Some people leaf through books of history, trying to see whether they are interested in the subject or the style. Others flip immediately to the thin gray line that separates the reams of white: the photo section.

The photographs, of course, may have been included as mere visualizations of the text. An article on Iwo Jima would not be complete without the black and white photo of the flag-raising on Suribachi; an essay on the Titanic may include sepia-toned pictures of her builder and captain; a history of the American space program can be complemented by a color photo of an astronaut snapping a salute in front of a wrinkled flag, planted in a desolate lunar landscape.

The same photographs may be viewed in a different way: they may be analyzed for their artistry, their composition, their dynamics, their suggestions and symbolism. Whole fields of art history have been developed in the pursuit of such knowledge. What is the significance of the dominant lines in this picture of people disembarking at Ellis Island? What does the high contrast in this war photo symbolize? What imperialistic motifs can be discerned in this photograph of colonial subjects?

As a student of history who is also an avid amateur photographer, I look at the photographs first, but I am not necessarily looking for either their visualization or their artistry. I wonder, instead, about their creation. Who took these photos? What was he or she like? Why was he there at that moment? Why did she take the photograph? What kind of equipment and technique did the photographer decide to employ? Did he or she take other photographs, and were they widely seen? Today, it is easy to forget the effect that individual photographers have had on the ways in which we view not only photographs, but also the world they represent. Similarly, with photographic technology so rapidly advancing, it is much too easy to neglect both the individual toil and the individual technique that went into the creation of past iconic images.

Photography has always been an individual art and science. At the most fundamental level, one always makes two basic choices in manipulating the camera – when to trip the shutter, and what to include or exclude. Yes, there are confining factors: the limitations of space and time, the pressure to produce something that will be accepted or required by a certain audience. There are also the conflicts, moral or practical,

With photographic technology so rapidly advancing, it is much too easy to neglect both the individual toil and the individual technique that went into the creation of past iconic images.

that may take place in the photographer’s mind. There is even the effortlessness, the apparent lack of any necessity for deci- sion, that is the blessing of cliche pictures. But the camera has one operator; he or she alone is the mind behind the machine. As has long been whispered in the world of true photographic artists – and related to me many times through wise photo- graphic mentors – “no camera is as good as the photographer behind it.”

Icons and Ironies

The day is cold and damp; salt spray stings the unshaven faces of helmeted men, huddled together in heaving, pitching landing craft as they speed toward the foggy shore ahead. Up on the cliffs, frantic shouts and piercing klaxons send sleep~ red-eyed companies into concrete shore defenses to repel an invasion they had no idea was coming. Soon, whining bullets and screaming mortar shells sweep the beaches; men run, shout, scream, and fall. Amid the blood and chaos of the first assault wave, a young Hungarian national wearing the com- bat uniform of a U.S. soldier crouches, pauses, leaps, and runs with the other men. But he is no ordinary soldier, and what he shoots with does not kill.

Swinging from leather straps around his neck are two Zeiss- Ikon Contax 35mm cameras and a Rolleiflex 2 1/4″ by 2 1/4″ camera, wet and muddy from the rough landing on Omaha Beach. The young man’s combat pouches are filled with neither ammunition nor medical dressings, but preloaded rolls of black and white 35-millimeter film. He is Robert Capa, a photojournalist for Life magazine. In the first two hours of the D-Day invasion he shot a total of 108 photographs of U.S. soldiers under fire, switching from one grimy camera to the other, reloading as quickly as he could.

As the Americans cleared the beachhead and prepared for their first push into occupied France, Capa’s negatives were rushed back to Life’s photographic labs in England by one of the first returning ships; they arrived at nine that evening. Then, in a dimly lit darkroom, one of photography’s greatest tragedies occurred. Eighteen-year-old Larry Burrows – him- self later to become an iconic photojournalist of the Vietnam War – was there when an exhausted messenger arrived in the office, his uniform soaked with sweat, carrying the carefully packaged, precious film. In a book by John Morris, Burrows tells the story:

A scrawled note said that the action was all in the 35-millimeter, that things had been very rough, that [Capa] had come back to England unintentionally with wounded being evacuated, and that he was on his way back to Normandy … Photographer Hans Wild … called up … to say that the 35-millimeter, though grain~looked “fabulous!” I replied, “We need contacts – rush, rush, rush!” … A few minutes later [the lab technician] came bounding up the stairs and into my office, sobbing. “They’re ruined! Ruined! Capa’s films are all ruined!” Incredulous, I rushed down to the darkroom with him, where he explained that he had hung the films, as usual, in the wooden locker that served as a drying cabinet, heated by a coil on the floor. Because of my order to rush, he had closed the doors. Without ventilation the emulsion had melted.

