I bet against China once. I came to regret it.

It was the first piece I wrote for Liberty, printed in the March 1990 issue. I had moved to Hong Kong the previous September, and was goggle-eyed at the place. It was an odd combination of laissez-faire economics and an ab~enceof democracy. On top of this was the coming handover from Britain to China in 1997, which all the official Hong Kong VOIces assured us would go well. Because my wife was a private banker, I knew that many of the capitalists had foreign passports and assets abroad, and had sent their kids to study In U.S. and Canadian universities. And I thought: Hong Kong is a Potemkin village. The change of sovereignty is not going to turn out well.

The piece was reported on the scene. The logic was good. I can read it today and be convinced by it, if I put the past 16 years out of my mind. Because, of course, I was wrong. Hong Kong’s eight and a half years under Chinese sovereignty have gone much, much better than I imagined.

In 1997, back in Seattle, a local investor gave a talk comparing the development of Russia and China. He was the most renowned international investor in the state of Washing- ton, the CEO of an advisory company known on Wall Street. He had oodles of clients among the Fortune 500. He had led delegations of investors to China and Russia. This man-made the startling statement that he thought Russia was a better bet than China. To be sure, China had had a ten-year head start down the capitalist road, and had gone further than the Russians had. But Russia had undertaken to embrace capitalism and democracy. China had had a chance for that in 1989, and had drawn back. Between economics and politics, China was unbalanced. Russia was balanced, and therefore a better bet.

Another logical argument. I presented it in a newspaper column, and at the end asserted my disagreement, based on a single flippant fact: I had seen lots of modem products made in China, but not one thing on an American store shelf that had been made in Russia.

I still haven’t.

I have not been in China, apart from Hong Kong, since 1999. At that time I accompanied a translator to a university campus in Harbin, went to the student cafeteria, and started buttonholing students to talk politics. I never saw a policeman or an enforcer of any kind, and the students did not act afraid.

The editor of Liberty now asks me to write about the state of freedom in China. It’s not an easy job. China is a big country. I start to read, cognizant that the foreign press covers Beijing, Shanghai, and little else. And the foreign press tends to cover the sorts of things that editors back in America find interesting.

Here is a story from Jan. 6, 2006, which the Seattle Times picked up from the Washington Post:

BEIJING – A businessman who led thousands of investors in a campaign against the government seizure of valuable oil fields in northern China was convicted of organizing illegal protests and sentenced to three years in prison Thursday, relatives said.

The ruling [was] against Feng Bingxian, 59. . . . Feng was one of about 60,000 private investors who developed oil wells in Shaanxi with the blessing of local officials in the mid-1990s. But the officials confiscated the wells in 2003 after they began showing steady profits, and the investors filed a lawsuit against the government last year.

The fight over the wells, said to be worth as much as $850 million, attracted widespread coverage in state media, and Feng became known as an unofficial spokesman for the investors and one of the country’s leading advocates of private- property rights.

Rights are not well defined in China. That is what every- one says. But note also that the man was organizing a group of citizens against the government’s policy. He was a public spokes-

China has opened itself to the world in order to become rich and powerful, and it is visibly on that road. The more that effort succeeds, the more it dooms the dictatorship.

man for them. He got the attention of the Chinese press, and even the American press. This is one tough guy. And the government sentenced him to only three years.

That’s not a free country. But it begins to look like a country where people stand up for themselves.

This, from the New York Times:

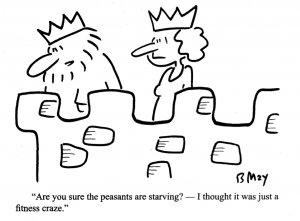

SHANGHAI, Jan. 20 – Land grabs by officials eager to cash in on China’s booming economy are provoking mass unrest in the countryside and amount to a “historic error” that could threaten national stability, Prime Minister Wen Jiabao said in comments published Friday.

His message underscored the increasing urgency of the government’s campaign to curb abuses against peasants and migrant workers, roughly two-thirds of China’s 1.3 billion people, who have relatively little to show for one of the most spectacular economic expansions in history.

Why do they have little to show for it? Foreign investment and development have been mainly in the coastal cities. That is one reason. The Times identified another:

Peasants are not allowed to own the land that they farm and have little say if the government decides to sell it for commercial development. Compensation is assessed according to complex formulas but rarely approaches the market value of the land.

