The period from the fall of the· Western Roman Empire, until approximately the middle of the 11th century, is often known as the Dark Ages. For human liberty, the period was indeed dark. Two changes in political consciousness helped bring an end to the Dark Ages: the growth of feudalism, and the Papal Revolution initiated by Pope Gregory VII.

Submission to Tyranny

The fatalistic tendency of political theorists in the Dark Ages was to view all political power as granted by God and rulers as unaccountable to any human being (although they were accountable to God): rulers were above the law, and everyone else was obliged to obey them. Proper temporal rule seemed of little importance, since the world was going to end in the year 1000, or perhaps in 1033, a thousand years after the death of Jesus.

The king was sacred, and most political theorists in the Dark Ages believed in unlimited submission to government. For example, Archbishop Hincmar of Rheims (approx. 805-881), an important adviser to King Charles the Bald of France, wrote a pair of treatises, De Divortio and De Regis Persona, distinguish- ing a king (who assumed power legitimately and who promoted justice) from a tyrant (who did the opposite). Yet even Hincmar argued that tyrants must be obeyed unquestioningly. When Louis the German invaded France in 858, Hincmar remonstrated him with words from the Psalms: “Thou shalt not touch the Lord’s anointed.”

Kings were considered Christ on earth, and during a coronation, the bishop would gird on the king’s sword, a symbol of the king’s role in fighting the Church’s enemies.

Feudalism

The feeble Western Roman Empire had been conquered by barbarians in the 5th century. After the fall of the Roman Empire, some relatively potent states had arisen, such as Spain under the Visigoths and France under the Carolingian kings. But by the end of the first millennium, Gothic Spain and Charlemagne’s France were distant memories. The essential function of government, providing security against attack, was no longer provided by the employees of a king in a distant capital.

Instead, the lord of the nearest castle and a few knights in his service provided security. That castle was the fortress into which the local community could reheat in case of attack. “All politics is local,” U.S. House Speaker Tip O’Neill would observe a millennium later, and politics was especially local during the feudal age.

Because churches, monasteries, and convents were frequent targets of barbarian attack, they relied heavily on the local lord and his knights for protection. As a result, the church increasingly came under control of the micro-states.

Under feudalism, all ownership of land was based on reciprocal obligation. The farmer received protection from the lord of the castle, and was.obliged to give the lord a share of the farm’s produce. The lord in turn held his land in obligation to some. greater lord. The lesser lord would pay his “rent” by providing military service (a certain number of knights and other fighters for a certain number of days) when the greater lord mustered his forces. These land-based, reciprocal obligations were passed down from one generation to the next. Eventually, the obligations of “vassalage” ran up to the greatest landholders, who owned their land by feudal grant from the king.

Feudal obligations were created by mutual oaths sworn before God. When kings ascended to the throne, they too took feudal oaths, setting forth their obligations to the governed. Reciprocal obligation was the foundation of civil society.

As Glanvill’s famous 1187 treatise on English law explained, when a lord broke his obligations, the vassal was released from feudal service. If a party violated his duties under an oath, and the other party suffered serious harm as a result, the feudal relationship could be dissolved diff ratio (withdrawal of faith).

In “The Medieval World,” historian Friedrich Heer argues that the diffidatio “marked a cardinal point in the political, social, and legal development of Europe. The whole idea of a right of resistance is inherent in this notion of a contract between the governor and the governed, between higher and lower.”

Thus, historian R. Van Ceanegm observes in “The Cambridge History of Medieval Political Thought,” that modern society is founded on “one element … that can be directly traced to feudal origins: the notion that the relation between rulers and citizens is based on a mutual contract, which means that governments have duties as well as rights and that resistance to unlawful rulers who break their contract is legitimate.” Reciprocal feudal obligations “were the historic starting point of the limitation of the monarchy and the constitutional form of government, whose fundamental idea is that governments as well as individuals ought to act under the law.”

