During the recent opening session of the modern and gigantic Terminal 4 of Barajas Airport in Madrid – which cost $7.2 billion – chance intervened and turned the event Into a bizarre IllustratIon of Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero’s present-day Spain. While hundreds of passengers missed their flights because of the inaugural ceremonies, the authorities in charge had the brilliant idea of employing acrobats, musicians, and clowns on stilts to cover up the whole mess in a pathetic attempt to entertain the exhausted travelers. It was typical of a country where the ruling politicians try to lessen the calamities they have caused by resorting to “circus marketing” tactics.

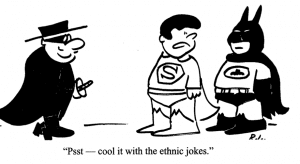

Sickened by the organizational chaos they had to endure, many passengers interpreted the tumblers’ show as a direct provocation, and accused the authorities of trying to make fun of them. Others, long accustomed to being mocked and neglected by public officials, simply resigned themselves to fate and kept silent. One passenger who chose to speak went as far as to compare Zapatero’s Spain to the crazy aircraft in the film “Airplane!”, left in the hands of an ever-smiling inflatable dummy pilot.

One shouldn’t underestimate the Spanish prime minister’s silly smile. His peaceful nature and good temper should not be trusted. His gestures as well as his words are full of trickery and deceit. Yet day by day his political strategy is becoming increasingly clear. It is a vindictive program, stained with the old hatreds left behind by the civil war of the 1930s, and aimed at rewriting Spain’s history by burying the 25 years of exemplary democratic transition after Franco’s death and the signing of the 1978 Constitution. “I am a Red,” he confessed in a moment of weakness. And for once, the words he uttered should be believed.

Whenever a premier admits to a weakness for Mao and the flags and banners of Fidel Castro, it is definitely a bad sign for freedom. Whenever distinctions are drawn between “the Good Guys” (in this case, the Reds) and “the Bad Guys” (those who do not think like Zapatero), it is a terrible omen. Zapatero’s vengeful strategy hinges on reaching agreements with any political group other than the leading opposition party, the conservative Popular Party (PP), for the sole purpose of isolating it politically. In other words, when Zapatero speaks about “the general interest” he is speaking about the interest that remains after excluding the opinions of 10 million center-right voters. This has allowed him to embark on an obstacle-free sectarian policy propelled by the old-fashioned sails of anti-Americanism, Latin-American populism, compliance with the wishes of Islamic nations and – on the domestic front – incautious alliances with provincial nationalists, and negotiations with the Basque separatist group ETA, at whatever price must be paid. In less than two years, the Spain of former Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar, leader of the Popular Party has become unrecognizable.

It all began on March 11, 2004.

M-11 and Its Aftermath

The terrorist attacks of that day, involving the explosion of ten of thirteen bombs placed on four trains in Madrid, took the lives of 190 people. Three days later, the Popular Party – which had been in power for eight consecutive years and for which all polls predicted another clean sweep – lost the national election. In view of Zapatero’s unexpected victory, the Wall Street Journal labeled him “Prime Minister by Accident.”

Almost two years after “the accident,” the Socialist government closed the investigation of the outrage, blaming Islamist terrorists as well as Spain’s involvement in the Iraq war. Even though the authorities lacked hard evidence to confirm al Qa-

Zapatero’s Spain has been compared to the crazy aircraft in the film “Airplane!”, left in the hands of an ever-smiling inflatable dummy pilot.

eda’s participation, in Zapatero’s quarters everybody knew at the time that if they implicated Islamic fundamentalism rather than ETA, they would win the general elections. The blame would fall on Aznar and his involvement in the Islamic-U.S. conflict. Hence, they pointed a recriminating finger at Aznar’s government – which was pursuing the trial of ETA – accusing them of lying and withholding information, and succeed- ed in winning the elections.

Much of the evidence that appeared hours after the attack concerning al Qaeda’s involvement proved to be false and misleading. The investigation was full of incongruities and even today the unknown facts outweigh the known ones. The identity of the mastermind who engineered the terrorist attack is still a mystery as is how it was planned and implemented and what explosives were used. The perpetrators – who supposedly blew themselves up when they were surrounded by security forces in the Leganes district of Madrid, under circumstances that are not clear at all – turned out to be common delinquents of Moroccan nationality. They had merely been paid to carry out the bloody deed. Today, only one person remains in jail for the M-11 attack – a poor devil used as a scapegoat who is expected to be released shortly.

Seasoned journalists who have been following the investigations of M-11 claim that this attack does not bear the al Qaeda stamp. M-11 had little in common with London’s July 7, 2005 subway bombings and New York’s Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. Whenever al Qaeda strikes, it does so with the objective of killing indiscriminately and causing as much damage as possible, regardless of any political calendar. The M-11 attack was aimed at exerting a decisive influence on the electoral results and removing Aznar’s PP from power. Judging by existing police records, the Islamic link is very weak. Also, ordinary criminals keep cropping up in the case, as well as police informants and undercover cops. All this tends to suggest that the terrorist act entailed IInon-fundamentalist logistics.”

