Liberty’s intrepid traveler Robert Miller continues his account of the epic bike ride he took through the heart of Europe, along the entire Danube River. For the first part of his libertarian (i.e., self-planned, self-funded, and self-guided) adventures, see here. The third and final part will follow this one.

* * *

The Austrian border was not marked. But we knew we were in Austria when we hit the little town of Niederranna about three miles in: all the vehicle license plates had an A. The terrain, however, changed markedly. A long, deep gorge formed by mountains on both sides squeezed the river. There were few settlements. What a spectacular change from the fields and villages of Bavaria! At a number of points, the impinging mountains became so steep, the shores precluded any room for a trail, and we had to cross to the opposite bank on tiny, dedicated bicycle ferries.

However, before the last crossing — according to our guide — the south bank indicated a trail that went through. So we decided to continue on the south bank . . . ignoring the warning signs that screamed “Achtung!” and “Verboten!” along with other German words alluding to danger, death, and landslides. The bike path doubled as a road, though not much of one and certainly not a through route: downed fall foliage completely obscured the tarmac and punctuated our ride with the constant snap, crackle, and pop of crushed dry leaves. It had no traffic and hugged the narrow space between the Danube and the mountains’ scarp. There was no room for cars passing in opposite directions.

After many miles we reached a serious, giant, unclimbable, stacked concrete barricade with many warning signs announcing active rock fall and a threat to life and limb. The barricade was reinforced by a cyclone fence extending out over the steep river bank, while the inshore side abutted the vertical cliff face. There was no obvious way around. The overcast sky and near freezing temperatures made the impending risk even more ominous. Still, Tina insisted on exploring. On the river side, a tenuous, steep little bank allowed passage if one used some rock-climbing technique while hanging off the overhanging bar of the cyclone fence. After a close inspection, Tina, who always disdained “coloring within the lines,” said, “Let’s try it,” since turning around was about a ten-mile backtrack. I agreed.

We unloaded the bikes and passed gear from one side to the other by having one of us on the near side hanging by one arm from the overhanging fence and passing panniers with the other arm to a recipient on the other side. This required a final little flip of a toss. Then we passed the empty bikes across, a bit more of a cumbersome procedure, but only requiring an arm’s extension because of their length.

So we decided to continue on the south bank, ignoring the warning signs that screamed “Achtung!” and “Verboten!” along with other words alluding to danger, death, and landslides.

Initially, the other side didn’t look bad; it was completely clear. But would we be able to get around the barricade on the far side, not to mention the purported, ongoing avalanche of mountainside?

Ahead, conditions deteriorated. In fact, they got serious. Downed trees lying like pickup sticks had been uprooted by fallen rock slabs and boulders. Entire portions of cliff face dolmens and rock rubble covered the narrow space between mountain and river — and into the river — as far as we could see. But that wasn’t all. The decorticated cliff still glared threateningly. Every forest, understory, critter rumble — even the roar of passing planes — gave us a start. However, someone had already pioneered a sinuous path through the mayhem. After perhaps a kilometer, we reached the closure on the other side of the landslide, where we reversed our sneaky entry procedure. We were home free! As my impish wife says, “We’d gotten away with something.”

Many miles later, outside Mitterkirchen, we caught up with two young Brits and asked how they fared in the gorge landslide. The lads had been unable to skirt the closure and had had to backtrack. Score one for the old folks.

Österreich

In many respects Austria is more German than Germany. Like Germany, after World War II it was partitioned among the Allies, but in 1955 it was united by the Austrian State Treaty, a compact that the USSR agreed to under the condition that Austria declare neutrality. Both Teutonic countries share a strong pacifist streak. Austria has not joined NATO, though it collaborates with the organization. It regularly elects center-right or right-wing governments. Since WWII the conservative People’s Party has dominated government — sometimes in alliance with the far-right Freedom Party, sometimes with the Social Democrats (SPO), and lately with the Greens. Austria and Germany have had an unrequited love relationship ever since they were united under the Holy Roman Empire. That love has been consummated three times but rent asunder as many.