Only eight frames of 35mm film were saved from the oozing mess of celluloid that lay dripping from the film hangers. These were published in Life with a dryly disdainful caption that labeled them”slightly out of focus.” Capa was himself to meet a tragic, anticlimactic end: one month short of a decade, after that decisive June day, he lay dead at the side of a dirt’ road halfway across the world, his leg blown off by an anti- tank landmine. He had worked his way forward of a French patrol under fire from Vietminh guerrillas, running and lift- ing his camera (one of the three that had accompanied him on Omaha Beach) to photograph the advancing soldiers, when he stumbled into a minefield.

John Steinbeck wrote in tribute after Capa’s death: “No one can take the place of any fine artist, but we are fortunate to have in his pictures the quality of the man … he made a world and it was Capa’s world.” This “world,” in the 50 years since it became a part of history, has made its mark on ours. We have seen Capa’s eight blurry frames, in one form or another. They have been printed in books and magazines; they have been used as production material for a myriad of war films; they have become iconic images of monumental events. Having been repeatedly exposed to these photographs, whether in their original form or in media that borrow from them, we have relegated Robert Capa to a name located chiefly in books of photographic history buried in library archives – his courageous efforts and brilliant talent faded by the passage of

As has been related to me many times through wise photographic mentors, “no camera is as good as the photographer behind it. “

time. His unique personal accomplishment resulted in his eclipse as a personality – yet his accomplishment was no less real, no less individual.

I, as a young photographer, was soon to realize his individualism in a discovery of my own; a chance historical find was to propel me backward in time and place me – in a startlingly realistic way – into Robert Capa’s shoes.

Lessons From History

One winter day found me in a dim living room that reeked of old metal and the strangely aromatic smell of machine oil. I had come to visit the home and workshop of Jack Biederman, a retired high school photography teacher and camera repair- man, to have one of my older 35mm cameras tuned up. My fascination with old photographic equipment turned to elation as I looked around his living room, packed from floor to ceiling with boxes of cameras and lenses, accumulated by Mr. Biederman in his long years of teaching, repairing, and collecting. That’s the kind of person he was. As Mr. Biederman pointed out treasured cameras with his shaking, bony finger and described them in his raspy voice, my eyes came to rest on a worn leather camera case embossed with the words “ZEISS-IKON” in angular Germanic characters, lying atop a pile of half-disassembled cameras.

I had seen a case like this before, hanging from the neck of a photojournalist pictured in a World War II book. A cloud of dust rose from the pile as I lifted the case; it was very heavy. As I opened it, bright chrome finish and black lettering met my eye; the elegant words “Contax” and “Carl Zeiss Jena” set my pulse racing. A friendly chat and $80 later, I found myself in possession of a 1938 Contax II 35mm camera with a 50mm f/2 Zeiss Sonnar lens, the same model of camera and lens that Robert Capa had shot with throughout his career – a camera responsible not only for the Omaha Beach landing photographs but also for pictures of peasant refugees fleeing the Japanese advance in China, the haunting “Death of a Loyalist Soldier” in the Spanish Civil War, and the last images of French soldiers advancing in Indochina, just before Capa’s death.

The shutter of the Contax wasn’t working. Zeiss cameras have always been known for their complex internal mechanics, designed by German engineers for reliability, not ease of repair. Even the highly skilled Mr. Biederman had shied away from putting the septuagenarian camera back into action. However, some research on the internet turned up an expert Zeiss repairman who was in business not far from my home. Within six months he had sent the camera back to me, cleaned, oiled, and as ready for action as the day it left the factory nearly 70 years before.