It is notable that some of the most interesting human- rights stories out of China are about property rights. But not all of them. Here is another one, from the Associated Press, Jan. 18,2006:

BEIJING (AP) – China will start taping interrogations of suspects involved in work-related crimes to prevent confessions being extracted through torture, state media reported Thursday. Sound recording will start in March of this year, and video recording in October 2007, the official Xinhua News Agency said …

The move comes amid an unusually frank discussion by state-run media about the use of torture. Xinhua said that Chinese media had repeatedly exposed instances of police using torture to get a confession, which had sparked a public outcry.

A week after that story came one about the closure of Bing Dian (“Freezing Point”), a newspaper supplement, by its owners, the Communist Youth League. Bing Dian had written about lies in China’s schoolbooks and corruption among government officials. It had also published a Taiwan author’s explanation of the spread of democracy in Taiwan.

Chief editor Li Datong posted an essay on the Internet denouncing the closure. According to the Associated Press, he said, “As a professional journalist, stopping the publication of Bing Dian is something I cannot understand, something I cannot accept,” The AP article said Li’s stand was seconded by “Bing Dian fans, who bombarded the Internet with expressions of support for Li and condemnations of the crackdown.”

Another guy with guts. But Bing Dian was reopened shortly after, without Li Datong in the editor’s job.

Then there was the story that got the most attention in the United States: that Google had set up a Chinese website, Google.cn, that would do Internet searches except for certain terms, such as “Dalai Lama” and “human rights.” This was right after Google had defied a U.S. government order for data on its users here. Thus Google extended the middle fin- ger to Washington, D.C., but kowtowed to Beijing.

Google was thoroughly denounced, though not everyone who denounced it acknowledged that the company is not in quite the same legal position in China as it is in the United States. In its defense, Google said that in China every time a search was blocked the user was notified, and that even with the restrictions, the Internet “has been a powerful force for openness and reform in all countries, including China.”

Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates, reached at the capitalists’ conclave in Davos, Switzerland, said about the same thing regarding cooperation by his company with the government of China. It sounded like the crassest sort of corporate apology. But here is one more sto~ this from the Wall Street Journal of Feb. 13, 2006, titled:

Great Firewall

Chinese ·Censors Of Internet Face ‘Hacktivists’ in U.S.

Programs Like Freegate, Built By Expatriate Bill Xia,

Keep the Web World-Wide

Teenager Gets His Wikipedia

This was a story about the hacker underground that has taken on the Commies. Bill Xia, in North Carolina, has developed a program he calls his “red pill,” after the pill of knowledge in the “Matrix” films. Xia’s program, Freegate, allows people in China to bypass their own censors and reach such forbidden s.ites as Wikipedia. Wrote WSJ reporter Geoffrey Fowler:

Even with this extensive censorship, Chinese are getting vast amounts of information electronically that they never would have found a ·decade ago. The growth of the Internet in China … was one reason the authorities, after a week’s silence, ultimately had to acknowledge a disastrous toxic spill in a river late last year.

So Bill Gates was right. Attempts at censorship are a story, and an important one, but the bigger story is how media- smart Chinese – and there are man~ many of them – are getting around it.

What do the professional experts say about freedom in China? There are boatloads of experts, but I’ll offer one in particular, Minxin Pei of the Carnegie Endowment for World Peace. I pick him because he is from China, he went to university there, he has a graduate degree from Harvard, and he is

“Little Bun will not ride on an ox,” grandpa declares. “Little Bun will ride on trains and planes, and life will get better all the time.”

a recognized scholar who writes for Foreign Affairs and such. For these reasons, and because I sat next to him at a conference on China some years ago, with lots of smart people, and he was easily the smartest one in the room.

His work highlights the glass-half-emp~glass-half-full picture of the journalism above. In testimony to the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee on June 7, 2005, Pei noted that many new laws have been passed in China, and that the ranks of lawyers have swelled to 100,000. But he said, “There is no sign to indicate that the Chinese Communist Party is genuinely committed to building a modern legal system.”

The judges, he said, lack independence. Local government appoints them, pays them, and can sack them. If they rule against local authorities, the local authorities can ignore the rulings. Also, judges take bribes. The result of all these things is lack of respect for the written law.

“While a large number of Chinese laws have strong provisions for individual and property rights, in reality such provisions have little meaning because the government, especially local authorities, can ignore them with impunity,” he said.