The Gregorian Reformation

In the Dark Ages, there was no separation of church and state, and it was the political class, not the priestly class, which held ultimate power in the church. Kings were often the head of the national church, and they appointed the bishops. Many bishops controlled vast feudal domains. The church bureaucracy, with a near-monopoly on literacy, formed the backbone of local government in much of the West; so the power to appoint bishops amounted to the power to control the government.

Some bishops married, and their marital alliances solidified their ties to the royal regim.es. Kings and their courts often made the final decision on disputes over church law and governance. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire,

Kings were considered Christ on earth, and during a coronation, the bishop would gird on the king’s sword, a symbol of the king’s role in fighting the Church’s enemies.

the papacy frequently had to contend, not always successfully, for independence from the Byzantine Emperor, or from closer rulers. By the end of the first millennium, the Holy Roman Empire ran the papacy. The emperor appointed the pope, and deposed him if he stepped out of line.

The Holy Roman Empire was comprised of most of Germany, much of Italy, and a part of France; the Empire claimed to be the successor state to the Western Roman Empire. The name “Holy Roman Empire” was not used until 1254, but a Germanic state ruling much of Italy was far older, and many historians refer to this German-Italian empire as the “Holy Roman Empire,” even when discussing events before 1254.

Beginning in the 11th century, the church began to reassert its independence. In 1059, a papal council declared that the Roman cardinals, not the Holy Roman Emperor, would appoint the pope. “Freedom of the Church” was the slogan. In 1075, Pope St. Gregory VII declared papal supremacy over the church, and further declared the church’s independence from secular control. In a series of Dictatus Papea (Dictates of the Pope), Pope Gregory went even further, asserting the pope’s powers to depose emperors, and to absolve subjects of unjust rulers from their oaths of fealty to the ruler.

Gregory VII started the Investiture Controversy when he declared that no layman (not even the emperor) could invest

-that is, provide the vestments and the authority of office

-a bishop. Unsurprisingly, the monarchs refused to surrender their power·of lay investiture. The result was a series of wars pitting the Holy Roman Empire against the papacy and its allies. Pope Gregory VII announced the deposition of Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, although he did not succeed in forcing Henry off the throne. In 1122, the Vatican and the Holy Roman Empire reached a compromise at the. Concordat of Worms: the Pope would appoint the Italian bishops, and the Holy Roman Emperor would appoint the German ones. Today in China and Vietnam, a new Investiture Controversy is underway. The Communist governments insist that all Catholic bishops must be approved by the government. The Vatican adamantly refuses. At issue is whether the Catholic Church in China and Vietnam will be a church in service of worldwide Catholic belief, or a church whose primary mission is to support a totalitarian government.

Consequences of the Papal Revolution

Pope Gregory VII’s “Papal Revolution” failed in its grand objective of uniting all Christian rulers under the Pope’s leadership and control. Yet the Papal Revolution would change the world, helping to promote an intellectual shift that would eventually make possible the American Revolution. In his wonderful book “Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition,” legal historian Harold Berman summarizes:

The most important consequence of the Papal Revolution was that it introduced into Western history the experience of revolution itself. In contrast to the older view of secular his- tory as a process of decay, there was introduced a dynamic quality, a sense of progress in time, a belief in the reformation of the world. No longer was it assumed that “temporal life” must inevitably deteriorate until the Last Judgment. On the contrary, it was now assumed – for the first time – that progress could be made in this world toward achieving some of the preconditions for salvation in the next.

In addition, the Papal Revolution set off two centuries of conflicts between emperors and popes. The papal propaganda produced what Heer calls “a revolutionary breach of the continuity of European history; the transformation of the popular image of the Christian monarch from a sacred and sacrosanct figure into a diabolical object of execration.”

The Rise of Free Cities

During the wars sparked by the Papal Revolution, various cities revolted against the rule of one party or the other. In France and the Netherlands, towns forcibly asserted their liberties against ruling bishops who were subservient to monarchs; the municipal revolts were typically supported by groups loyal to the papacy. Other towns in Western Europe also demanded their rights, and were given charters, grants, or other recognitions of rights from monarchs. Such rights might include limits on taxation, freedom for serfs who escaped to the town and lived there for a year, freedom of trade, the authority for a town to maintain its own courts and for townspeople not to be tried elsewhere, and freedom from feudal dues. Many of the towns were governed by popular assemblies or by elected councils.