I spent that afternoon familiarizing myself with the workings of the Contax II, and in doing so, quickly gained a new appreciation for the amount of technical skill Capa needed to operate his camera. The back of the Contax, unlike that of modern 35mm cameras, did not swing open but detached completely to expose the shutter and the film take-up spool. The spool itself wasn’t attached to the camera, but promptly fell out as the back was opened. Film had to be threaded into the spool; then both film and spool had to be loaded carefully into the camera. Seating the film so as to engage the film trans- port sprocket wheels was a pain. By the time I shut the back and successfully wound the film, my fingers were sweaty and sore. As I labored, I had a vision of Capa trying to load his Contax in the same way – not in a comfortable suburban bedroom as I was, but on a blood-soaked battlefield with bullets and shells kicking sand up around him. It was unbelievable. The man must have had nerves of steel. Certainly, “no camera is as good as the photographer behind it.”

And now I would add: Every good cam- era offers a chance for its users to define them- selves. It asks the photographer: What really interests you? What is your vision? How good are you at realizing it? A camera is really but a tool, an easily accessible outlet for individualism that is both easy

to use and hard to master. However, sometimes all it takes is an open mind and the ability to see beyond the camera as a mere tool, instead sharing one’s own thoughts and being with the world through the secondary, mechanical processes of photography.

If you’re looking for examples of the importance of individuality, look no farther than the photo of Albert Einstein that can be found on T-shirts and physics posters everywhere, the photo that shows the famous scientist sticking his very large tongue out at the camera. It’s a bizarre but, presumably, endearing view of the man best known for his brilliant physics and frazzled gray hair. But while it is, indeed, a view of Einstein, it owes more to the individualism and quick reflexes of the photographer than to any real zaniness in its subject.

Einstein was famous enough that people stopped him on the street and asked, “Aren’t you Professor Einstein?” and even, “Can you please explain ‘that theory’?” Tired of the public eye, Einstein sought clever ways to turn inquirers away; in a famous counter to the questions above, he would bow humbly and say in a thick German accent, “Pardon me,

In the first two hours of the D-Day invasion, Robert Capa shot 108 photographs of U.S. soldiers under fire. All but eight of the photo- graphs were lost.

sorry! Always I am mistaken for Professor Einstein!” Then, on March 14,1951, his 72nd birthday, his adverse reaction to pub- lic curiosity was recorded on film.

The exhausted scientist was returning from an event held in his honor on the campus of Princeton University when he was accosted in his car by a swarm of press photographers. His picture had already been taken many times that day, and he was tired of smiling and being blinded by insistent flashbulbs. He shouted, “That’s enough! That’s enough!” but was immediately drowned out by the photographers’ demands for “one more photo, Mr. Einstein!”

Staff photographer Arthur Sasse from United Press was on hand that day, one of the throng that surrounded Einstein’s car. Sasse pushed his way to the front of the crowd and bellowed, “Look this way, Mr. Einstein!” At that moment, Einstein, fed up with the unrelenting press photographers, turned to face his loudest accuser – none other than Arthur Sasse – and furiously stuck out his tongue at him. Instead of waiting for the physicist to revert to a more normal expression, Sasse saw a distinctive photograph and fired off a single frame with his press camera. It was his only chance, as Einstein’s driver revved the car’s engine in impatient protest immediately afterward, and the photographers quickly scattered.

Einstein was later presented with a superb print of Sasse’s technically well-executed photo and immediately took a liking to it – as would millions of physics students in the decades to come. Today “Einstein’s Tongue”can been seen in odd places all over the globe, from coffee mugs to body tattoos. It owes its popularity to the quick thinking of a now-forgotten UP photographer, who performed a radical renovation of his subject’s personality, as perceived by the crowd – and perhaps even by the subject himself.

Immediacy and Individuality

Photographer Dorothea Lange wrote in her later years, “The camera is an instrument that teaches one how to see without a camera.” Her statement was cruelly clarified by one of the most haunting pictures of the 20th century.

Two decades after Robert Capa waded to shore with American troops under fire at Normand)’, the United States was involved in another conflict – not in Europe and not against fascism, but against the spread of communism in Vietnam. As the war dragged on, the casualty list lengthened, and American public opinion grew polarized over the issue of whether to withdraw from the conflict, another young man took his place among the great iconic documentary photographers. He was 35-year-old Eddie Adams of the Associated Press. At the first noonday of February, 1968, his single decisive photograph, taken on a deserted Saigon street with a Nikon 35mm camera, burned the brutality of the Vietnam conflict into the minds of the American people.