As for the democracy movement, Pei said in an article in the Financial Times, Jan. 18, 2005, that the government had “decapitated” it by driving most of the leading dissidents into exile. Inside China, the government has tried to co-opt wealth from the new export industries – ranging from clothing to hardware to consumer electronics – by inviting entrepreneurs into the Communist Party. Most have resisted it, but some 30%, have joined.

As for the Par~ Pei wrote in Foreign Polic~Jan.-Feb. 2005, that “regime insiders have effectively privatized the power of the state and use it to advance personal interests.” In a piece in the March-April 2006 Foreign Policy, he is pessimistic about the near-term chances for political pluralism: “To most Western observers, China’s economic success obscures the predatory characteristics of the neo-Leninist state.” Some authoritarian countries – Indonesia, for example – have freed their politics when an economic crisis undermined the government. Writes Pei, “China hasn’t experienced” that crisis yet.” His conclusion is that China’s leaders are buying time by presiding over the world’s most fantastic industrial boom. But the time will run out. You cannot say when, or whether the transition will be peaceful.

Economic development is a kind of anti-ideolog~ a joyful swigging at the bottle of life after the fetid pudding of Mao- ism. One of the fine statements on this is Zhang Yimou’s film, “To Live,” made in China in 1994, which I think of as China’s IIWe the Living.” It is the story of one family from the decadence of the late Nationalist era through the Mao years to the thaw under Deng Xiaoping. It is a long, colorful, sentimental movie whose theme is stated in two scenes, each involving the male lead and a small boy.

The first scene is in the 1950s, during Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward. The man is carrying the bo~ his son, on his back. The boy is tired, and needs to sleep, but his father is heading to a stupid political meeting. The father says to his son:

Our family is like a little chicken. When it grows up, it becomes a goose. And that will tum into a sheep.

And that will tum into an ox.

This is a traditional nursery rhyme, and he is reciting it in a very antitraditional period. The man pauses. One has to watch one’s tongue.

“And the ox?” his son says.

“After the ox is communism,” the father replies. “And then there will be dumplings and meat every day.”

His son is killed by the excesses of stupidity and political fanaticism. But the boy has a sister, and before she dies a grandson is born. They call him Little Bun. At the film’s end, the man and his wife, now elderl~are with Little Bun in their room. He has a box of fluffy chicks, and is told that they will all tum into chickens.

The grandpa’s eyes light up. “And then the chickens will tum into geese,” he says. “And the geese will turn into sheep. And the sheep will turn into oxen.”

“And after the oxen?” the boy says.

Grandpa looks to grandma.

She says, “After the oxen, Little Bun will grow up.”

“I want to ride on an ox’s back,” the boy says, happily. “Little Bun will ride on an ox’s back,” grandma says.

Grandpa, who has been thinking on the theme of growing up, contradicts her:

“Little Bun will not ride on an ox,” he declares. “Little Bun will ride on trains and planes, and life will get better all the time.”

Those are the movie’s final lines. Forget communism.

The film was made by China’s most famous director twelve years ago, and though the movie was banned there, no doubt it has been shown on countless VCRs and DVD players. It expresses the political reality that communism as a belief is dead. What exists is simply the Chinese state. It still has a red flag, and Mao has been put on the paper money. The ruling party is still called the Chinese Communist Party. But in its mixture of authoritarian power and private wealth it is more like the Nationalist Party under Franco or – dare to say it – Chiang Kai-shek.

China is not a free country. Neither was Franco’s Spain or Chiang’s Taiwan. But they became free countries.

Some say the Chinese are so different from Westerners that they do not want political freedom. But the Chinese on Tai- wan wanted it – and, in the 1990s, they got it. The seditious presence of Taiwan, and also of free Hong Kong, are omens for the future of China. Almost nine years after the handover, Hong Kong still has a free press and free elections by opposition parties. Unlike China, it tolerates the Falun Gong. It is still capitalist, and still has the law that the British left. All this, even though it is officially part of China ‘and is garrisoned by mainland soldiers.

Where human-rights activists most want change it appears to be slow, but with other things change is fast. When I lived in Hong Kong in the early 1990s, some businessmen came there from China, but no tourists. The moneychangers did not accept the Chinese yuan. Now they do. During the Chinese New Year holidays in January of this year, so many tourists from· China visited the new Disneyland Hong Kong that management shut the gates – and the mainlanders almost rioted to get access to

The route to the border was a narrow gravel road through the pines, but across the border was a white concrete ribbon laid out for several hundred miles to the metropolis. The contrast with Russia was stark.