Towns bore responsibility for their own defense, which meant that townsmen had the right to bear arms, and the duty to serve in the town’s militia. The Assize of Arms statute enacted by England’s Henry II in 1181 required all townsmen to bear arms.

In northern Italy, cities such as Genoa and Venice began seeking autonomy or independence from the Holy Roman Empire. Their most important ally was the papacy, which was seeking to establish its own independence from the Holy Roman Emperor, and to expand its influence in Italy. Papal armies often fought in support of the cities. By the end of the 13th century, much of Italy had shaken off the Holy Roman Empire. Many cities, though, objected when the pope imposed his own temporal rule on them, and urban revolts against papal rule became common.

A New View of Legitimate Government

In the conflicts between popes and monarchs, the intellectuals who took the popes’ side argued that a king’s obligation is to see that justice is done; if a king fails to do justice, then he is not a legitimate king. Advocates of this view

By the end of the first millennium, the Holy Roman Empire ran the papacy. The emperor appointed the pope, and deposed him if he stepped out of line.

included Peter Damian (1007-1072, a church reformer), Anselm of Lucca (1036-1086, a bishop allied with Gregory VII), Cardinal Humbert (1000-1061, an adviser to the reforming popes), Bernold of Constance (1050-1100, a monk and historian), Cardinal Deusdedit (1040-1100), Bonizo of Sutri (1045-1090, a bishop and noted polemicist), and Honorius Augustodunensis (1080-1156, a prolific and popular author).

Manegold of Lautenbach, a scholar at a monastery destroyed by the German emperor Henry IV, wrote the treatise Liber Ad Gebehardum arguing that the Pope had the authority to release subjects from their obedience to a ruler, as Pope Gregory VII had done. Manegold analogized a cruel tyrant to a disobedient swineherd who stole his master’s pigs, and who could be removed from his job by the master:

[I]f the king ceases to govern· the kingdom, and begins to act as a tyrant, to destroy justice, to overthrow peace, and to break his faith, the man who has taken the oath is free from it, and the people are entitled to depose the king and to set up another, inasmuch as he has broken the principle upon which their mutual obligation depended.

Compare Manegold’s views with the American Declaration of Independence:

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men … That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government …

Manegold and Thomas Jefferson both claimed that rulers are contractually bound to protect the public good. Rulers who violate their duty thereby ceased to function as rulers; they might be removed, and replaced with others.

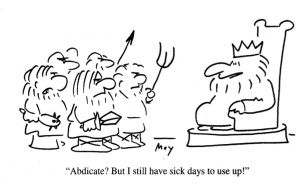

Monarchy had been desacralized. A tyrannical king was no longer “the Lord’s anointed.” Rather, he was nothing more than an employee who could be fired by his employers, the people.

It would take centuries for the feudal and papal principle of contractual government to achieve its greatest fruition in the American Revolution. The Founders knew that their new nation’s religious philosophy had historical roots that were three millennia-old – when in the Exodus, the false god-king Pharaoh was defeated by the true God, who is the only king. The Americans also knew the great debt they owed to the religious philosophies of 16th and 17th century Western European Protestant dissidents.

The Founders may not have known – but we should always remember – that those great Protestant writers, such as John Locke and Algernon Sidney, were building on a foundation of Catholic theology constructed during the Papal Revolution.

Not long after winning independence, the United States of America revamped the British favorite “God Save the King.” The new words reflected the triumph of freedom- lo~ing Christian writers and fighters from Manegold onward:

Our fathers’ God, to thee Author of liberty,

To thee we sing.

Long may our land be bright With freedom’s holy light; Protect us by thy might, Great God our king.

As we fight for liberty at the beginning of the third millennium, we should acknowledge our own debts to the great men of the early second millennium – the men who overturned the false teaching that evil governments exercise authority from God, and who began recovering the principles of liberty and self-government which had been lost since the destruction of the Roman Republic.