At a few moments before noon, when the Tet Offensive had been underway for less than 24 hours, Adams watched as two South Vietnamese soldiers pulled a prisoner out of a door- way at the end of a Saigon street and escorted him down the sidewalk. The man looked to Adams like a Vietcong soldier, though he was clad in the plaid shirt of a civilian. What happened next occurred in a heartbeat, as Adams remembered:

When they were close – maybe five feet away – the soldiers stopped and backed away. I saw a man walk into my camera viewfinder from the left. He took a pistol out of his holster and raised it. I had no idea he would shoot. It was common to hold a pistol to the head of prisoners during questioning. So I prepared to make that picture – the threat, the interrogation. But it didn’t happen. The man just pulled a pistol out of his holster, raised it to the VC’s head and shot him in the temple. I made a picture at the same time.*

The photograph, later titled “Saigon Execution,” was care- fully processed and was broadcast around the world on the following day by the AP radiophoto network. Public reaction was swift and fiery. Antiwar protesters around the world took it and ran with it. Never mind that the executed prisoner turned out to be a notorious Vietcong officer who had been leading killing squads only the day before, or that the executioner was a highly capable and well-respected South Vietnamese general – this photo “proved” all too well the cold brutality and meaningless sacrifice of war. It still ranks as one of the three iconic images of the Vietnam conflict – along with the heartrending picture of wounded, naked Vietnamese children fleeing a napalm strike, and the photograph of helicopters airlifting the last of the American forces from the roof of the Saigon consulate.

What you make of a picture shows who you are, not just what the photograph depicts. Yet photographs do have an effect, as Lange suggested, in teaching people how to see. Admittedly, this may take a long time to happen. When Matthew Brady’s photos of the carnage at Antietam were displayed in Washington, during the Civil War, audiences exclaimed, “How ghastly!”, but did nothing: photography was too new a technology; the viewers weren’t accustomed to the reality that the pictures purported to represent. When Capa’s photos of men struggling and dying in the waters of Normandy appeared in Life, the American public – perhaps also not used to the raw quality of the images – took it as another just sacrifice and carried on. But when Adams’ photo of the Saigon execution appeared in American and world media, sped by technology that was on the cutting edge of communications, it galvanized many people’s thoughts overnight. The sense of immediacy – the sense, at least, of a sud- den intrusion of unmediated, unjustified brutality – was greater than before. Eyes that had become accustomed to the contemplation of war, and had even accepted its photographic images as classical representations of reality now looked at an image that was disturbingly hard to fit in the comfortable, classical frame.

By the time that Adams’ photo was circulating around the world, the camera was no longer an uninformed, removed observer (if it ever had been), but a participant in changing the world. Photography was now not only an “extension of the eye” (a concept coined by early documentary photographers) but an extension of the individual voice and spirit – the voice and spirit of the viewer as well as the photographer.

This fulfillment of Lange’s prophetic statement was not to come without an artistic price – if you take the concept of “seeing without a camera” as including the concept of “seeing without any necessity of art or technique.”

Photography was from its infancy a marriage of technology and art. Early photographers were more alchemists than artists, spending immense amounts of time working in unventilated darkrooms, mixing chemicals, preparing solutions, and, more often than not, exposing themselves to toxic substances. Until the first decade of the 20th century, the standard camera itself was heavy, cumbersome, and incapable of freezing motion; it was only in the mid-1920s that widespread photographic technology – high-speed lenses, smaller cam- eras, faster shutters, more sensitive film – started to enable the professional photographer to go to the action and capture it, rather than needing the action to come to him. The aggressiveness of technology shaped public perception of photographers as seekers and purveyors of truth.

Yet as photographic media became a vital component of the international information age, the sun was quickly setting on the days of the individual technician-photographer. The

“Saigon Execution” is one of the three iconic images of the Vietnam conflict – along with Vietnamese children fleeing a napalm strike and helicopters airlifting the last American forces from the roof of the Saigon consulate.

expansion of mass-market technology and consumerism into the field of photography was a blow to the individualism of technique.

