Despite the iconic status of the double-decker bus, the black cab, and the tube, London is a city best seen on foot. The speed of modernized transportation – yes, even of public transit – reduces the city to an architectural blur: a greatest-hits list for tourist photographers, matching the tableau on the vinyl Harrod’s bags they’ve invariably bought. The city as LondonLand: monuments severed from their centuries and contexts, off the bus and back on again; speeding away, reaching whatever velocity is deemed sufficient to escape the gravitational tug of history. It’s the Stations of the Cross with Christ in a Corvette, mugging for the camera while the Cyrene tries to figure out the flash.

No one wants to see pictures of their buddies standing in front of landmarks, shots which serve only to emphasize how unimpressive are their friends, and their own lives, in contrast. Better to create one’s own meaning, engaging in the alternative to one-tour-fits-all: the unruly discipline of psychogeography. It is unavoidably subjective, necessarily irreproducible, and exactly as immersive as one wishes it to be. There’s one iron rule: pay attention. (This is both methodological and practical: the first thing most visitors to England experience is nearly getting run over while looking the wrong way crossing the street outside the station.)

In his useful primer “Psychogeography,” Melvin Coverley suggests that novices like me begin by drawing a line around the rim of a coffee mug laid on a street-level map, and then follow that circumference as closely as possible. Take note of buildings, street names, shops, graffiti, and the detritus of city life; anything that impresses itself on the mind. Upon reflection, the journey will be shaped by these considerations, and a narrative will emerge. The best writers in the field – lain Sinclair, Peter Ackroyd, Alan Moore – often plot complex routes for their walks, with themes in mind ahead of time. But they do so with full knowledge of the difficulty involved; Sinclair in particular chronicles failure as often as he does fulfillment.

Still, Coverley’s strategy – which I have found helpful exploring other cities, most recently my present academic haven in Liverpool – was far from my thoughts when I first emerged from Holborn Station into the blinding light of an unseasonably beautiful day. One of the main reasons for the popularity of the tour buses, of course, is how demanding London is to navigate, and before running rings around anything I needed to establish a beachhead. Which can be difficult, as London is (and barring another Plague, Fire, or Blitz, always will be) one of the most expensive cities in the world: a practical concern that, until lunch was acquired, pushed out of my mind any more prosaic notions.

What did not occur to me until later was that Holborn is as good a starting point as any. After all, High Holborn St, the main thoroughfare, runs largely the same course it has since the Romans built a road there, so it serves well historically. And Holborn is by tradition a bastion of journalists – and, it must be said, many, many lawyers, thanks to the proximity of both the Royal Courts of Justice and the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey).

No, what occurred to me instead, as I ate at an unremarkable cafe of the sort that mocks up historical markers saying “On this spot in 1692, nothing happened,” was the explanation for an odd behavior I had noted on the long escalator ride up from the tube. Several of my fellow detrainers boarded the escalator, and then turned around to face where they’d come from – not to talk to anyone below them, just to ride. What they were doing, I realized, was turning their backs to the security cameras that monitor everyone leaving (and, from a different vantage point, entering) the terminal. It was a small, silent protest against the encroaching British surveillance state, reducing by one the number of times their face will appear on a CCTV screen that day.

The sheer ubiquity of security cameras here is numbing: an Evening Standard article from a couple years back (http://j. mp/3ju2iV) reported that the average Englishman is monitored 300 times a day, and the number can only have gone up since then. In a clever twist, the piece also printed a map showing the location of George Orwell’s house, in relation to the 32 CCTV cameras within a 200-yard radius. An early image in Moore’s “V for Vendetta” shows a camera with a sign: “For Your Protection.” Real-life Britain has dropped that

pretense; the signs either say “CCTV Camera In Operation” or, more often, there is no sign at all. Some of my hatred for the double-decker buses, I realized, derives from my hatred of these cameras: thanks to onboard models and trophy shots, tour groups do not see nearly as much as they are seen. I took heart from the quiet rebellion of those who turned away – and just as quickly saw the futility of such gestures, when a succession of mobile CCTV police vans trundled down High Holborn.

