In the fall of 2021 and the spring of 2022 Liberty contributor Robert H. Miller and his wife traveled the length of the Danube from its source in the Black Forest of Germany to its delta on the Black Sea, a distance of 1,860 miles, by bicycle. What follows is the first part of his story of that trip, presented in a country-by-country format. Part two, on Austria, is available here.

Click on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danube for an overview of the extent of Europe’s second largest river.

* * *

Dateline Osijek, Croatia, April 22, 2022: Sharing cigarettes and a beer, our hostess at the modest pension we’d booked related the following anecdote:

“Two, perhaps three Januarys ago, I received a phone call from Germany. The caller wished to book a room for a party of three on the following July 9. He said they’d arrive at 5:15 pm.” With such a precise ETA, she assumed they’d arrive by train or bus . . . except that there was no scheduled public transport anywhere near that time.

The party of three — all males, aged 72, 73, and 77 — arrived by bike at 5:00 pm on the date appointed. Embarrassed at arriving early, they waited outside the pension’s door for 15 minutes before knocking.

Our hostess threw her hands up in the air and exclaimed, “Only Germans can predict the exact date and time, seven months in advance, for arrival on a bike trip, and then awkwardly dilly dally for 15 minutes for the sake of Teutonic precision. Hell, these are the Balkans!”

* * *

Call it the Tetrarchico Galerium (as the Romans did), or the eastern reach of the Holy Roman Empire, or of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Even Habsburgia, or the Balkans? Or maybe just Central Europe?

Whatever one chooses to call this sprawling southeastern European area, the Danube is its only unifying geographical feature, crossing eight of its constituent countries. So, following author Simon Winder’s example, I will refer to it as Danubia, an area that encompasses (or has encompassed) all or parts of Germany, Austria, Czechia, Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Albania, Greece, North Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro (and even more if one chooses to be historically inclusive).

Danubia’s size and shape have varied according to the whims of its rulers, most of whom were inbred, self-centered incompetents.

Like the blob in the 1958 Steve McQueen film, Danubia is shapeless and fickle, expanding or contracting unpredictably. It has no natural boundaries but is vaguely centered on Hungary. Though the Black Sea seems to form an eastern boundary, it constitutes no constraining border: vast, endless plains stretch east to Asia and north to the Baltics. Not even the Carpathians offered any sort of obstacle to Slavic, Turkic and Mongol hordes. At least on the west and northwest the Alps present formidable barriers. To the south, the Mediterranean is the limit; but in between, delicious yet toxic morsels bordering the Adriatic have tempted countless conquerors who occasionally took bites — inevitably triggering indigestion.

Danubia’s size and shape have varied according to the whims of its rulers, most of whom were inbred, self-centered incompetents — one even refused to open his mail — concerned only with status, ritual, and protocol. Petty local grievances among the many resident language and ethnic groups have threatened whatever cohesion it ever temporarily achieved. Fission (freedom now!) or fusion (protection please!) also played a big part. And finally, Ottoman incursions on its eastern and southern flanks led to unpredictable contractions inevitably followed by counterexpansions — in repeating cycles.

Throughout its many incarnations Danubia has consisted of a deeply disturbing jigsaw of political entities (hundreds by the later 15th century): principalities, margraves, bishoprics, kingdoms, duchies, free imperial cities, and tiny and not so tiny independent enclaves (some run by nuns) — all held together by various emperors. This tenuous balance was rent asunder in 1918 when the victors of WWI carved the empire into what they determined to be logical nations. Yet the boundaries drawn by these well-meaning elites — using some sort of Escherian logic — satisfied few.

After WWII and again during the wars of Yugoslav secession in the 1990s, nationalists, autocrats, and concerned do-gooders repeatedly fiddled with the frontiers. Today, revanchists still pine for “lost” territory. To the fore stand German speakers in the South Tyrol who want to rejoin Austria, Serbians pining for Kosovo, Romanians and Hungarians arguing over Transylvania, Macedonians out for bits of Greece. Bulgaria, Serbia, and Albania object to Turkey’s foothold west of the Bosporus. More recently, Russia has extended its suzerainty over Belarus, Georgia, and Moldova (claimed by Romania . . . don’t mention Bessarabia or Bucovina . . .). Now Ukraine is on the receiving end of Putin’s pounding.