A Catholic Habsburg? No way! Not when Protestant Hohenzollerns, the ruling family of Prussia, were available.

It’s the home of Adolf Schicklgruber, aka Hitler, who — to popular acclaim — reunited the two countries for the third time in 1938. After World War I, with the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the redrawing of borders into smaller entities, Austria sought unification with Germany into a Greater German nation. But according to the Treaty of Versailles, the move was strictly forbidden — in order to avoid the resurgence of a strong Germany. So Austria instead dubbed itself the Republic of German Austria . . . until Hitler forced the issue with his Anschluss. Not having initiated Nazi German aggression, its sense of guilt is tempered by a sense of victimhood: Hitler had after all, invaded, never mind that Austria welcomed him.

A “second reich,” known as the German Confederation, (it’s hard to keep the various attempts at German unification straight) had coalesced in 1815 after Napoleon’s defeat (the official Second Reich had to await Bismarck’s iron fist in 1871). Austria and Prussia led the way by uniting in the loose German Confederation. But since this entity lacked a monarch or central government, it was unstable and didn’t last. Each monarch, Habsburg and Hohenzollern, would no doubt have loved an empire encompassing all Germans under his rule. Prussia strongly objected. A Catholic Habsburg? No way! Not when Protestant Hohenzollerns, the ruling family of Prussia, were available.

Tensions got so hot that Austria and Prussia went to war, with Austria suffering an ignominious defeat. Next year, in 1867, Prussian Chancellor Bismarck — who out-Machiavellied Machiavelli — united Prussia with nearly all the German principalities, free cities, kingdoms, dukedoms, and even republics . . . all except Austria. So, in 1870, after defeating France, Bismarck announced the creation of the German Empire. But why, even after defeating Austria, did he exclude her?

Austria’s sense of guilt is tempered by a sense of victimhood: Hitler had after all, invaded, never mind that Austria welcomed him.

It wasn’t just the religious divisions. After all, Catholic Bavaria had joined the Second Reich, making the new entity about 40% Catholic. But the addition of Catholic Austria would have created a majority Catholic empire, a situation unacceptable to Bismarck. Additionally, after its defeat by Germany in 1866, the Austrian Empire had reconfigured itself into the new Austro-Hungarian Empire, with Hungary playing a nearly equal role in the new entity (more on that later when we pedal into Hungary), a realm that had too many un-German inhabitants — a situation also unacceptable to Bismarck and perhaps a harbinger of later, more explicit racial attitudes, exemplified by terms such as untermenschen. And so the jilted lover remained pining for 71 years, forced by circumstance to cohabit with Magyars, Vlachs, Galicians, Bohemians, Slavs and other folk whom growing familiarity forced it to tolerate if not appreciate.

An Infamous Site

Heading into mid-October, winter rolled out its sleety, wet carpet for us. We awoke to a torrential downpour accompanied by near freezing temperatures. Our destination that day was Mauthausen, the location of a Category III slave labor concentration camp, worst of its kind. Though a common literary trope uses climatic conditions to reflect the emotional reality that a protagonist experiences in the course of a narrative, such as — in this case — awful weather accompanying a visit to a concentration camp, this conceit proved hollow for us. In spite of death camps being existentially tragic, I find survival stories inspiring. Prevailing — even conquering, as in the Treblinka uprising — over extreme adversity is a triumph of the human spirit. I am no doubt influenced by some of the undertakings I’ve pursued in mountaineering, rock climbing, wild water kayaking, life-and-death rescues — not to mention my family’s escape from Castro’s Cuba — in which dire consequences due to poor or unforeseen choices are constant companions. Not that being sent to a death camp was a “choice,” but once there, the condemned were faced with choices that could seal their fate. Some extreme adventurers have said that they only feel truly alive when dancing with death.

What about the gloom-inducing storm? Somewhat like Homer, we welcomed it.

