Dwarfing their chairs and stools in the broad hallways of the Polish Ministry of Finance sat fat old women with moustaches. Each of them edged into the halls from the great office doors as though escaping in slow motion. They nibbled on little cakes, gently gossiped, and sipped sweet tea all day long.

They did nothing else. I mean no work at all, ever. They made no pretense.

It took me a long time to get used to them. It was best to pretend that they simply were not there. I once begged the secretary of a high-ranking bureaucrat to help me send a fax to the World Bank. I couldn’t operate the fax machine, and it was an important communication. The finance minister himself cared about what I was doing. The secretary was friendly about it, but my request was risible. She laughed at me. She simply would not work.

I wondered how, in a country with so many comely young women, these old hallway fixtures managed to be so ugly.

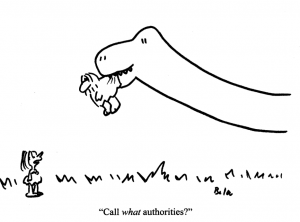

Polish men told me (and my experience did not contradict them) that older Polish women were hideous and fat, with black hairs coming out of unlikely places. Young Polish women were blonde and beautiful. The men had a theory that these old and young women were of two different races; the young ones never had a chance to get old, because the old ones killed and ate them. And that’s why the old ones got so fat. I suppose it did have something to do with their diet. But I digress.

When I moved temporarily from Paris to Warsaw in 1994, it was like moving backwards and sideways in time. Backward because everything seemed to have been built before 1960. Sideways because all the old Polish buildings strove for a dated futurism. Communism had frozen Poland in the past, but it was a past that worshipped socialist progress and the socialist future. The government directed what little bit of

energy, economic growth, and foreign aid the country could muster into futuristic projects. Its ideas about the future itself (at least as expressed in the buildings and trams) were stuck in the first half of the last century, in the form of socialist realism.

By the wa~ foreign aid that came to the East Bloc from capitalist countries, mostly the United States, helped sustain communism. According to my Polish friends, a lot of foreign aid came to Poland in the 1970s. The communists used it for big capital projects.

How disgusting that the Soviet rulers and their puppets, given the chance, decided what every city and building would look like! It’s such a shame, because the Poles were not very good communists at heart. Maybe they wanted to make beautiful things that looked nothing like socialist realism. Maybe they are making such beautiful things now. But in 1994 they were saddled with nearly a half-century of officially constructed blight, and they were just waking up from a long nightmare.

The place was dreary and gray. Everything seemed to be covered by a fine layer of oil. Smooth, old metal parts of heroic fabrication, lightly greased – that was the character of Warsaw. I was shocked to learn that Warsaw was termed the Little Paris of the East Bloc. In the communist years, wealthy Russians loved to vacation in Warsaw. It was, according to my Polish friends, a great escape from the gloom of Russia. I was thinking, my God, how could anyone survive in a place gloomier than Warsaw, in a place so gloomy that Warsaw was the City of Light? Moscow must have really been hell.

The streets of the Polish capital were absurdly wide, and sooty buildings in disrepair squatted across whole blocks. I lived in one such building. Everything in my small, furnished

Powerful men walking around the Ministry carried their own rolls of toilet paper. Twenty- two-year-olds ran vast banking empires. High officials were unable to make simple, obvious decisions.

apartment was old, cheap, and worn. The water was rusty. I was paying a fortune by Polish standards. This was Warsaw’s version of upper-middle-class living.

On a certain date in the late fall (practically a national holiday), the city turned on the heat, centrally supplied in the form of steam. That’s right; they had some kind of central steam factory. When it broke or ran out of fuel, everyone froze. The city did not turn on the heat when winter arrived early and did not delay the heat when winter arrived late, or for warm spells. Once the heat was on, it was on until spring. It wasn’t metered. Nobody paid for it directly. The radiators blasted their moist heat. Windows all over the city were wide open to moderate the temperature. But often, the first day of officially distributed heat was delayed – for financial reasons. People liked to grouse about that.

It’s funny how central steam seems so absurd to me, but I rarely think twice about central electricity. If our own state were less socialistic, I suppose central electricity would also seem absurd. Each house or neighborhood would make its own electricity. One might buy it from competing companies. People get used to the absurdities of central control.

When I talk to friends about limited government, they often scoff and cite road building as an example of how my logic goes too far. They say in mocking tones, “I suppose you think private companies should build the roads.” They think that they have reduced my arguments ad absurdum. Yet there is nothing absurd about private roads. They are common and are usually of excellent quality.

Near the top of a steep road that I often climb by bicycle, I always get a laugh. There’s a sign that reads, “Caution: end of the county-maintained road.” The county wants to avoid any responsibility or liability for the private road beyond the sign. Yes, should you venture beyond this sign, you will see the horror, the abomination of a private road. In fact the county road is rough and cracked, and the private road smooth and beautiful. So I laugh every time.

The trams were a good example of Warsaw’s greasy character. They were all of futuristic burnished metal, and oily. You could acquire a sad affection for the trams. They ran, slowly and cheaply. I took the tram to work at the Ministry of Finance.

I reported directly to the finance minister, who reported directly to the prime minister. All the work at the entire ministry was performed by about 25 people, although it employed hundreds. Communism and the command economy had led to this: out of 100 people, 100 had a job, and five worked.

Of the 25 who did anything in the Ministry of Finance, only two were over 25 years old. One of them was the minister himself. The post-communist government drew him from academia. He was like the professor, and all the 20-somethings were like his students.