Mickey Mouse. They were not the new rich but more ordinary people from Guangdong province who had scraped together enough money for a guided tour.

When I wrote that first piece for Libert)’, Hong Kong had just seen the birth of its first political party. The people of Hong Kong had never stood up against their government. In 1989 they had marched in support of the students at Tiananmen Square, but that was not exactly themselves. Now they have. Two years ago they took to the streets to protest an internal-security law that China wanted – and they stopped the law.

Just a few years ago, when southern China was hit by the new disease SARS, the bureaucracy tried to cover it up. China denied there was an epidemic. News leaked out to the Hong Kong papers anyway, and it was confirmed when a sick man crossed into the territory and checked himself into a hospital and died. Hong Kong jumped into action, as did Taiwan, Canada, and the United States. China was embarrassed. It had shown itself to be backward and stupid, the sort of place where health officials did not listen to physicians, and danger-

Almost nine years after the handover, Hong Kong still has a free press and free elections. It is still capitalist, and still has the law that the British left.

ously sick patients were driven around the capital in taxis to keep them out of the hospitals when the foreigners came. With the bird flu epidemic of 2005, information moved more freely.

It is not just information that moves. Citizens of the People’s Republic now travel to foreign countries. Tens of thousands of Chinese students are studying in North America. Chinese have now discovered eBay, and are making their living off it.

Statistically, China is still poor. In 2005, the average income per person, according to the World Bank, was $1,290. Twenty years earlier, in the same currency, it was $280. In that time, China grew faster than any other country in Asia. It now has an economy larger than Britain’s, though with many more people, and its central bank has foreign-exchange reserves second only to Japan’s.

In June 1999 I entered China overland, from Russia. The crossing point was near Vladivostok, the former home of the Soviet Pacific fleet. Vladivostok was a congeries of shabby buildings, all becoming old. In the surrounding country were private dachas – small wooden cabins, lovingly tended but poor. In the whole place there was almost no visible fresh mon-ey, nothing new.

The route to the border was a narrow gravel road through the pines. Across the no man’s land began a new road, a white concrete ribbon that had been laid out for several hundred miles to the provincial metropolis, Harbin. The Chinese border station was new, and beyond this was a cit)’, much of it new also. I passed a ten-story hotel with a glitzy entranceway, not in very good taste, I thought. It hadn’t opened for business, but a sign in Chinese announced that the opening would be soon. Construction was going on everywhere. The place was messy; there were piles of construction junk, and dirty ponds, and the workers had shabby jackets and bad shoes, but they were at work. Stuff was happening. The contrast with Russia was stark.

Recently I looked at a photo of the skyline of Shanghai. I was there 16 years ago, that year when I wrote my first piece for Liberty. The place has been totally transformed. No Ameri- can city has changed nearly as much in 16 years.

I remember the first thing I ever bought that was labeled “Made in China.” It was a doormat, hand woven from reeds, and I bought it in about 1980. It was the handwork of peasants. Now see what comes from China.

The next thing will be cars.

The democracy movement that was crushed at and around Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, seems like a distant memory. So did the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 as the decades followed – but in 1989, when the liberalizing communist regime decided to pay respects to the murdered leader of that revolution and give him a proper burial, an immense crowd came out. And that was an important event in the transforma- tion of Hungary.

Don’t think the Chinese have forgotten what happened at Tiananmen Square.

They know about the use of information to create political change. At the first full moon in autumn they celebrate one such event. It is the Mid-Autumn Festival. Every child knows it. Centuries ago, the Mongols invaded China and occupied it. The Chinese fomented an insurrection by passing messages to one another in gooey pastries called mooncakes, which the Mongols would not eat. The signal for the rising was for every Chinese to hold up a lantern. They attacked and overthrew the government, and ever since they have celebrated it by eat- ing mooncakes and holding out paper lanterns on the special night.

I believe a change is coming, not because China is so tightly bottled up, but rather the opposite. Tightly bottled-up societies, like Burma or North Korea or the German Democratic Republic, can stay stable for generations. China’s vulnerability is that it is not tightly bottled up. It has opened itself to the world in order to become rich and powerful, and it is visibly on that road. The more that effort succeeds, the more it dooms the dictatorship. Information comes in over the net, over the phone, over faxes, in the mail, and in travelers’ suitcases. People talk. When I was last in China in 1999, I was told, “Now we can say anything we want among our friends.” What they can’t do is publicly challenge the legitimacy of the government.

That will come. I’m betting on it.