This is a crazy world. And I’m not just talking about crazies from the Middle East, who figure that the way to pursue their religion is to hijack airliners and crash them into buildings full of Americans. I’m also talking about plain, commonsensical Americans doing the plainest, most commonsensical thing in the world, investing their money.

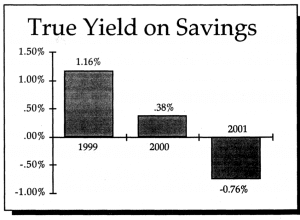

Consider the graph below. It shows the “true yield” of savings – that is, the actual yield an investor can expect on a money market fund after taxes and the effect of inflation have been deducted – at the end of the past two years and on Dec. 7 of this year.*

You’ll note that the true yield for money invested at the end of the past two years is small but positive, but that money invested today actually has a negative yield: Putting money into a money market fund is a sure way to lose. Of course, it would be crazy for anyone to invest when they are guaranteed a loss. But they do, at least for a while.

Actually, the situation is even worse than the graph

*It More specifically, it lists the yield on the Merrill Lynch Ready Assets Trust, less 35% for taxes and the previous year’s change in the Consumer’s Price Index. The true yield varies with each individual’s tax situation.

shows. The money market find yield used there does not yet reflect the cur in interest rates made on Dec. 11, which will surely reduce MMF nominal yields within the next few weeks. Further, my calculation assumes only a 35% tax bite, a very conservative figure, since most investors in MMFs pay a marginal federal tax rate of 36% or more, and, unless they happen to live in one of the handful of states without state or municipal income taxes, they must also pay up to another 13% in taxes to their state and city. In addition, my calculation

accepts the Consumer Price Index as an accurate measure of inflation when, in fact, the CPI is concocted by the government to systematically underestimate inflation.

Here’s the bottom line: Most investors can count on losing about 1%of the purchasing power of the money they put into banks, money market funds, treasury bills, or other short-term, low-risk, interest-bearing investments.

The last time this happened was in the 1970s. To ward off a recession, the Fed lowered interest rates to a point where the true yield was negative. What was the result? It took some time, but people gradually figured out that they were being exploited. And they did what people have always done when government policies to inflate the cur-

Money invested in money market funds today actually has a negative yield: It is a sure way to lose.

rency have the effect of gradually confiscating their savings: They bought gold, silver, and other tangible assets.

The effects were dramatic. Gold shot from $35 to $800. Silver skyrocketed from $1.29 to $50. Inflation rose above the 10% level. The stock market tanked. In an attempt to get inflation under control, the Fed eventually raised interest rates to nearly 20%. The stagflationary recession got worse and worse.

I don’t suggest that those events will occur in exactly the same way in the coming few years. But all the pieces are in place for such a scenario to repeat itself, at least in general terms.

Well, how did this insanity happen?

It happened because the Federal Reserve System, our government’s messianic solution to the business cycle, made it happen. In theory, the Fed was established to stabilize the credit market and control inflation. But during the past year, it has acted as if its purpose were to keep stock prices up. Every time the stock market falls, it cuts interest rates, on the theory that making money cheaper to borrow would do several things: encourage people to borrow to buy stocks; cut the cost of corporate borrowing, thereby increasing corporate profitability; and make more conservative investments less attractive by lowering the returns on everything from bank accounts to bonds.

The problem is that the scheme isn’t working very well, as you can see from the chart below.

The Fed has cut rates no fewer than eleven times this year, yet the Dow is still down9%, the Nasdaq is down 21 %, and every day the economic news seems to get worse: layoffs, bankruptcies, declining consumer confidence, lower profits . . . It’s tough to find any good news on the front page of The Wall Street Journal.

The Fed can still stimulate the stock market, and nearly every cut in interest rates does help revive it some. But this is like giving a very sick patient a strong stimulant: It revives his vital signs, but the disease continues to weaken him.

The Fed’s interest rate cuts have two effects that are lethal for the remainder of the economy. As I’ve already noted, when investors discover that they are losing money on their savings, they gradually move money out of savings and into other assets, thereby reducing the economy’s capital stock.

But as bad as that is, worse follows. Low interest rates are inherently inflationary. Interest is the price of using money. The way you cut the price of something is to increase its supply. If current supply and demand result in money having a price of 5% per year, and you want to lower that price to 4%, the only way you can do so is by creating new money.

The Fed has several methods of doing this, the details of which need not concern us here. What’s important is that the Fed is flooding the system with new money created out of nothing. The increased supply of money cuts interest rates, but it also cuts the value of the dollar. It’s a simple

The Fed can still stimulate the stock market, and nearly every cut in interest rates does help revive it some. But this is like giving a very sick patient a strong stimulant: It revives his vital signs, but the disease continues to weaken him.

matter of supply and demand: If you increase the supply but demand stays the same, the price will drop. In the case of money, that means that its purchasing power will drop. The result is inflation.

Inflation feeds demand for tangible goods. Fine, you might think. But although the government may be able to create new dollars with a printing press.or a computer, it cannot create tangible goods. People realize this, so they start buying up these good.s, hoping to obtain something whose value is not guaranteed to decline. This process further reduces the supply of capital that might otherwise be invested in long-term projects.

Where will it end? I don’t know. but most likely we’ll suffer another serious round of stagflation. A year or two from now, the good times that seemed like·they’d last forever in the 1990s may be only a hazy memory, as people scratch to make a living and to keep alive the hope of a secure future.