Al Qaeda tends to rely on suicidal terrorists, but those who placed the explosive rucksacks on M-11 were Moroccan mercenaries. They detonated the explosives by means of mobile phones and then – under rather shady circumstances, as has been previously stated – apparently committed suicide. Who hired them? Who was the brain behind the M-11 massacre? At this juncture it suits Zapatero’s government that such questions remain unanswered.

Spain’s Incoherent Foreign Policy

The early withdrawal of Spanish troops from Iraq, ordered by Zapatero shortly after reaching power, did not yield the political benefits he was expecting. The decision was consistent with his anti-Americanism and the Socialists’ position when they were in the opposition. Surprisingly enough, however, Zapatero failed to win the support of the Franco-German axis (Chirac and Schroeder), on which he had placed heavy bets, because of the terrible blow the EU suffered when citizens rejected the European Constitution. The defeat of the constitution discredited the anti-American leaders of Europe.

Zapatero made a childish mistake when he prematurely declared his unconditional support for John Kerry during the American presidential elections. The Spanish premier believed that his defiance of the Bush administration would soon be forgotten after Kerry’s victory – which would mark the beginning of a new relationship with the United States. But Bush’s electoral triumph altered his plans and forced him to reconsider his foreign policy in the the Middle East. He abandoned the IIDown with the War” banners and sent reinforcements to the Spanish contingents stationed in Afghanistan and Iraq – behind the back of public opinion. The death of 17 Spanish soldiers in Herat and the image of a Spanish frigate providing backup to an American aircraft carrier in Iraq were two scandals that contributed to the rapid erosion of his credibility.

In spite of his accommodating gestures towards Washing- ton, it has been almost two years since either Bush or Condoleezza Rice has bothered to take his calls. During their latest European tours, neither Bush nor Rice accepted invitations to have their photograph taken with Zapatero. Moreover, the electoral victory of Germany’s Angela Merkel – whom Zapatero had described as a “loser” – and the strengthening of the European leadership of Britain’s Tony Blair – whom Spanish Defense Minister Jose Bono called an “asshole” – further

The identity of the mastermind who engineered the Madrid terrorist attack is still a mystery, as is how it was planned and implemented ssand what explosives were used.

isolated Zapatero, leaving him without any heavyweight EU partners. And explains wh)T, during the latest European budgetary negotiations, Spain lost a substantial part of its economic funding.

Ignored both by the United States and Europe, Zapatero turned to the leaders of the Muslim world, attempting to recover some of his lost prestige by advocating the so-called IIAI- Hance of Civilizations.” His premise is that the best possible way to combat Islamic terrorism is through dialogue and reasonable coexistence – the empty language of multiculturalism and pan-Arabic values. That emptiness was made clear by the violence that erupted after the publication of several caricatures of the prophet Muhammad in a Danish daily newspaper. Instead of solidly defending the principles of free speech and challenging fanaticism, Zapatero called for “dialogue” and demanded respect for the Muslims … closing ranks with

It has been almost two years since either Bush or Condoleezza Rice has bothered to take Zapatero’s calls.

the Turkish prime minister, Recep T. Erdogan, the very man who supported the shameful trial of opposition writer Orhan Pamuk for defending freedom of speech.

Such are the values for which Zapatero stands. While European consulates were going up in flames, the Spanish prime minister sided with Turkish Islamism. Deep down, that is what the Alliance of Civilizations amounts to: a renunciation of the principles of liberty on which the Western world rests. In his view, whenever one is threatened by aggression one must respond with appeasement. If confronted by opprobrium, the thing to do is to pull a stupid smile.

The other feature of Zapatero’s erratic foreign policy is his friendly coexistence with Third World dictatorships. To him, Fidel Castro is an icon, a symbol of resistance in the face of a common enemy: liberal democracy. This is why the Span- ish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Miguel Angel Moratinos, tried to convince the ED to lift the sanctions imposed on Cuba for incarcerating 73 political dissidents. Once again, the Socialists placed their bets on appeasing the tyrant rather than supporting the victims. And in the same way, Zapatero has given political and economic support to the populist doctrines of Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, Argentina’s Nestor Kirchner, and Bolivia’s Evo Morales, so that the ideas of the Cuban dictator might successfully spread throughout South America.

Bowing Before Terrorists

In Spain, ETA’s bombs can still be felt. The government congratulates itself because the terrorists no longer kill as many as they used to but misses the main point: they don’t commit murder because they don’t need to. ETA, which was close to extinction in 2000 after the Socialists and the Conservatives signed the “Agreement for Freedom and against Terrorism,” has recovered its strength thanks to Zapatero and his logic of submission. The Basque terrorist band is now negotiating with the Spanish premier, a political prize in exchange for their bombs – the same ones that have killed over 800 people since the 1960s.

Each time one of ETA’s bombs goes off, instead of vigorously condemning terrorism Zapatero requests patience and otherwise remains silent. Zapatero wants Spaniards to believe that peace is possible for free, when everybody knows that for ETA peace is only possible if the Basque country breaks away from Spain.