A few weeks ago, I was walking through my oId high school campus in Northern California. It was a beautiful sum- mer day; the sun was setting over the golden hills. There was only one flaw in the vista: a pile of junk that the janitors had dumped outside, awaiting the garbage disposal service. As I approached this large pile, I saw something at the bottom, a strange device … Coming closer, I realized that it was an old photographic enlarger, dumped on its side and half covered with dirt and pine needles. My heart broke. I had used this particular enlarger to print countless black and white pho-

“The man just pulled a pistol out of his holster, raised it to the VC’s head and shot him in the temple. I made a picture at the same time. “

tographs in my high school days, often staying after school for hours on end, watching images appear like magic in the developing chemical. Now the equipment that had served me – and hundreds, if not thousands of former students – so faithfully was only a rusting, rotting frame, dumped by the wayside to make room for the all-digital laboratory that the school was constructing.

Photographic technology has developed so far that little or no technical skill is required to produce decent photographs. For good photographs, composition is still necessary, and so are timing and all the other classical artistic elements; but the days of darkroom mastery, careful equipment selection, and the intimate feel for changing conditions of light are fading into memory, replaced by automation and computerization. Anyone can pick up an inexpensive digital point-and-shoot, aim and fire it, and produce a halfway decent image – one instantly viewable on a computer screen. Hours of darkroom work and skillful manipulation of film, paper, and chemicals have been reduced to computerized procedures that are faster than the click of a mouse. Yet in the process many decades of individual skill and artistry have been abruptly relegated to the realm of nostalgia.

Up to Par?

“God and Man” would have been both excited and disap- pointed by the events I’ve described.

Leopold Godowsky Jr., and Leopold Mannes, inventors of the once-ubiquitous Kodachrome, are two of the greatest exemplars of individualism in photography. Extremely talented young musicians, Godowsky and Mannes – such close friends that others jokingly called them “God and Man” – were avid amateur photographers, often spending their spare time in high school on picture taking expeditions. One afternoon in 1917, the pair met to see a motion picture advertised by a local theater as “in full color.” Their hopeful curiosity was dashed when the “color” movie turned out to be murky and dim, with none of the crispness or intensity the boys expected. Almost immediately Godowsky and Mannes set out to develop a color photographic process that would be more efficient, more vibrant, and more accessible than any yet seen.

Though separated – Godowsky went to study and per- form violin at UCLA, while Mannes enrolled at Harvard, pursuing degrees in music and physics – they went on with their research, sharing ideas by mail and testing them during short visits between school terms. By the early 1920s, “God and Man” were together again, having set aside lucrative positions in the world of professional music to toil over chemicals and

This growing age of digital photography has defined two types of new-age pseudo-photographers: the obsessive technocrats and the zealous snapshooters.

films in their family bathrooms and kitchens. Unfortunately their parents – professional musicians who balked at their children’s departure from their “destined” careers – soon kicked them out of their makeshift labs. But the two continued their efforts, eventually catching the attention of Kodak Company researchers, who had been working on a similar kind of color film. One commercial partnership and less than a decade later, the world’s first self-contained color roll-film hit the market, thanks largely to the genius and dogged perseverance of the two young musicians.

If Leopold Godowsky Jr., and Leopold Mannes were alive today, they would be thrilled by the new developments in photography; after all, their invention of Kodachrome took color photography out of the realm of scientists and adventurous professionals and into the mass market. However, they would surely regret the lack of innovation and artistry fostered by the new technology. And they would be horrified to discover that their invention, Kodachrome, has fallen victim to technological progress. Their revolutionary 35mm color slides, once the cornerstone of family photography, now rot by the millions in attics and basements, or are sold as curios and”collectibles” on the internet, or – worst of all – are used as raw material for homemade”artistic” lampshades.

This growing age of digital photography has defined two types of new-age pseudo-photographers: the obsessive technocrats and the zealous snapshooters. The former, with a glut of photographic devices at their disposal, get lost in the technical aspects of photography; these naifs believe that buying the hottest new camera, loaded with all the bells and whistles available, will make them the “best” photographers. The latter type – the snapshooters – mayor may not know any- thing at all about photography; with an automated camera and large memory cards, they simply shoot thousands upon thousands of snapshots, in the thin hope that a handful may turn out well. Talking to some of these photographers is akin to observing a starving man lost in a sumptuous meal; he can hardly stop chewing to savor the taste.

