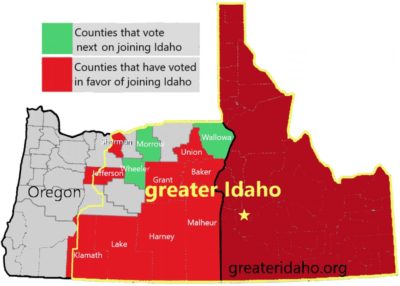

I see on Fox News that two counties in Eastern Oregon will be voting soon on proposals to leave Oregon and join Idaho. I live in Seattle, which is a world away from Eastern Oregon, and not much interested in its concerns. Still, the “Greater Idaho” movement got the attention of the Washington Post in February 2020, and the Washington Post and the New York Times in May 2021, when five Oregon counties — Grant, Baker, Lake, Sherman and Malheur — voted in favor of joining Idaho. Four more counties, Klamath, Jefferson, Union and Harney, later joined them. Now come Wheeler and Morrow counties, which may well vote yes and put the story in the news again.

What to make of it? These are advisory votes only. The Morrow County measure, for example, would direct its commissioners to ask the state to move the border with Idaho, and to meet three times a year to discuss how to promote the county “in any negotiations.” Under Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution, moving state borders requires the consent of the two state legislatures and the U.S. Congress. None of that is going to happen. Still, there is political momentum.

Probably the leaders of Greater Idaho think they have a chance to move the state line, and of course they don’t. But they are sending a message to the Portland progressives.

I know Eastern Oregon only a little. I drive through it every several years. I spent Y2K night, December 31, 1999, as part of a family road trip at a motel in Burns, the seat of Harney County in Oregon’s high desert. Last time I drove through Burns was in early February 2016, when Ammon Bundy and a band of armed “sagebrush rebels” had taken over the nearby Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. There was a standoff; Bundy was eventually acquitted of a crime, though some of the others went to jail for a while. I didn’t see the standoff; I just stopped in Burns for gas. The one thing that caught my eye was a sign on the pump saying, “No ethanol. 100% petroleum distillate.” It felt like a political statement.

Politically, Oregon is similar to Washington. Both are Democrat-majority states that favor land-use planning, abortion, marijuana, assisted suicide, and a dose of wokeness on the west side of the Cascade Range, where the bulk of the population is, and more conservative things on the east side. In 2020, Washington voted 58% for Biden; Oregon, 56% for Biden. (Idaho voted 63.8% for Trump.) In Oregon and Washington, all the counties east of the mountains, facing Idaho, were for Trump with one exception each: in Oregon, the county that includes Bend, a trendy resort town; and in Washington, the county that includes Washington State University. (Idaho has its trendy resort town, Sun Valley, which voted for Biden.) The political contrast across the Cascades is even greater in Oregon than in Washington: in Oregon’s Lake County, on its border with Nevada, voters gave Trump 79.9% of their votes.

Lake is one of the counties that voted to join Idaho. Its problem is too few people. I recall Lakeview, the county seat, for its sad downtown with brick buildings from 1910. Lake County has only 7,896 people — so few that it takes the signatures of only 214 of them to get a measure on the ballot. Judging from the news stories about the “Greater Idaho” movement, the people in Lake and similar counties believe that in Salem, Oregon’s capital, their votes don’t matter. The arithmetic suggests they are right. I think, however, they’re not entirely right.

Consider the appeal Greater Idaho makes on its webpage to the west-side progressives to allow the eastern counties to go. Removing them from Oregon, it says, would “end the gridlock in the Legislature. Without these counties, Republicans in the Oregon Legislature would no longer have the numbers to deny quorum by walking out or slow the legislature by forcing bills to be read in full. Democrats would keep the supermajority . . . Oregon would make progress, becoming more liberal than Washington state, though not as liberal as New York or California.”

Accept that argument. If the Trump counties leave Oregon, the political balance in what remains of Oregon shifts leftward. I can only guess what that would mean for Oregon, but I have a pretty good idea what would happen in my own state. Washington has no state income tax. It has never had one. The people have voted against it at least four times, though the progressives have wanted one for a century. If Eastern Washington went away, we’d have an income tax within five years. Washington state voters have twice voted against racial preferences (affirmative action), the last time by a narrow margin. If Eastern Washington went away, we’d have racial preferences. The Eastern Washington conservatives may feel they get little of what they really want, and they’re probably right, but sometimes they are able to block the left from getting what it wants.

The tension is similar in other states: Upstate New York versus New York City. Upstate Michigan versus Detroit. Rural Colorado versus Denver and Boulder. Rural Nevada versus Las Vegas. Inland California versus Los Angeles and San Francisco. Conflict is built into the geography. And opposition limits power.

If Eastern Washington went away, we’d have an income tax within five years.

I am reminded, too, of Washington’s king of ballot measures, Tim Eyman, who has been putting anti-tax initiatives on the state ballot for more than 20 years. When I was a newspaperman, Eyman said to me, several times, “All initiatives are lobbying.” To Eyman, tax laws were always in flux. Keep pushing the taxers, because they’ll keep pushing you. Never let up! And it’s not only taxes. In Washington, the legislature can amend or repeal a voter-passed initiative after two years, and they can change an ordinary law any time they’re in session. But politicians can be intimidated by a public vote. Fifty-five percent humbles them, and anything over 65% stuns them into submission. In Oregon, the Greater Idaho activists are stirring up their people with these secession measures, keeping them excited. Probably the leaders of Greater Idaho think they have a chance to move the state line, and of course they don’t. But they are sending a message to the Portland progressives: “Stop dumping your crap on us. We don’t want it, and we don’t want you telling us what to do. And these votes show that we have the support of the people here, and you don’t.”

Elections are a way for people to be heard. That’s useful. Some good will come of it — more good, I think, than taking over a federal wildlife reserve.