All of the linguistic, ethnic, and religious groups have some sort of historical beef with each other. Many make no sense at all.

Balkanization: the division of an entity into smaller, mutually hostile groups. The Balkans are the poster child for this unique concept, hence the coining of the term. Altogether there are 88 ethnicities, religions, and distinct languages, live, dead, and dialectical in the Balkans . . . only slightly more than there are gender pronouns in English (78 at present). Although scholars disagree on the exact numbers, there are about 35 distinct languages including dialects, and about the same number of ethnicities in the area, with an additional 13 extinct tongues. Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Eastern Orthodoxy — with as many as six distinct branches — Islam, and Judaism are the main religions. Not to imply that every category is mutually exclusive: ethnicity, language, and religion often overlap, making for even more tiny categories, e.g. bilingual Catholic Swabian Hungarians, Orthodox ethnic Turks in Bulgaria, etc.

All of the linguistic, ethnic, and religious groups have some sort of historical beef with each other. Some of the beefs are still raw, some have burnt to a crisp (but still attract nibblers), and some just simmer under the surface. Many make no sense at all. Nevill Forbes, in a classic 1915 study of the Balkans, writes, “The Serbs and the Croats were, as regards race and language, originally one people, the two names having merely geographical signification.” Robert D. Kaplan, quoting Forbes in Balkan Ghosts, adds, “Were it not for religion [one is Catholic, the other Orthodox], there would be little basis for Serb-Croat enmity.” Even the Croat Ustashas and Serbian Chetniks hated each other but had similar politico-economic ideologies. Both peoples, mixed in today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina, are ready to barbecue each other.

Cycles of Conquest

EuroVelo 6, Europe’s most popular cycling route, begins on the Atlantic coast of France, crosses Switzerland, descends to the Danube’s source in the Black Forest, and follows the Danube all the way to the Black Sea. At 1,771 miles, the Danube is Europe’s second longest river (after the Volga). Much of the route along the Danube is paved, dedicated, and downhill (or so we assumed). The altitude at its start is 2,224 feet, ostensibly providing a biking gradient of approximately 1.25 feet per mile. It is well marked most of the way, with decent to excellent accommodations . . . though Romania and Bulgaria lack signage, and lodging can be an adventure. The section between Vienna and Budapest attracts more cruisers — on both bikes and boats — than any other portion. Long distance trippers are outnumbered by old people on ebikes (battery assisted bikes) who when effortlessly passing us always elicited a friendly “Get a real bike!” admonition from me.

My wife Tina and I are addicted to crossing countries through the immersive medium of bicycling. Though we’d previously crossed Germany north to south along the old West German-East German frontier, we’d never crossed Austria, much less visited Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, or Bulgaria. Biking the Danube seemed the perfect route for such an adventure — in spite of (or because of) its checkered history.

This is an ambitious travelogue. I will not attempt the impossible task of recounting Danubia’s history. It is an endless sequence of non sequitur albeit fascinating anecdotes whose trajectories abruptly stop or lead nowhere, as if attempting to trace the course of cracks in fractured tempered glass. I’ll leave that to Dame Rebecca West whose Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, at 1,100 pages in two volumes covers only what became Yugoslavia, and only up to WWII. The book is exhaustive, and is generally considered one of the most important books about Eastern Europe.

It was touch-and-go. We scheduled the first half of the trip, from source to Budapest — at 1,000 miles — for September-October 2021 and began preparations in June. The second half we planned for the following spring, April and May. But covid restrictions, ranging from country closures to vaccine and booster requirements, along with mask, social distancing, and business closures and restrictions were still in place. We took a gamble. Germany was the key. If it opened up to Americans, we figured we could sneak into Austria, Slovakia, and Hungary by bike regardless of whether they allowed foreigners in or not.

Danubia’s history is an endless sequence of non sequitur albeit fascinating anecdotes whose trajectories abruptly stop or lead nowhere, as if attempting to trace the course of cracks in fractured tempered glass.

And then the Delta variant hit. Two weeks before departure, new EU restrictions were announced. Germany remained open to Americans, but with draconian protocols, including pre-flight molecular tests, which at that time cost $200 each for quick results. Hungary remained closed.