It was the next morning when I continued my expedition, heading east on that same street toward the city of London proper. The early omens were good: at the first major exchange, Holborn Circus, I found a church of my namesake. Dating back a millennium or more, St. Andrew’s is one of

An early image in “V for Vendetta” shows a camera with a sign: “For Your Protection.” Real-life Britain has dropped that pretense.

many churches rebuilt by the great Christopher Wren – not because it went up in the Great Fire, but simply because it was falling apart and he was on an absolute tear. Three centuries later, the Germans gutted it in the Blitz; it was rebuilt stone for stone to Wren’s design. This resilience to adversity and tyranny found another appropriate icon on Holborn Viaduct just beyond: a statue of a proud, crowned woman emblazoned “Commerce.” The juxtaposition spoke of the heroism of everyday people, oft beaten down but never quite broken, going about their business the best they can despite the intrusions and depredations of the state.

Of course, just down the street is one building that has at many times embodied state intrusion and depredation: . Old Bailey, the monumental criminal court built on the site of Newgate Gaol. (For the horrors of Newgate, see Ackroyd’s essay in his “London: A Biography” or just about any Dickens novel.) Old Bailey, too, features a statue, a golden Lady Justice sitting atop the courthouse; significantly, she is not blindfolded. Appropriately for the Britain of today, this Justice sees (or attempts to see) alL Alan Moore seized on this identification of Justice with surveillance state, when his V climbs Old Bailey to explain to the statue that he is leaving her for his new love, Anarchy – immediately before blowing up the place.

Another alarming note is sounded – until the destruction of the prison, literally – by the church opposite the court, St. Sepulchre-without-Newgate. There hung the “bells of Old Bailey” from the nursery rhyme “Oranges and Lemons,” which throughout “1984” runs through Winston Smith’s head as a reminder of a “lost London that still existed somewhere or other, disguised and forgotten.” But those bells rang to signify the execution of a prisoner; as shown in the closing couplet that Julia supplies: “Here comes a candle to light you to bed / Here comes a chopper to chop off your head!” Though his forecast of a televisual surveillance state was prescient, if a bit premature, Orwell knew all too well that even in Winston’s lost London, the people were subject to the gaze of the state.

Old Bailey is overshadowed by another cathedral; in one of the happy coincidences that mark a walk gone well, this one takes its name from a saint famous for an episode of blindness, and a miraculous recovery of sight. St. Paul’s is the preeminent cathedral in England, and one of the finest in the world: Wren’s crowning achievement, the building is itself crowned by a dome bigger than any but the Basilica in Rome – a dome, remarkably, that can be scaled all the way up, 570 steps to the Golden Gallery at its peak. As they go, the staircases get vertiginously steep; it is no mean accomplishment to attain the summit. But at that height, one can reclaim the vision commandeered at ground level by Lady Justice and her CCTV armada.

The cathedral’s Baroque design drew complaints at its unveiling that it smacked of “popery” – or worse, heathenism. In Moore’s “From Hell,” St. Paul’s sits at the center of Jack the Ripper’s psychogeographic pentagram cut across the city, culmination of a Masonic ritual reactivating the prison that chains the gods of the pagan past to England present. The mark of the Ripper’s bloody success is the vision he receives, not only of London lost, but also of London yet to come. For good and ill, St. Paul’s represents the unfettering of the imagination: human creativity at its peak.