Victor Frankl, a Jewish Austrian Holocaust survivor, alludes to this phenomenon in his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, where he distinguishes the character traits between survivors and mussulmen, as those resigned to death were dubbed. The ironic correlation — that the proximity of death inspires life — even seems to extend one’s lifespan. A January 5, 2019, article in the Times of Israel reports on a study that found Holocaust survivors outliving their peers by seven years: “Lead researcher Dr. Gideon Cohen attributed the unexpected longevity among survivors to a combination of a genetic predisposition that helped them survive the Holocaust and certain resilience characteristics they developed as a result of experiencing Nazi atrocities” (emphasis added). One can survive anything if he steels himself for it. Or, as Homer somewhat hyperbolically puts it in the Odyssey, “A man who has been through bitter experiences and travelled far enjoys even his sufferings after a time.”

But what about the gloom-inducing storm? Somewhat like Homer, we welcomed it. When one is properly equipped, rain and cold are bracing and diverting variations to constant sunshine or heat (though we abhorred head and beam winds). “Properly equipped” . . . Hmm. I’d long ago forsworn “waterproof, breathable fabrics” such as Gore-Tex. Not only do these wear out with use, but in torrential downpours they are useless. Unfortunately, Tina’s breathable slicker had by now failed miserably. She was soaked and shivering uncontrollably as we approached Linz.

Once over the Donau bridge, we entered Linz’s main square, the Hauptplatz, a long rectangle lined with shops, cafes, the old cathedral, and the old rathaus. At its center stands the Trinity Column, the city’s symbol. Hitler considered Linz his home. He planned on retiring there. (Can anyone imagine Hitler as a pensioner? The fact that he could confirms his madness.) My own objective was to find and sample the city’s famous Linzer torte — a pie-shaped shortbread heavy on the butter and egg yolks and filled with hazelnuts, raspberries, and redcurrants — in a suitably natty cafe, Tina was desperate to warm up, dry off, and find an outdoor shop where she could buy a decent rain jacket. After a couple of hot coffees and two servings of the famous pastry, we walked across the square to a Mammut shop where Tina dropped nearly €200 on a bomb-proof, orange alpine rain jacket.

The town of Mauthausen lies right on the banks of the Danube, while the Nazi concentration camp is up on a hill overlooking the town. The inclement weather doubled down, with a high of 51° and continuous rain. We took a taxi up to the camp and followed a self-guided tour. Along with Dachau, it was one of the first Nazi concentration camps, built in 1938. Mauthausen was not an “extermination camp” or camp for Jews, per se. Instead, it was designed as a Category III severe punishment camp for common criminals and enemies of the regime. The camp was organized around a giant granite quarry which was to supply cut stone for Albert Speer’s architectural designs. The regimen was designed to be so brutal that its secondary purpose was to kill inmates, always in extremely gruesome ways. The main camp was headquarters for 100 subcamps scattered nearby in Austria and Germany.

We wondered whether the families now living there knew what had transpired below their foundations and in their backyards now dotted with plastic pools and trampolines.

After the capitulation of France in 1940, 7,200 Spanish Republicans who’d emigrated to France at the conclusion of the Spanish Civil War to escape General Francisco Franco’s victorious regime were arrested and interned in Mauthausen. Records indicate that an unspecified number of Cubans who’d volunteered to fight for the Republic were among the prisoners. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Fulgencio Batista of Cuba declared war on Germany and Italy on December 11, 1941. He broke relations with Vichy France on November 10, 1942. Batista suggested to the United States that it launch a joint US-Latin American invasion of Spain to overthrow Franco and his regime, but nothing came of the plan.

Mauthausen was the last concentration camp to be liberated by the Allies. It is estimated that between 1938 and 1945 about 123,000 people were murdered at all the Mauthausen camps. At liberation, all together they held nearly 85,000 prisoners, many of them Soviet prisoners of war. While the main camp has been preserved as a museum, many of the subcamps have been razed, with single family home subdivisions atop what were once fields of death. We wondered whether the families now living there knew what had transpired below their foundations and in their backyards now dotted with plastic pools and trampolines. As an archaeologist who has performed a handful of environmental impact surveys in the US, I wondered whether these sites had been surveyed or even excavated. I suspected either cursorily or probably not.