We flew into Frankfurt and booked a room close to the train station in a trendy, hip hotel in the red-light district overlooking “needle park,” where drug addicts shot up and slept rough. Occasionally, one with a bucket would make the rounds picking up discarded needles. Police patrolled but ignored the goings on, while the untervolk mostly kept to themselves but engaged in the occasional inter ipsi scuffle.

We found adherence to covid mandates refreshingly un-German . . . mostly. Even on the plane — and in the airport — exposed noses weren’t reprimanded. No one requested our test results, and our taxi driver went maskless. Hotel staff did not demand masks, only proof of vaccination. That night we were hornswoggled onto a tightly packed rooftop rave — a classic superspreader event. Free wine and techno blast music. A Millennial crowd. I sidled up to a very exotic looking Latina and asked if she spoke Spanish. Yes! A Colombian, with a similar accent to Cuban Spanish, my native language. She confessed that she’d married a German so she wouldn’t have to work. Doesn’t cook, no kids; just wants to stay home and be supported. Lives on Uber Eats and such. Her dad hates Germans, says they’re all Nazis. We’d had enough. We went to bed.

The following day we kitted up and tested our bikes by riding to the train station to buy tickets for Donaueschingen, the little town at the Danube’s source. Still jetlagged, exhausted after 20 hours on airplanes, lugging bike boxes and giant duffels, and about as adept at German as I am at ballet, I interpreted the German word for train station, hauptbahnhof, as “huffandpuff,” a rendition that stuck with us. That night, another rooftop rave — this time called a “spice”: a “queer” event. Exotically dressed people came into the lobby, registered, and went up. I quipped that it looked like so much fun that I was tempted to become gay for a day. One attendee overheard me and retorted, “Every day is a good day to be gay!”

Germany: The Schwarzwald

On September 19 we took the Deutsche Bahn to Donaueschingen, deep in the Schwarzwald, the Black Forest. The Forest has always had an ominous ring to me, perhaps from association with the dark folk tales of the Brothers Grimm. It is a mountainous plateau in southwest Germany, bordering France. Known for its dense, evergreen forests and picturesque villages, it’s also renowned for the cuckoo clocks produced in the region since the 1700s. The stork, that fabled charismatic bird reputed to bring good luck and, metaphorically — at least in Europe — babies (a subset of the luck bit relating to conception), is ubiquitous. We saw many stork nests atop roofs, chimneys and even purpose-built on poles, one of which had a pair of nestlings . . . confirming that they actually do bring babies.

Our hostess at the farm B&B laughed when we showed her our vaccination cards and dismissed the whole subject with a disgusted snort and an impatient wave of the hand. On the following day we set out looking for the Danube’s source. It was not an easy task, and a location not completely agreed upon.

In AD 5, the Romans recognized a spring, the Donauquelle, in what was to become downtown Donaueschingen, as the Danube’s source. This spring has been commemorated by a striking circular fountain with a group of statues above the pool, depicting “the mother Baar” — a plateau in the Black Forest — showing her “daughter,” the young Danube, the way. Later, the confluence of the Breg and the Brigach streams were recognized as the source. Today, using modern geographical and hydrological principles, the Breg, being longer and having a bigger water flow than the Brigach, is the contender for the Danube’s source.

Our two guidebooks took separate approaches to the start of the bike ride. One, a British Cicerone guide, begins the bike trail at Furtwagen, where the Breg begins. The other, a German Bikeline guide, starts the trail at the junction of the two streams just outside Donaueschingen below the Donauquelle. We chose to begin at the confluence. Still, it took us half a day to find the junction. Road construction, along with some rechanneling of the Breg, had rerouted the bike path. Though the route is well-marked, our ignorance of the word umleitung — detour — caused further confusion. We pedaled around in circles for a while before actually heading downstream.

Twenty-seven kilometers after its source, the Danube disappears. Coursing over a porous limestone undersurface, the river goes underground during the drier summer months of the year. After twelve kilometers, the Danube magically resurfaces.

The Schwarzwald has always had an ominous ring to me, perhaps from association with the dark folk tales of the Brothers Grimm.

