My French sister, who was green before green was cool, sent me the reference of a book I “had to read.” She is an assiduous reader and a main source of books in French for me. She must have good taste, since her taste frequently agrees with mine. The reference was to a book by a French philosopher, a defrocked monk.

(Why does France have so many of those, I wonder? Irresistible temptations at every cafe terrace?) The book’s topic is “how to survive the spiritual crisis of globalization.”

This kind of advice brings up a slow-burning, barely suppressed exasperation in this ex-university professor. It’s of the impotent kind. I keep asking myself: why do we do such a bad job; why did I do such a bad job explaining what should be obvious? Why isn’t the accumulated wisdom of the economic disciplines sufficient to counter the lies, the inventions, and the childish nightmares of the Left with respect to so-called “globalization”?

Mulling over my sister’s invitation impelled me to try again. This time, I will limit myself to the narrowly possible instead of trying for exhaustiveness. Also, I will stick close to what I know well from personal experience.

To begin with, I must say that often I don’t know what people who are fearful of globalization mean by the word. Mostly, I suspect, it’s because they don’t know what they mean. But I have a pretty good idea of what’s on my sister’s mind, because I know her well and because I am familiar with the circumstances of her life. Besides, many years of shared readings have made me fairly well aware of what matters to her intellectually. Moreover, we were brought up in the same household although it was a long time ago. So I am selecting her as a target for this discussion of the “spiritual” side of globalization. It’s in two parts: (1) Globalization does much good; (2) globalization does not do much of the harm you think it does. Part one is easier, of course.

The Good That Globalization Wrought

If “globalization” refers to anything tangible, it is to the latest reduction of national economic barriers. I say “latest” because there have been many others before — in Marco Polo’s era, and earlier than that. Goods and money cross national boundaries more easily than they did 30 years ago.

Consequently, foreign products and foreign services are more in evidence than they used to be, post-World War II. That’s true just about everywhere, including Albania and Mongolia. Not only is Pepsi nearly everywhere, as we all know, but so is Mexican beer. Tequila is giving Scotch a run for its money on world markets. Even French goat cheese is not hard to find anymore. That’s the result of various kinds of international (global) specializations that could not have been established before, because of national trade and investment barriers. French cheesemakers are not stupid. They will not expand their operations to produce cheese in larger quantities if their product is stopped or impeded at the border of many countries. Even French goats know this.

As the textbooks explain endlessly but largely pointlessly, economic specialization raises everyone’s standard of living, though not necessarily equally. (This is not a discussion of equality.) The improvement concerns price, or quality, or, more often, quality for price. Think about it! When Canadian vintners produce wine for Canadians, they are not doing anyone a favor, except themselves. As a result of lowered barriers, almost everything is cheaper than it was in my youth — except for cars, but they are enormously better. What I mean by “cheaper” is that it takes fewer hours of the mean American wage to buy the same object — a pair of conventional men’s shoes, for example. It also takes fewer hours of the average Mexican wage. This fact, it seems, has escaped the attention of the antiglobalization radicals.

The rise in living standards is easy to miss if you live in a rich country, because many of the goods affected account, on their own, for a small part of our expenditures, as they already did, 30 years ago. There isn’t much perceptible difference between a $3 toothbrush and a $2 toothbrush for people with annual incomes in the tens of thousands. Standard of living improvements are more dramatic in poor countries because there, they often concern life and death. The declining curve of infant mortality in the former “Third World” corresponds closely (and inversely) with the curve of rising GDP per capita. (There is a handful of interesting exceptions that are well worth studying but not germane to this discussion.) In other words, the higher the income, the fewer babies die. It’s that simple.

Yes, the enactment of the principle of international specialization nearly always causes some social dislocation. The $60-an-hour, 60-year-old high-school graduate laid off in Detroit because of the success of Korean cars is not likely to find an equivalent job soon. Be that as it may, the fact is that anything done to slow down the progress of international economic specialization (“globalization”) will cause the avoidable death of black and brown babies somewhere. I know this is grandiloquent and verging on bad taste, but it’s simply inescapable.