Being a refugee from Castro’s Cuba — which in no way compares to the Holocaust and gulag events — I found that a visit to one of these sites reinforced my perception that my family’s experience is a thread in a larger narrative of incredible events. Pundits — philosophers, historians, theologians, and many others — have struggled to explain what they term man’s inhumanity to man. Most explanations are based on the premise of two reifications of abstract concepts: good and evil. Do these really exist? In the same way that a tree exists? These terms are religiously — or even solipsistically — based, lacking any convincing explanation. The best explanation I have comes from sociobiology, which is a fusion of psychology and evolutionary biology, emphasizing the survival value of having a moral sense, whatever it may be. Man’s moral sense is a product of evolution, determined by its survival value. And it continues to evolve. . . . Unfortunately, even Hitler and Stalin had a moral sense of some kind; they thought, amid their atrocities, that they were doing “good.”

Of Wine, Wien, Wenus and Celts

After the morning’s tour of Mauthausen, we continued on to Mitterkirchen, only 26 kilometers distant, but a thousand parsecs of reality away. The weather did not improve. Mitterkirchen is barely a village. We stayed at a farm B&B specializing in pear products . . . for over 250 years. Their Landbirnen Most (pear cider) is an award winner, and with a 6.5% alcohol content goes down swimmingly.

Man’s moral sense is a product of evolution, determined by its survival value. And it continues to evolve.

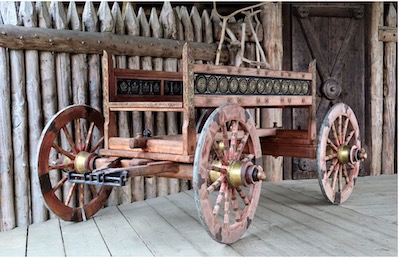

One hundred yards away sits Keltenhof, a reconstructed Celtic village dating from AD 700 that is open for touring. The site was discovered in 1980 and took nine years to excavate fully. Over 80 burials and 900 items were unearthed. The site is unique in that, after excavations were completed, the village was completely reconstructed using replicas of the original tools and materials. Not only is it exceptionally well executed, but it also has instructional, hands-on workshops in carpentry, pottery, jewelry, and metallurgy to help visitors appreciate life in Austria back then. The village’s raison d’être and source of wealth were its salt deposits, which were refined and sold. Its “mayor” was a woman, inferred from her high-status burial mound — including a beautifully crafted wagon — and finely fashioned home.

Keltenhof is notable for its unusual and instructive approach to archaeology — in contrast to most archaeology in the US, where sites are seldom fully excavated, leaving some remains to be excavated in the future when new techniques, theories, and approaches might shed additional light on past lifeways and populations. However, only experts (in general) benefit from this methodology. The Austrian approach in Keltenhof popularizes past lifeways in ways that only a full reconstruction and workshops can accomplish. It is a method that widely popularizes the discoveries of archaeology, as opposed to consigning them to technical journals or even such media as National Geographic.

After riding through more fields, farms, and forests all along dedicated bike paths, we entered a section where the Danube gets squeezed by hills, until Persenbeug, which is located on a flat peninsula created by a river meander. It’s the site of Austria’s first hydropower dam, located right under an imposing Habsburg castle, and was once one of the most important shipbuilding sites on the river. By now, the Danube was becoming a wide inland sea — driven by a decent current, at that — with large ships, barges, and Viking tour boats constantly on the move. “Seaside” beach resorts with palapa-studded strands made their first appearance (and would become more common downstream from Hungary). Restaurants offering seafood, er, river food, carp, catfish, pike, sturgeon, salmon, trout, and many other species were appearing as menu and traditional dish mainstays, often accompanied with chips (French fries) or stewed with paprika and onions.