On our second day we overnighted in Sigmaringen, ancestral home and castle of the Hohenzollerns, the family that provided the kings of Prussia, the Kaisers of Germany, the kings of Romania (Carol I & II and Michael), and, though not as exalted a personage, Joseph, a curious character who joined us for a currywurst mit pommes lunch in Beuron. Joseph’s eyes wandered, and he was given to impromptu tears. His English was good, and he was impeccably, albeit modestly dressed, with manicured fingernails. He said he’d dedicated his life to God. Occasionally he’d ask if he talked too much. Besides being a Hohenzollern, he claimed that he was a scion of the Bernina family, they of the sewing machines, who provided him a modest remittance. Joseph said he’d been under psychiatric care, but that he was now allowed to go free. The doctor told him that he wasn’t crazy, but that his mind worked too fast. So far, so good: two days along the Danube and we’d already met a direct descendant of kings.

In the latter stages of WWII, the Hohenzollerns were evicted from their sprawling castle to make room for Marshall Pétain and his staff of 80 running France’s Vichy government, which by this stage of the war Hitler did not trust. The Hohenzollerns were temporarily rehoused in the von Stauffenberg castle near Ulm (a day’s ride away along the Danube), which was now unexpectedly vacant because of Claus von Stauffenberg’s bomb-in-the-bunker plot to kill Hitler and his and his family’s execution and dispersal to concentration camps.

The German countryside is spotless and well-cared for, with fields in neat rectangles and crops in militarily precise rows. The fields are spotlessly clean. We observed one farmer in a tractor pulling a disc plow who, after crossing a narrow, tarmacked lane where a few bits of clayey loam had fallen off the discs, parked across the lane, got out, and, with flat shovel and broom, swept the pavement clean. And more than once we saw rural residents wash their trash bins with hose and soap in spite of having enclosed their rubbish in plastic bags. Such persnickety attention to detail is expressed in casual idioms. Instead of a listener responding to a speaker with the usual nods, OKs, yeahs, and such that confirm he’s engaged, Germans always interject genau, meaning “precisely.”

So far, so good: two days along the Danube and we’d already met a direct descendant of kings.

These traits are inevitably — and unfairly, I might add — coupled with a perception that Germans lack a sense of humor, or that whatever humor they do have is scatological or pratfallish and slapstick, and that they don’t get irony or sarcasm, interpreting the latter literally. I decided to test this. After a delicious and typical German meal consisting of schnitzel with onion gravy accompanied by nuddeln mit Riesling in the town of Munderkingen, the chef came out and asked, “How was your dinner?” He didn’t get many Americans. He noticed that our plates had been wiped clean.

“Awful!” I answered. Everyone around us laughed.

And Germans aren’t as rigid as often perceived. Although autobahns are famous for lacking speed limits, German drivers, in our experience, are tops. Bikes are treated as traffic, respected as such and shown every consideration possible, including legal and de facto forbearance: they are welcome to travel on sidewalks and even against traffic on one-way streets.

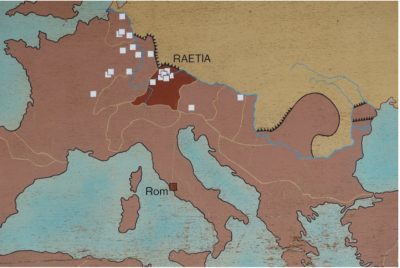

On September 25 we left Baden-Württemberg and entered Bavaria at the big city of Ulm, birthplace of Albert Einstein (and the aforementioned von Stauffenbergs). Our lodging, the Hotel Romer, was built on top of a Roman ruin from AD 380. The central part of its dining room is elevated three feet and sits atop an exposed Roman foundation. The northern limits of the Roman Empire in Eastern Europe roughly followed the Danube. We were impressed at the sophistication and number of preserved Roman ruins along the way.

Once we were in sunny Bavaria, biergartens outnumbered banks, grocers, pharmacies, and gas stations, combined. The varietal selection is not as limited as is sometimes perceived. Though German law, the Reinheitsgebot, permits only water, hops, and barley as ingredients in beer, only lagers are brewed. However, that’s a tad misleading. There are both light and dark lagers. They vary in hop and alcohol content and come in various hues. So much for convention. There is also Weizenbier, or wheat beer, varying as the above. All beer menus also offer a diesel, a beer and cola combo. But the creativity doesn’t stop there. Fruit juices and wine are often consumed with a spritzer of seltzer, while water always comes in three varieties: natural, classic (highly carbonated), and medium, with just a sprinkling of bubbles. There are many brands, each differentiated by highly variable mineral content.