Globalization Does Not Impoverish the Quality of Our Lives

My sister’s spiritual malaise is harder to grasp without concrete examples. It has to do with the intangible, difficult-to-measure quality of the everyday life of the soul. It has to do with pleasures not strictly tied to money. “Psychic income” is a related concept. A specialty of the town where my sister lives provides a good example of such a pleasure. It’s lavender honey, which is produced not instead of but in addition to more commonplace varieties such as clover honey. I suspect the subconscious fear of losing such refinements also goes a long way toward explaining the poorly formulated distaste for globalization that exists among American academics and the American upper-middle class.

My sister operates an antique business in southern France. It’s made possible by the fact that, pushed by poverty, small farmers in her area have been leaving both the land and their furniture for 200 years — a fact she ignores. She lives in a beautiful town, in a dramatic site, surrounded by beautiful objects. I know that bragging about your relatives is like bragging about yourself, but the fact is that my sister has exquisite taste. In her better moments, Martha Stewart seems to have plagiarized her. Her daily life is as life is in Peter Mayle’s “A Year in Provence,” but better. By the way, the local people in her area were miserable only 50 years ago, because they could not afford to heat their houses in the winter.

My sister is afraid that “globalization” is going to make most of the beauty, most of the pleasure go away. I take her concern seriously. I wouldn’t want it to vanish either. But I don’t think it’s going to happen. And here is why. I will go to the American Midwest for a concrete illustration of why her fear is probably unfounded.

Thirty years ago, I got stuck in southern Indiana. In spite of the distance from the sea, it wasn’t all bad. The countryside is attractive. (It’s portrayed in the classic bicycling movie: “Breaking Away.”) Just across the river from Kentucky, it is a reservoir of traditional American crafts. Soon, in my exile, I became interested in patchwork quilts. I spent many Saturdays, and Sunday afternoons, buttering up old church ladies. They were the main sources of traditional quilts, which they sewed for church-sponsored contests. They were not quilting to sell, ostensibly. Yet, once in a while, if they liked you, if you flattered them enough into believing that you were a nice and respectful young man, they would part with one — for a price but regretfully, it seemed.

After a few years, I returned to California with three Indiana patchwork quilts. Each had been washed, which made it difficult to tell whether they were new or not; but all three were in good condition. Each had cost me a little over $100, in addition to much persuasion. I gave one away and preserved the two others carefully, to the point of nearly for- getting them in a trunk.

About ten years ago, quilts begun appearing in my good local flea market. Most showed no sign of provenance. Many looked inferior to my well-exercised eye. Then, both numbers and quality increased. Soon, it became clear that many of the quilts originated in China. Over the years, I have bought ten or twelve patchwork quilts at the flea market, with no interest in their origin, having regard only for their appearance and usefulness. I have to specify here that since I attend the flea market often, there is no precipitate buying of the “now-or-never” kind. All the quilts I acquired there deserved to be given away or to do service in my tastefully furnished house. (If I say so myself!)

The last two quilts I purchased at the flea market cost me less than $20 each. They were in perfect condition, but it’s possible they were slightly used. When I came home with my acquisitions, I took the trouble to place them side by side with my two 30-year old-plus Indiana quilts. There was no question that the flea-market quilts were superior in every way to those made by the Hoosier ladies long ago.

Incidentally, here are the two main ways to evaluate a quilt if you are not a collector. First comes the attractiveness of the patchwork — a deeply subjective matter, although there are canons. Second, the tightness of the stitching matters; roughly, the tighter the better, an easy standard. One of my flea-market quilts is clearly hand-stitched “Made in China.” The other, not labeled, probably comes from the same country.

Now, I know, everything you buy at the flea market may have fallen off the back of a truck; but I don’t think that’s the case here. Quilts are not worth stealing, and stolen goods tend to show up in large, grouped numbers, not one or two at a time.

So, here it is, a comparison of quality for price regarding a non-necessity that gladdens the heart, and that would surely gladden my sister’s heart: $100 in 1975 is like $400 in 2008. I paid $20 for a quilt in 2008; that would have been $5 in 1975. Let’s factor in the possibility that my flea-market quilts were used. Let’s assume further that each would have cost me three times more if it were new — $60 in 2008 money; $15 in the money of 1975. And let’s assume that the Hoosier quilters were not exactly the good-hearted Christian ladies I thought they were. Let’s suppose they charged me an extra 100% for being an outsider with a foreign accent. The regular price in today’s dollars would still have been $200 for each quilt. That’s still more than three times my flea-market cost. And that’s under the worst assumptions about my alertness and credulousness.