We overnighted in Melk, cradle of the Austrian nation, and dominated by its monumental hilltop castle, now the Stift Benedictine Abbey, an epitome of the Austrian baroque. The princely Babenberg family, Austria’s first ruling dynasty (and immediate precursors to the Habsburgs), moved to Melk in 976 and made it the capital of the Ostmark, the southeastern borderlands of the Holy Roman Empire. The Ostmark was intended to be a border state between Bavaria and the barbarian Huns, aka Magyars, in Hungary. By 1089 it became apparent that the Huns did not seek further expansion, so the Babenberg Margrave Leopold II donated his castle to the Benedictines (in spite of not being short of feuds and battles with other groups). When the capital of the Holy Roman Empire moved to Vienna in 1156, the Ostmark acquired its modern name, Österreich, or eastern empire. The present building was built in 1702, and included Imperial quarters to accommodate the emperor, who would always overnight at the abbey when visiting the western parts of his empire. The abbey’s library holds a priceless collection of medieval manuscripts.

Every evening I would note the day’s ride and events in my journal. My notes for October 9 are exuberant: “Incomparable Austria! This route is an ADDer’s kaleidoscope. As Julie Andrews declared in The Sound of Music, yes, these hills are alive.” We’d entered the Wachau, Austria’s prime wine region. High hillsides, making for roller-coaster riding, dotted with timeless, cute-as-cuckoo-clock medieval villages — each one a treasure lined with cafes and wine shops — and covered in vineyards. These Stairways to Heaven, as they are called, are terraced top to bottom. The grapes were (over)ripe. We gorged on as many as we dared.

But best of all . . . the village of Willendorf, site of one of archaeology’s most famous — and iconic — discoveries, the Venus of Willendorf or, as German speakers pronounce it, the Wenus of Villendorf. It came upon us in complete surprise. I was flooded with memories of my 1968 introductory archaeology course, the class that sealed my major. As Dr. Robert Euler, my professor, had declared, “The discovery in 1908 of the Venus of Willendorf, is what put the romance in archaeology.” Radiocarbon dated at 25,000–30,000 years old, it is one of the oldest and most famous surviving works of art from the Upper Paleolithic. A tiny, single-purpose museum 50 feet offroute displayed a replica of the Venus. The original was moved to the Natural History Museum in Vienna. Ignoring my usual obsession with adding weight to my kit, I bought an exact replica.

That night in Krems we lodged in a youth hostel, forced to sleep in bunk beds and share personal space with strangers. Not our usual B&B or hotel routine, but for a variety of reasons, the only lodging we could find. It was an unusual experience. All night we were disturbed by noises in an adjacent room. The next morning at breakfast, we discovered the cause. A beautiful young woman, accompanied by a young man, could not control her severe Tourette’s Syndrome. Her head twitched spasmodically, her hands flew up unpredictably, and her vocalizations — in German, so we couldn’t tell whether they were profanities — erupted loudly and at random. Her companion helped her eat. We’d never experienced such a display and wondered how she could ever get any relaxation, much less sleep. Her eruptions occurred nearly once every minute, or so it seemed. We were not aware the condition could be so debilitating and were deeply moved by her distress. Her companion must have loved her profoundly.

Perhaps, as some historians have speculated, Kriemhild murdered Attila. He died on his wedding night from a “nose bleed,” after a drunken orgy.

The following day dawned cold and cloudy, with a daytime low of 33°. At least it was windless. But it didn’t stop a group of animated Poles on an ebike outing led by a Dutch outfitter from savoring what to them must have been a warmer and more boutique vacation than mid-October on the Baltic. They were lunching — beer, goulash, beer, sausages, and more beer — at an isolated café next door to Austria’s first, only, and never completed nuclear power plant. Voters nixed it in a referendum in 1979.