This policy of submission and surrender – repeatedly condemned by the families of the victims of Basque terrorism – is aimed at negotiating with ETA a “quick peace,” basically in exchange for legalizing Batasuna, ETA’s political arm, and reducing the prison sentences of the most sanguinary murderers in the history of the terrorist organization. The key to this negotiation process is the state’s General Prosecutor, Candido Conde-Pumpido, who instead of actively fighting terror by resorting to the judiciary has granted ETA all sorts of judicial prerogatives.

Thanks to this, ETA now has seven seats representing their interests in the Basque parliament. Conde-Pumpido was even prepared to allow a meeting to be held at the initiative of Ba- tasuna, which had been declared an illegal party in 2002, until Fernando Grande-Marlaska – a judge who was immune to political pressure – decided to forbid it.

The Socialists’ lack of patience with those who dare defy them is well known. Accordingly, Grande-Marlaska is now looked upon as an obstacle that should be removed, which is what happened to another victim of Zapatero’s sectarian policy: Eduardo Fungairino, the Senior Prosecutor of the National Audience, a major symbol in the antiterrorist fight against ETA. His resignation, brought about by his quarrels and disagreements with Conde-Pumpido, was an obvious sign that Zapatero’s government is negotiating a truce with the Basque terrorist group and that to reach an agreement, all those disobedient prosecutors who refuse to give in to the terrorists’ black- mail must be fired.

Fungairino’s expulsion was a devastating blow to Span- ish civil society because it proved that Zapatero is “purging” the judiciary to make it more docile and malleable, in order to pave an obstacle-free way in his dealings with the terrorists. Instead of dogging terrorists, Spanish prosecutors shorten their prison sentences. Never before had the pro-ETA factions enjoyed so much indulgence from a democratic government, one that does not fight them, or plan to. Such a policy allows them to remain at large without having to resort to weapons.

The Catalan Dilemma

During the last few months, headlines in Spanish newspapers have concentrated on three subjects that are very much related: the Montilla case, Gas Natural’s unfriendly takeover bid for Endesa, and negotiations about the Catalan Statute: a scandal revealing the links between political and economic power groups in Spain. La Caixa – Catalonia’s biggest bank – cancelled a 7 million euro debt contracted by the Catalan Socialist Party (PSC) in the person of its secretary-general, Jose Montilla, who is also minister of industry in Zapatero’s cur-

rent government. The purpose of the operation was to assure the success of the largest takeover bid in the history of Spain, the prospective purchase of the electricity company Endesa by Gas Natural, whose majority shareholder happens to be La Caixa – a transaction in which Montilla, far from being a neutral referee, will undoubtedly wield considerable influence in his capacity as minister of industry.

The political background to this takeover bid is the Catalan Statute, a declaration of “nationhood” driven forward by the same nationalists who are trying to make even medical staff and their patients speak Catalan instead of Spanish (see my article “Damage to Catalonia” at http://www.tcsdaily.com/article.aspx?id=Ol19061). The political alliances that Zapatero has struck with the nationalists are the underlying reasons for his public support of Gas Natural’s takeover bid. His backing is such that he went so far as secretly hiring a private plane to fly iIi the President of the European Commission, Jose Durao Barroso, in order to personally request that he allow the Spanish government a free hand to push the initiative through, unhampered. Just two days after the Spanish government approved the takeover bid, Zapatero had lunch at the residence of the chairman of La Caixa, together with “the cream of Catalan

Zapatero is purging the judiciary to make it more docile and malleable, firing prosecutors who refuse to give in to ETA’s terrorist blackmail.

businessmen” – an unmistakable sign that the aggressive bid had to go through by ·hook or by crook. Zapatero’s involvement in the operation signaled a new golden era for making quick money, for favoritism and corruption, identical to the flourishing conditions that prevailed under the socialist governments of Felipe Gonzalez (1982-1996), when the biggest business contracts were signed in the offices of politicians.

In the wake of the takeover, Zapatero closed a deal regarding the Statute with a Catalan political faction, a deal the exact contents of which the government refuses to make public.

Behind that silly little smile of Zapatero’s dwells a sick mind suffering from political lycanthropy.

When the Popular Party objected to the Statute, on the ground that it would menace Spain’s territorial integrity), Zapatero shut them out of the negotiations.

He thereby provided the Catalan nationalists with the necessary tools to squeeze through a Statute that demands special privileges and fiscal and political powers. Such concessions are a direct breach of the constitution that was agreed upon unanimously by the Spanish political parties in 1978.

After 25 years of democratic transition, advocates of regionalism have found in the person of Zapatero their best possible counterpart across the negotiating table. The success of the transition that followed after Franco’s death was based on the reconciliation of the two Spanish sides that massacred each other during the Civil War. The negotiations over the Catalan Statute are not of that kind, and they have destroyed Zapatero’s public image. According to the latest opinion polls, if presidential elections were to take place at this point, he would lose. He has fallen prey to his own incautiousness, negligence, and irresponsibility, making shameful alliances as well as twisted political agreements for the sole purpose of settling historical debts. Behind that silly little smile of his dwells a sick mind suffering from political lycanthropy. It is the mind of a man who has become an accomplice of terrorism, Islamism, and atavistic nationalism.