At Blindheim we cycled through the four-mile-long field of the Battle of Blenheim, the turning point in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1715), a war — to cite Andrew Eames, author of Blue River, Black Sea — “whose name has provoked volleys of yawns in schoolrooms across Europe,” and in North America, where it’s known as Queen Anne’s War. The details are too long and complicated to recount. Suffice it to say that this was one of the largest battles in European history. The British were fighting alongside the Prussians, Austrians, Dutch, and Danes in the so-called Grand Alliance against the French and Bavarians over who would succeed the childless and dead Charles II of Spain. The real contest was over the question of whether dynastic succession was more or less important than the European balance of power.

The Franco-Bavarian army consisted of 56,000 men, the Grand Alliance of 52,000 men, led by the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy. The battle was long and hard fought, with control of the village and field whipsawing back and forth. But Marlborough finally cornered the French against the swampy ground at the junction of the Nebel and the Danube, inflicting 30,000 casualties and drowning 3,000 cavalry — horses and all — in the Danube.

Though the battle did not end the conflict, it was decisive — for the present. French hopes for a bigger slice of Europe weren’t destroyed, but only postponed until the Bonaparte juggernaut 100 years later.

Outside Donauworth we caught up with a lone biker from Austin, Texas, pedaling away the heartbreak of a divorce. After the usual biker talk — where are you from, how far are you going, how’s your German, etc. — we got down to more interesting stuff. He said that Hungary had just opened up to vaccinated and tested Americans. I noted that in spite of his middle age and expansive middle he wasn’t riding an ebike. He gave me a look that questioned, what’s wrong with ebikes? “It’s cheating,” I opined.

Although autobahns are famous for lacking speed limits, German drivers are tops. Bikes are treated as traffic, respected as such and shown every consideration possible.

He responded that he’d run into a 70-year-old who was riding an ebike but only turned it on when he was going up hills. He — the Austin biker — was a serious, melancholy sort. I said I was 72. He looked me up and down and responded, “Seventy isn’t what it used to be.”

“Don’t rain on my parade,” I shot back, and got a smile.

Germany still has lively, successful bookstores in nearly all the towns we passed through. How refreshing! Additionally, looking at women elicits a smile, not a rebuff caused by the fear that one might be a pervert or patriarch. Interacting with children is taken as a sign of friendliness, not pedophilia. And, surprisingly, hairstyles are no indication of gender — except for beards.

That night in Donauworth, an attractive, tough-looking blonde checked us in to our lodging. She was not as friendly as other hosts, and did not register us, did not ask for our passports or covid cards, not even the next morning as we left. Now, nearly all our lodgings required photocopying our passports, filling out forms that at times even asked for our mothers’ maiden names, and even included a form for the taxman. So this blonde’s behavior was very out of the ordinary. That evening I overheard her speaking what sounded like a Slavic language with three equally rough-looking fellows. I suspected they might somehow be scamming the owner. However, we checked out using a Visa card and she thanked us kindly. Can’t cheat the owner using a credit card on the inn’s machine; she must have had some very relaxed protocols.

The 66km ride to Ingolstadt was easy but hilly, made tougher by six days of continuous biking. We were slowly losing altitude. Cornfields and alfalfa gave way to sugar beets. So far, no sign of decrepit or dying towns or slums. We rested a day in Ingolstadt, home to Audi and the setting of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, fictionally centered at the medical school of the University of Ingolstadt.

You can always identify a German because he loves paperwork.

On September 26, Germany held federal elections. We’d been seeing placards for the various parties posted on lampposts everywhere. Although German politics are about as entrancing as Canadian politics, these elections were notable because Angela Merkel, center-right Christian Democrat (CDU-CSU) Chancellor of Germany for 16 years, was stepping down. A new government would take over.