I recently attended a summer carnival held at my church. Children were playing on the grassy back lot, and the pleas- ant chatter of parents and old people mingled with the aroma of home-cooked food. I walked to and fro, sampling some food here, chatting a little over there, and snapping sporadically with myoid 35mm camera as I observed beautiful photographs forming in front of my lens. Taking photographs of the action was a young businessman, not much older than I am. He certainly looked professional. Burdened by two of the most expensive digital SLRs on the market and a formidable arsenal of lenses in his kit bag, he lumbered back and forth, shooting anything and everything. A communal prayer was interrupted by the clattering sound of his cameras firing – neither the pastor’s soft words nor the folded hands could stop this man.

During a lull in his frenzy I asked to see some of his photographs. He proudly passed his largest camera over to me, a monologue about the sharpness and expense of the optics already flowing from his lips. But as I flipped through the digital photographs, I could hardly find a good shot. Although the camera had done a brilliant job of exposing the scenes correctly and reproducing them with unbelievable sharpness, the compositions were terrible, full of jarring artistic mistakes. An informed, creative child of ten could have done better. I handed the large camera back to him and said something about his composition’s need for improvement. This sent him into a thinly-veiled rage; he asserted once more that his cam- eras and lenses were top of the line, and that they had been advertised as capable of making the finest photographs possible. He ended by saying, rather indignantly, that only professionals used such equipment as his, and that I – with my 20-year-old, “obsolete” film cameras – knew nothing of professional photography. My equipment”clearly wasn’t up to par.” I forced a smile and bade him good day; as I turned to leave, he was already firing away at an empty soda bottle on the ground. Here was another example of dogged perseverance; here also, I suppose, was another example of an individual learning how to see by operating his camera. But the results were purely mechanical reproductions of the outside world, cold and thoughtless.

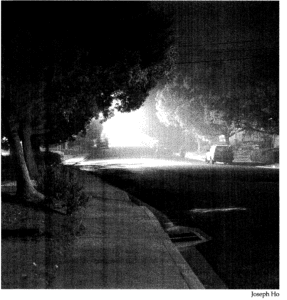

I remember, in comparison, one of the first artistic compositions I had produced with a camera. It was an icy December night, nearly four years previous. A subdued whisper of wonder crossed my lips as I looked up from the tall, metal- cased finder of the tripod-mounted camera. The frigid valley air was thick with vapor; my breath rose lazily from my mouth, smearing the dark backdrop with its ghostly fingers. The image on the focusing screen was barely visible; my

What you make of a picture shows who you are, not just what the photograph depicts.

numbed hands trembled, fumbling with the icy metal focus- ing knob. The streetlight midway down the road was the brightest; I focused on it, bringing its image to a sharp pinpoint. As I watched and waited, the fog lifted slowly, gently.

Like a dark river, the newly paved road rushed diagonally through the frame, uniting the elements. Now was the time. Moving quickly, deliberately, my thumb found the rounded plunger on the shutter release. With a soft mechanical sigh, the thin metal blades swung open, and locked in place. Light streamed through the lens, onto the silver-coated surface of the film. Fourteen seconds. I glanced at the glowing second hand sweeping across the black face of my watch. The time was nearly up. My thumb released the plunger; the shutter blades clicked shut. I had my picture.

“ll n’y a rien dans ce monde qui n’ait un moment decisif” –

“There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment” – words uttered by Cardinal de Retz in the 17th century, later adopted by the pioneering candid photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson as his personal approach to photography. Though the concept of the “decisive moment” has now been relegated to the vocabulary of photographic historians, its meaning is more than merely historical. The decisive moment in photography is not simply the act of the shutter, chopping off a slice of light at the “right time”; it is more than the simple act of creating a “good” photograph. De Retz was right; our world is full of decisive moments – individual moments of discovery, of innovation, of tragedy, of creation, of moments when one is invited to decide whether one’s”equipment is up to par,” in many senses of those words.

From the battlefield photography of Capa and Adams, to the technological genius of Godowsky and Mannes, to the photographic artists who can still shape and further the field, these are the elements that make up true photography – decisive moments created and molded by individuals. No matter how much technology or social pressures may seem to dictate, there will always be ample room for individuality in this art; it is still only one moment, one mindset, one action by one person that is necessary to create a photograph. And one photograph, simple as it may seem, may be all that is necessary to change our perception of the world.