Tulln, our last stop before Vienna, was Austria’s capital for 67 years, between 1089 and 1156. After leaving Melk, the Babenbergs settled in Tulln before moving on to Vienna and making it Austria’s capital. However, the Babenberg’s confidence in the Huns’ peaceful intentions had once before been shattered, back in 453. The Song of the Nibelungs, a German epic written around 1200, extols the meeting that took place in Tulln between Attila the Hun and Kriemhild, the widow of Siegfried Babenberg in 453. A beautiful, multistatued — exquisitely detailed — sculpture next to the Danube commemorates the troth. The couple traveled from Tulln to their wedding in Vienna. It was a harbinger of the more than 1,200-year-later Austro-Hungarian alliance. Never mind the further 500-year incursions from the Huns into Europe following Attila’s marriage to a Babenberg. Perhaps, as some historians have speculated, Kriemhild murdered Attila. He died on his wedding night from a “nose bleed,” after a drunken orgy.

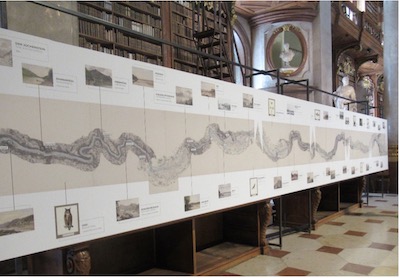

Now we too headed for Vienna. It was an easy ride along the Danube’s levee. We entered Vienna’s suburbs on the north bank, then crossed over directly to the city center. Unlike Budapest, Vienna distrusts the Danube. Every winter the river would flood an area up to six kilometers wide, and onto an even wider expanse downstream. During the 1860s the Habsburg monarchy decided to tame the river, not just for flood control but also to facilitate navigation. As a first step, Emperor Franz Josef commissioned the now-famous 44-meter-long Pasetti map of the Danube within his realm. An exact reproduction of the original was on display at the Imperial Library, an exquisitely wood-paneled, baroque repository with over two million rare collections going back to the 4th century. Over the course of 25 years and with the help of 100,000 laborers the Danube was straitjacketed into two giant concrete-lined channels through outer Vienna.

At the exurbs I teared up at the realization that I was finally in magical Vienna — capital of the Habsburg Empire, Austria-Hungary, and cultural capital of central Europe. When we reached the inner ring road the sentiment became sublime. Tina and I divide up duties for these outings. I organize the itinerary — route, logistics, daily mileage, navigation, and such. Tina researches and books our lodging, usually one to three days in advance. For Vienna, she outdid herself: a fully furnished apartment in the Judenplatz (the old Jewish Quarter), smack in the center of old Vienna and across the alley from Mozart’s house, atop one of Vienna’s finest restaurants (which has been brewing its own beer for years) for less than €100 a night. We stayed four days.

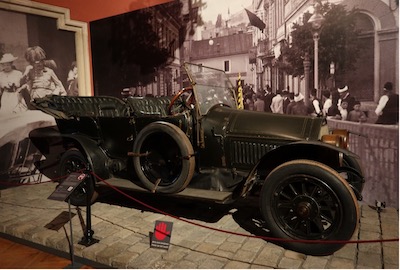

Next morning we made a beeline to the Imperial, er, Austrian War Museum to see the Gräf and Stift double Phaethon in which Archduke Francis Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated. Only a single velvet cordon and about two feet separate it from viewers. I was tempted to touch it, but my inner German held me back. The uniform he was murdered in, with the bullet hole intact, is a few feet away, within a glass enclosure. It was the shot that changed the world. Gavrilo Princip, a 19-year-old Serb, sought the independence of Slavs from Austria in a federation to be called Yugoslavia, or south Slavia, which came to be, existed, and no longer exists.

The assassination took place in Sarajevo, the largest city in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Immediately afterward, in spite of a mixed population of Muslims (35%), Roman Catholics (27%), and Serbian Orthodox (24%), huge anti-Serb riots broke out. Emperor Franz Josef was 84 years old. Young Bosnia and the Black Hand, secret organizations with which Princip was allied, thought that killing the heir to the throne would cause a crisis that might benefit their cause. They got more than they bargained for . . . but they did get a Yugoslavia in 1918.