The main contenders have always been the CDU-CSU and the center-left SPD (Social Democrats). But because of the similarities of the two main parties, smaller contenders have been gaining ground for some time, with one of the minor parties usually joining a biggie in coalition to get the 50% majority to govern successfully in parliament. From right to left these are the AFD (Alternative for Germany), which advocates leaving the EU and restricting immigration, especially of the Islamic sort; the FDP (Free Democrats), which advocates largely libertarian policies; the Greens; and Die Link (The Left), which advocates leaving NATO and allying with Russia.

The election results were thus: SPD, 26%; CDU-CSU, 24%; Greens, 15%; FDP, 12%; AFD, 10%; Die Link, 5%. This time the two main parties’ vote count was so low that only a three-way coalition — for the very first time — would allow for the formation of a federal government; but at least, due to their similar showings, both main parties had a shot at governing. I got great satisfaction that the AFD beat Die Link decisively. The AFD has been maliciously labeled as neo-Nazi. It took the case to court, averring the characterization was slanderous. In 2021 the court agreed. On the other hand, Die Link proudly wears the label of heir to the East German regime. In fact, its defeat was nearly enough to eradicate them. Die Link only actually got 4.9% of the vote, disqualifying it from a seat in the Bundestag, the German parliament, where a 5% minimum vote tally is requisite.

One month after the election, while riding in Hungary, we ran into a German family. I asked them if a coalition government had yet been agreed upon. The odds-on favorites were the SPD, Greens, and FDP to reach a governing agreement. He said that the parties were still working on the paperwork for a coalition. I responded that in the US we have a joke: you can always identify a German because he loves paperwork. He laughed in recognition.

Speaking of politics . . . We passed an amazing sight outside of Neuburg. A giant statue of Joseph Stalin, easily 20 feet tall, in the yard of a large stone, brick, mortuary monument and statuary outlet. It was a Sunday, so the business was closed. There were no fences, so we stopped and entered to marvel at it. There was no one to ask for its backstory. Was it for sale? Perhaps something on its pedestal would give us a hint about its provenance. A relic from the fall of the Wall? Yet this was Bavaria, always in West Germany, though the old East German border was only about 125 miles away. Or a relic of communist Eastern Europe? Then, close to it, we spotted two life-sized statues of Ernst Thälmann, leader of the German Communist Party during the Weimar Republic, which he tried to overthrow with his paramilitary organization. He was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 and later killed at Buchenwald. For unfathomable political reasons Stalin did not ask for his release after the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact. Ostalgie, nostalgia for the DDR, still runs deep among some . . .

After another rest day we headed for Kelheim. The pungent smell of silage and livestock manure — for us, a not unwelcome aroma — filled the air. Hops fields, with their tall, tilted, and wired wooden supports dominated the countryside. This was beer country, in fact the birthplace of German beer. The shoreline began to rise ominously. At Weltenberg we reached the start of the Danube Gorge, where the river’s width is narrowed to less than 200 feet by sheer limestone cliffs that tower high above the gorge. The gorge lacks an accessible shore, so a ferry plies the 4.5 kilometers between Weltenberg and Kelheim, providing a connection for bikers and daytrippers visiting the Weltenberg Benedictine Abbey, gawking at the fantastic and bizarre cliff formations downstream, and experiencing the many treasures of downstream Kelheim.

The Weltenberg Benedictine Abbey, founded in 610 by Columban (Irish) monks, guards the Gorge’s portals. It is the oldest monastery in Bavaria, and it was here in 1050 that German beer standards were first developed and formalized. We each drank a dunkel as we waited for the next ferry to Kelheim. On the abbey’s outside corner wall a series of marks, similar to the lines and dates that parents scribe on doorway trim to record the growth of a child, measure and date the Danube’s record floods. The highest mark, about three stories up, dates from 1784; while the most recent, in 2013, is 12 feet above grade.

On the boat we had another beer. The waitress was from Macon, Georgia. She’d married a Bavarian and spoke German with a Georgia drawl, an endless source of merriment to her customers and one that drew unusually fat tips.

Hops fields, with their tall, tilted, and wired wooden supports dominated the countryside. This was beer country, in fact the birthplace of German beer.