Any way you look at it, good quilts (by subjective judgment, but that of the same judge, with the evidence in front of him) cost much less than they used to. The fact is that more people can afford more quilts now, and they are not paying for the privilege with inferior quality.

It’s possible but unlikely that the last Chinese quilts I bought at the flea market were partly machine-made. I can’t tell for sure. I don’t care much, and nine out of ten buyers wouldn’t care either, or perhaps 95 out of a hundred. The basic qualities, appearance and sturdiness, are what count most for most people. I don’t wish to deal with the worries of real collectors here. That would require another set of metrics, which would remain questionable anyway. And I think knowledgeable collectors’ concerns are mostly irrelevant to my line of observation and even to my sister’s spiritual concerns.

There is nothing special about quilts, but they well represent an aspect of the intangible quality of life that, my sister worries, “globalization” is destroying. It’s not; it’s creating it. Her spiritual life will be fine. I know mine is.

Of course, my sister would ask, as you may ask, “What are the old Hoosier church ladies doing, now that the Chinese are making good quilts ?” The answer is that I don’t know, but I would bet they are making vastly better quilts than their mothers ever made, or something else equally attractive.

In the ’60s, my brother, who was the pioneer sort, bought one of the first small Honda cars in France. Everyone laughed at his lack of discernment. Are you following me?

French food is excellent today, in the restaurants, in the street markets, and even in the supermarkets. When I was a child, much everyday French food was downright gross. As

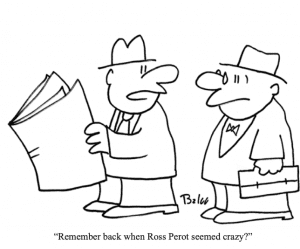

Why isn’t the accumulated wisdom of the economic disciplines sufficient to counter the lies and childish nightmares of the Left?

you know, there are McDonald’s in France today. They are few and expensive, and they serve better fare than those in the United States. I wish they would hide them better, but their presence is a small price to pay for a package that also includes gambas from West Africa and fish sauce from Vietnam.

There is more. I have not done a census but I would bet good money that there are more active painters in Santa Cruz, California, population 60,000, than in any French city three times its size. My wife is one of them. Performing a tight calculation, I am able to identify an important factor that allows her to stay home and cultivate her avocation. The opportunity cost of her doing so, given her specific marketability, is approximately equal to the difference between an American professor’s salary and his French colleague’s; that’s about 50%.

Guess which country is more open to international trade and to cross-border movements of capital? Perhaps it’s a coincidence, but it may not be. Cultural and historical factors certainly are not biased in favor of the argument I make here. Other things being equal, you would expect any French town to be more propitious to conventional art creation than any American town the same size. The number of artists has not decreased in France; it has just risen greatly in some parts of the United States. This must have helped improve the “spiritual” health of the artists and of their neighbors. And again, Americans’ increasing ability to make art has not hurt the French, except, a very few, in their ego.

Globalization, the opening of borders to merchandise, services, and capital, fosters local specialization. When people specialize, they tend to do everything they do better. The fact that they become more productive in a tangible, measurable sense has been known since David Ricardo, who lived a long time ago. The underlying thinking is that they improve at what they already did well. Another, unexpected, indirect consequence of globalization is that it also allows people to become better at some of the things they don’t do especially well, such as painting. That has to be good for the soul.

Incidentally, there is even more lavender honey, and thyme honey, and chestnut honey, in my sister’s town market than there was 30 years ago. That’s because the local hippie beekeepers can afford to experiment, more than ever, with their bees. Bless their hearts!

And, yes, you economics-trained people, I know this story does not begin to explain the doctrine of comparative advantage in its fullness and in its majesty. I don’t think I even need to say those words — words that have put to sleep generations of average Econ 201 students — in order to make my central point. Just think “quilts” and “lavender honey.”