The other older person who did any work was a crusty apparatchik who was ready for anything. I liked him. I think he liked me too, because he introduced me to his beautiful 16- year-old daughter. With a wink, he sent me off on lunch dates with her. She was formal and shy. But she certainly was eager to improve her English. “It is just for English,” she would defensively say. We became friends once she realized that I was not going to court her at the behest of her father.

I asked some of the young workers about all the worthless employees, particularly the old ladies in the halls. They told me that most people, after working under the communist regime for more than seven or eight years, could not be reformed. They were hopeless and would have to be carried along for the duration. You couldn’t fire them. That might be unfair and would certainly cause riots and strikes. Inflation would chip away at their incomes. They would become bitter and remain lazy.

From all I saw in Poland, I conclude that, after the great Solidarity movement and the fall of the Wall, there was a revolution affecting the people at the very top of major governmental and government-controlled institutions. They were largely replaced with newly minted college graduates. The rest of the hierarchy was a series of sinecures.

So these young men and women, fresh out of college, some of them just 19 years old, were remaking Poland. (I met the president of the biggest Polish bank. He looked to be about 22 years old.) I was supposed to help them by giving little courses on financial markets and by hanging about and lend- ing a hand. By happy coincidence, they were gearing up to

offer open-market government bonds for the first time since before World War II. I knew about bonds.

But the Poles were burdened not just by the legacy of their communist governments but by their new government too. The director of the international department, for whom I worked, was smart and hard-working. He was also paralyzed by political fear. In one of the first, big, post-communist priva-

On a certain date in the late fall, the city turned on the centrally supplied heat. When it broke, everyone froze. Once the heat was on, it was on until spring.

tizations, the government set the initial public offering price of a bank at a level that turned out to be less than one-tenth of what the market would have paid. It was a scandal causing some very highly placed heads to roll. I believe that the director was terrified. He did not want to make any decisions that might expose him to an accusation of corruption.

The bond issue that I was helping with illustrated the point. Nobody wanted to choose the investment bank to underwrite the offering; the power to choose implied the power to accept bribes. So, unable to reject unlikely candidates, the ministry received and reviewed an excessive number of detailed proposals from investment banks to act as investment advisor and lead manager of the issue. Then the whole decision-making process rotted in a large selection committee with members from several areas of government, business, and academia. Nobody could decide anything, and nobody could be blamed for the eventual decision.

Even the simple, obvious, necessary decision to hire bond counsel to represent Poland proved almost impossible to make. I wrote memos strongly recommending this step. The U.S. Treasury Department, also assisting Poland, wrote extensive letters supporting my recommendation. The director just asked for more memoranda. He passed them up the chain of command (and it didn’t go much higher). Consequently, when I left Poland, this essential but petty decision was sitting on the desk of the minister of finance, who objected that it was not a sufficiently important decision for him to make.

The bond issue made my lessons especially relevant to the bright young bureaucrats. They were used to thinking about capitalism and markets in abstract, academic terms. When they thought about financial. markets in the real world, in Poland, it was too much even for their supple young minds. In particular, they could not believe that some concept called “the market” would set the prices for the bonds. They wanted to know who really set the prices. I would explain the market mechanism again and again. They would nod and agree. Yes, they told me. They understood all about it – supply and demand, market information incorporated in the price, allocation of resources efficiently made through the free choices of millions of people. But who really set the prices? Was it the SEC or the World Bank or maybe the European Community? Or would the Polish government have to set the prices? And who were the secret beneficiaries of the rigged bond issuances?

I feared for the Ministry of Finance. I feared for Poland.

My little report on what I did in the fall of 1994 is pretty dreary.

Command economies make for odd behavior: Old women paid to drink tea. Windows wide open, the heat on full blast Powerful men in business suits walking around the Ministry carrying their own private rolls of toilet paper for the bathrooms. Twenty-two-year-olds running vast banking empires. High officials unable to make obvious, simple decisions.

Yet recent history has obviated my pessimism. I was wrong.

The bond issue was a big hit. And now for years, Poland has been the darling of the post-communist economies. It has experienced rapid, though sporadic, economic growth despite its government’s failure to privatize very large state-owned companies. The growth, of course, has been in sectors where smaller companies were privatized, and in new sectors of activity.

Poland’s total exports increased more than 30% in the first nine months of 2004.* From 1991 to 2005, its GDP grew an average 4%, annually. Its rapid growth has been persistent. In 2005, for example, its industrial product grew 9.2%. In 1999, Poland joined NATO.

From the CIA’s factbook on Poland:+ Life expectancy at birth is now above 74 years. The literacy rate is 99.8%. Exports to the EU are surging. GD~ adjusted for inflation, grew 3.3% in 2005. Unemployment is now high – which I consider to be a great achievement of liberalization and an ingredient of rapid economic growth. And I believe that someda~ mature Polish women will be beautiful.

The obvious lessons from Poland are that some freedom and capitalism are better than none. The less obvious lesson is that very incomplete and corrupt liberalization can still make

They wanted to know who really set the prices. I would explain the market mechanism. They would nod and agree. They understood all about it. But who really set the prices?

huge differences in lives and economies. The forces of freedom and capitalism are not hothouse flowers. They will grow in a little dirt between the cracks. They will flourish in a vacant lot They will set up great forests in a land that demolishes most of its state structure. The Poles, like most humans, seem to be natural capitalists. God bless them.