Atop the green forested mountain overlooking Kelheim and marking the downstream end of the Gorge, an impressive, round, stark white, single-layer wedding cake monument to Teutonic kumbaya stands out in the evening sun. Inside, 34 winged angels stand in a circle, holding hands. It is the Hall of Liberation, built by Bavaria’s King Ludwig I to commemorate the defeat of Napoleon’s invasion at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, which required for its success the union of 34 German states. To visit it we faced a steep, 500-foot ascent at the end of the day. After WWII, German pride disappeared. Even the words to Deutschland Über Alles were changed. Pride was equated with arrogance, which in turn was equated with Nazism. So we found any monument that embodied German pride, be it Walhalla (as you’ll read below), the Hall of Liberation, or, especially, the tiny and infrequent memorials to the WWII dead in small burgs, compelling. But after two beers, we decided to take photos from below.

Kelheim is an old Celtic town dating from about 500 BC. Its reconstructed Celtic gate, made of logs and stone, looking like an old Western frontier fort, stands where the remains were unearthed. An archaeological museum details Kelheim’s origins.

The night before the ride to Regensburg on the last day of September, the mercury dropped to 38°. Thenceforth, mornings would be bracingly cold, but with perfect biking temperatures throughout the day. It was to be a relatively short ride to allow for sightseeing.

Regensburg, an old Roman town, is one of Europe’s best preserved medieval cities . . . as good a reason as any to lay over again. The Porta Praetoria, the city’s Roman gate, was built in 179 AD. It sits next to the river. The East Gate, built in 1284 to edify the Holy Roman Emperor when he deigned to leave Vienna and visit the provinces, also still stands. Regensburg was the capital of Bavaria for over 700 years. In 1146 it became the site of the first bridge built over the Danube. After much reconstruction and restoration, the bridge now carries motor traffic. As the only one over the Danube connecting Central Europe with Italy, it made Regensburg a focal conduit for trade and enriched the city. The effects are still visible in the old merchants’ houses with their characteristic stone towers.

Regensburg was the home of Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), discoverer of the laws of planetary motion. The house where he lived for a while and died is now the Kepler Museum. It’s on a main street — Keplerstrasse, in fact — one street removed from the river and easy to find . . . but not by us. We must have crossed in front of it half a dozen times. It turned out to be very modest, shared walls with adjacent structures, was temporarily fenced (for renovation), and had scaffolding in front that blocked its small sign and street number.

More recently, Regensburg was the home of Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI, the only modern pope to abdicate. He taught theology at the University of Regensburg from 1969 to 1977. We did not seek out his residence.

German cities have an odd sort of locational capitalism, reminiscent of business clustering in Lima, Peru, where, for example, eyeglass vendors are all on one street, adjacent to each other. Attempt to enter one, and the next-door merchant will entice you away with some marketing mendacity. It makes for some extreme, cutthroat competition that, as a customer, I found unpleasant. Many German cities cluster grocery stores right next to each other, or even in the same shopping center — Rewe, Edeka, Aldi, Lidl all sharing a common parking lot. Shoppers can sometimes take advantage of this situation. For bulk discount items, into the Lidl or Aldi, then back to the car, followed by a visit to the Rewe for deli items or the Edeka for greater brand choice. In the US, grocery stores space themselves widely to capture nearby residents through convenient location. The German custom made little sense to us. However, one US retailer follows a similar strategy. Lowe’s, the home improvement mega store, makes a policy of locating outlets close to Home Depots — a tactic reminiscent of Lima’s small businesses.

On the trail to Straubing we rode by Walhalla and stopped by for a chat with Wotan. He blessed our journey and wished us gute Fahrt. Walhalla is an imposing classical temple sitting atop a mountain with 348 marble steps leading up to its portico. It’s another construction by Ludwig I, built in 1842 as a pantheon of German heroes. One hundred thirty marble busts and 65 plaques of worthies having some Teutonic connection, including Dutch, Flemish, Swedish, Russian, English (among them three kings), and at least one American, are arrayed along the interior perimeter of the main hall. Nineteen busts have been added since 1945. Max Planck was scheduled for 2019 but had not yet appeared.

By now we’d observed that both barge and pleasure craft traffic on the river had noticeably increased. A half-dozen tributaries had joined the Danube, substantially increasing its volume. The stream becomes fully navigable for river ships and barges below Kelheim, although many smaller craft can navigate as far upstream as Ulm, 120 miles away.

