a distinctly bad neighborhood. While it’s nice to be on the western shore of the Caspian, the location abuts very troubled Dagestan, which is all that separates it from Chechnya. Although I haven’t been to Dagestan or Chechnya, it’s clear Kalmykia is about as different from them as can be. Kalmyks are Mongols, leftover from the days when Genghis Khan overran Russia, and they’re Buddhists, the only such population in Europe. And where Chechnya is mountainous, Kalmykia is wide open plains, steppes, and semi-desert. Wide-open spaces make for a totally different social ethos.

The President, Chess, and Buddhism

Kalmykia’s president, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, is as unusual as the country itself. Despite holding office continuously since 1993, he hasn’t tried to turn himself into a dictator. He’s the head of FIDE, the governing body of world chess. As a consequence of this and of his prominence as president, chess is a hobby of every school kid in the country. There’s even a Palace of Chess, where the world championship match between Anatoly Karpov and Gata Kamsky was held in 1996.

Ilyumzhinov is also a friend of the Dalai Lama. Longtime readers know that I’m not a fan of religion in general, and especially not of religious leaders. But, despite the sordid his- tory of Tibetan Lamas, who ran the country like the feudal kingdom it was before the Chinese invaded, the Dalai Lama seems like a pretty decent type. Although religion and politics (the two things you’re never supposed to talk about in polite company) are his stock in trade, he still seems to get invited to all the more fashionable parties. I suspect that’s partially because he’s scientifically inclined and not a dogmatist. He’s often said that if science proves that Buddhist scriptures are incorrect, the scriptures should be rejected. It’ inconceivable that the pope or the Ayatollah or Pat Robertson or, for that matter, absolutely any other well-known preacher (all of whom would be terrible dinner guests, except for the curiosity factor) would allow such a thought.

The reason openness is so easy for the Dalai Lama is that Buddhism isn’t so much a religion as an ethical system. It concerns itself more with figuring out the right thing to do than doing as you’re told. Of course it has its share of atavisms and superstitions, but were a Martian to visit this planet and try to determine which, if any, religions have some value, he’d have to put Buddhism on the shortlist, if only because it never proselytizes, persecutes, or fights holy wars. I have no embarrassment wearing the bracelet the monks gave me when I visited their monastery outside the capital, Elista.

In any event, there’s plenty of evidence it’s better to have a Buddhist (even a serious one, or maybe, especially a serious one) running a country than a serious Christian or Muslim. And because many Buddhists tend to be overly detached and unworldly, it’s worth noting that Ilyumzhinov is a self-made multimillionaire (as is Alexey Orlov, whose card reads “Russian Federation, Republic of Kalmykia, First Deputy of Prime Minister of the Government, Permanent Representative of the Republic of Kalmykia to the President of the Russian Federation,” with whom I spent more time), apparently having done well in the construction business in Moscow.

The natural assumption (which is especially valid in the Third World) is that everyone in politics is either a thug or a thief, and the direction of their rule is determined by which it is. My impression – and I promise that I never give politicians the benefit of the doubt – is that these guys may be exceptions. If I’m right, Kalmykia is an area of Russia that may do quite well. The place may even avoid ruination by the oil revenues it will soon be getting. (Oil is usually a curse to the country that has it.)

My visit was during “Indian summer” or as it’s called here, grandmother’s summer, or babyaleto – from the Russian words babushka, or grandmother, and leta, or summer. It’s an excellent time to visit, unless you’re the German Army. Kalmykia is only a couple hundred kilometers from Stalingrad (now called Volgograd), which was the site of the ugliest, as well as the most important, battle of World War II – or the Great Patriotic War, as Russians call it. The war was no fun for Kalmykians. The German Army occupied a good bit of the country. Then, after the Red Army reconquered it, Stalin, in a typical fit of megalomaniac paranoia, deported most of the native population to Siberia, for fear they’d join with the Germans. Half of the deported population died from the brutal conditions. And all their horses were stolen by the Red Army – a terrible affront for the descendants of Genghis Khan.

This turned my thoughts to what, if anything, really goes on in people’s heads. How stupid were the Nazis, not taking advantage of the hatred everyone in the USSR (probably including most Russians) felt for Stalin? They managed to turn millions of potential allies into enemies. How stupid were the Reds, diverting huge resources from the war to transporting and slaughtering domestic populations? How stupid were the populations, allowing themselves to be rounded up like cattle? How stupid were the Americans, get- ting involved when they could have let the Nazis and Communists destroy each other? Einstein had it right when he reputedly said that, after hydrogen, stupidity is the most common thing in the universe.