The uniform he was murdered in, with the bullet hole intact, is a few feet away, within a glass enclosure. It was the shot that changed the world.

Bitter cold and rain the next day. Still, we walked the streets of Vienna. The origin of the name — Wien in German — is contested. Various theories ascribe it to various Germanic and Celtic languages. But any way you look at it, Wiener schnitzel has nothing to do with hot dogs. It’s breaded veal, pork, venison, or chicken, Vienna style.

Sacher torte, another Viennese specialty first concocted at the Sacher cafe in 1832, is totally unlike Linzer torte. The former is nearly 100% chocolate (or so it seemed), while the latter has zero chocolate. We were headed to a special Vienna Philharmonic performance at the Wiener Musikverein of popular Mozart arias, single movements, and overtures, a program in the style of “musical academies,” as concerts were known in Mozart’s time . . . with a Strauss finale. But first, a stop at the Sacher cafe for Sacher torte and coffee. To our surprise, the queue to get in was long. Still, the cafe maintained standards and decorum — including waiters with forearm-draped white serviettes — not rushing the clientele, something we now hoped for, as the wait had squeezed our time for getting to the concert.

The Musikverein is a neoclassical masterpiece built in 1870. Its Great Hall has a long, tall and narrow shoebox shape with perfect acoustics. Though it holds 1,744 seats, it seemed small and intimate, a sensation no doubt emphasized by the light covid attendance, which netted us front-row balcony seats. For the night’s performance the orchestra was kitted out in 1700s period costumes complete with powdered wigs, as were the two soloists. After a few pieces from The Magic Flute, The Marriage of Figaro, others I didn’t recognize, and some vocal acrobatics showcasing the diva’s range (which elicited a standing ovation), the whole was topped by the finest rendition I’ve ever heard of Strauss’ The Blue Danube, with movements and codas underscored in a very Germanic cadence that was almost staccato — perfect for punctuating direction changes when dancing a waltz. It was a fitting climax to our Danube bike ride.

But then, after vigorous applause, the orchestra returned for an encore, Strauss’ Radetzky March, a tune I’d never heard before. In no time the audience began clapping to the beat. Not knowing that the clapping was traditional, I marveled at such unrestrained, emotional exuberance coming from a Germanic people. The enthusiasm was so uninhibited and sincere that the orchestra conductor turned around and began conducting the audience: lento, fortissimo, piano, etc. Ofttimes during concerts a band urges the audience to sing, clap or keep time. This orchestra did not. But anyway, the audience joined in. I happily participated.

For the night’s performance the orchestra was kitted out in 1700s period costumes complete with powdered wigs, as were the two soloists.

On our last day in Vienna we toured the surroundings of the Hofburg, the Imperial Palace. They make Buckingham Palace look like a log cabin. One building held Franz Josef’s personal art collection: works by Velasquez, Rembrandt, Breugel, Caravaggio, Vermeer, Titian, and Tintoretto, among others. He later turned the collection into the Kunsthistorisches museum in order to share the collection with the public.

Hainburg, our last biking destination in Austria, was 60 km away. It was a cold but sunny day as we rode along the Danube’s levee through Danube National Park. After all the city hubbub, we welcomed the solitude. For many centuries Hainburg was the most easterly salient of the Holy Roman Empire, literally the point where east met west. The city was extensively fortified in the 15th century with 2.5 km of walls, three city gates, and 15 defensive towers. These defenses still stand. They were only breached in 1683 when the Turkish army advanced on Vienna to lay siege and conquer it — a siege that failed and proved the Ottomans’ undoing and the start of their empire’s decline. While Hainburg today has only about 6,000 residents, the victorious Turks massacred 8,500 in 1683, a tragedy exacerbated by the city gates opening in, as opposed to out. The jamming crowd attempting to escape prevented the gates from opening.

But we were imminently at another gate, the gates of Hungary, a land the Ottomans did conquer, and this travelogue’s next installment.