In Straubing, a beautiful baroque town, we stayed in a hotel right on the main square. One pleasant atmospheric feature (albeit not so pleasant if you have trouble sleeping) is the hourly — sometimes half-hourly, or even quarter-hourly — sound of the village church bells. Some towns leave the task to one church, so as to avoid competing clangings. Straubing doesn’t.

Some lodgings along the route had fahrad garages specifically for bicycles. The next morning, pushing our bikes from the fahrad garage to the hotel’s main door, we passed all the lodgers’ parked cars. I stopped cold when I noticed a tiny, almost inconspicuous bumper sticker on one of them. It was the very first bumper sticker we’d seen in Germany. My sister-in-law, a former East German, later said that Germans are very fussy about the looks of their cars and take great pride in having them dent-free, ship-shape, and clean. True enough, according to our observations. But here was a bumper sticker, and it said, “Fuck Greta,” the words bracketed by two extended middle fingers. Of course it was a reference to Greta Thunberg, the Swedish climate change activist and Time person of the year. It was a refreshing sign of individuality in a country perceived to be full of conformists. More interesting was the sentiment it revealed in a country that voted to eliminate all nuclear power plants and to phase out coal and gas plants, a country seemingly determined to rely exclusively on wind and solar power — the latter in a place more akin to Portland than to Phoenix. The new Social Democrat-Green coalition is dedicated to fulfilling these aims.

The car next to that one had a Hungarian license plate. But it was the heavy-duty ebike rack on its bumper that caught Tina’s eye, a rack that didn’t seem to require lifting the heavy ebikes to put them on. While we examined it, the car’s owner came out of the hotel and engaged us. He spoke good English. He answered Tina’s questions and proudly said that his ebikes had a range of 80 miles. I retorted that our bikes had unlimited range. After a good laugh he said it was refreshing to banter with us; in his opinion, Germans lacked a sense of humor, and he avoided talking with them. After saying that his son was attending Arizona State University studying “who knows what” (more laughter), he said that Hungary follows no covid protocols . . . once one gets in.

But here was a bumper sticker, and it said, “Fuck Greta,” the words bracketed by two extended middle fingers.

Outside Deggendorf we observed another curious German custom that we’d seen before, but here along the Danube, it was both extensive and lovingly exhibited. German homes are adorned with flower gardens or, lacking space, elaborate pottings. But we never saw vegetable gardens alongside homes. These are located outside towns in dedicated, community areas — in neat, individually fenced plots, one next to another — with cute tool and hanging-out sheds, sometimes graced with a tiny veranda. Plot holders might spend an entire weekend puttering in their garden.

On the way to Passau, we reached the first of many giant dams with navigation locks that control flood waters and facilitate commercial navigation on the Danube’s German portion. Tomorrow, a day off to plan our sojourn into Austria, the Eastern Kingdom (Österreich). We visited St. Stephen’s cathedral, which housed — reputedly — the world’s largest organ, and then — the dachshund museum! How can you be disappointed with something like that? But we were, mildly. The place was filled with dachshunds — dachshunds in wood, dachshunds in ceramic, stuffed dachshunds, photos of celebrities who had owned or were otherwise associated with dachshunds, and many dachshund mementos for sale. The only thing lacking was any history of the dachshund, the origin of the breed or why it was developed. The people who ran the place just wanted to share their love for the little wiener dogs.

What can I say after that? For a change, we sought out a Thai-Vietnamese restaurant for dinner. At its entrance lay a stack of covid tracking forms required for all eateries so that in case of contagion, contacts can be traced. Everyone ignored them. In this restaurant, no one wore masks or asked for vaccination papers. Our perception of Asians being mask freaks was an unfair typecast. Not knowing either Thai or Vietnamese, I greeted the staff with a Mandarin ni hao. Frowns all around. A faux pas, I take it. They told the cook. He came out and gruffly asked where we were from. “Arizona.” I replied.

He smiled and gave us a thumbs up, followed by a corresponding frown and thumbs down for China. And then he volunteered two thumbs up and strongly pronounced, “Trump!” a word he repeated with a big smile as we left after dinner.