The descent from that pinnacle is horrifying, both physically and metaphorically. Directly south ofSt. Paul’s, on the far bank of the Thames, is the counterweight balancing that mad mystic mound: the concrete-bunker power station in which the Tate Modern art gallery has taken up residence (squatted, really) following an amiable split from its more elegant partner, Tate Britain. The stretch of the river separating the two is spanned by the Millennium Bridge (see photo I), one of a half-baked batch of projects London cooked up in the chiliastic fervor leading up to Y2K. The Bridge was open for precisely two days in 2000 before it had to be shut down for two years of renovations; however, unlike its ill-starred sister project, the Millennium Dome (for which Sinclair reserved some of his choicest bile), the Bridge is still standing a decade later.

Still, classical engineering it is not, and as such it is an appropriate introduction to Tate Modern. The museum devotes itself to art since 1900, and holds at least a work or two of almost every major international artist of the past century. Yet these galleries are always subordinated to one major installation in the massive Turbine Hall, a three-dimensional cement canvas given over to a new artist each year. An exhibit on this scale cannot but set the mood for the rest of the museum; in past years it’s ranged from neurotic (Doris Salcedo’s “Shibboleth,” a slowly-widening crack stretching the length of the building”) to giddy (Carsten Holler’s “Test Area,” a series of twisty slides connecting the other floors to the Hall). This year the Turbine Hall is hosting Miroslaw Balka’s “How It Is,” which, conveniently for my theme, depends for its effect on the utter denial of vision. The work is a two-story-high metal cube lifted up on steel girders for supports. The cube is open on one side (facing away from any direct light source), and there is a ramp leading up to the inside, which Balka lined in black velvet to deepen the darkness.

In short, the installation is an anti-St. Paul’s. The climb is gentle and graded rather than hard and rugged; at the end, instead of the best views in London, one finds an abyss. From the outside, perched on its girders, the cube appears unsteady, unlike St. Paul’s which famously repelled direct hits from German bombers during the Blitz. Balka has said that the exhibit is meant to evoke the feeling of those Jews packed into train cars and sent off to concentration camps; it fails at this, partly because everyone who goes in knows they’re coming out, and partly because the ambient light, even on a typically grey British day, cannot entirely be eliminated. But the

The exhibit is meant to evoke the feeling of those Jews packed into train cars and sent off to concentration camps.

first moment inside is genuinely unsettling: almost everyone approaching the exhibit hesitates at the top of the ramp before stepping into the blackness, as if reminding themselves that even Tate Modern wouldn’t allow an artist to lead patrons to the slaughter. In its ideal conception, at least, “How It Is” represents the most extreme form of the surveillance state, when surveillance is no longer necessary because there is nothing left to survey.

Southwest of Tate Modern I picked up a sandwich and a few of the day’s threads near Waterloo Station, the enormous railway junction which has for decades served as a rendezvous point for south Londoners. I had thoughts of striking northwest, across Waterloo Bridge (which unlike the Millennium had held up for a century before getting closed down and rebuilt). From the Bridge one can see the entire bend of the Thames; it is the one place ground-level where the view isn’t constricted – though it is, of course, monitored. But somehow that path felt incomplete, off. In consulting my map, I saw I’d thus far described a semicircular arc; taking the Waterloo Bridge would draw a sharp diameter across the enquiry. There were elements that could not be resolved going north. It was the wrong shape.

Every psychogeographic expedition runs into the doldrums eventually, and I had hit mine. (Even writing about it now, recreating the journey in full awareness of how it will finish, I find it a struggle to get the words on paper.) Backtracking mentally, I recognized that upon leaving Tate, I’d stopped paying attention – I’d drifted aimlessly down a succession of unremarkable streets, vaguely wanting food but not much else. The unease had not settled in, though, until I’d turned up Waterloo Road toward the station; retracing my steps, I continued on Westminster Bridge Road instead; something was pulling me west.

Partly it was that damned cube. By Balka’s own admission, he had simulated me being railroaded off to my death. Allowing the symbolic rebirth of walking back out was all well and good, but the bit of me meant to die in there needed burial before I could cross back over the river, and by turning up Waterloo Road I’d missed the place for it: the London Necropolis Railway. Established to get corpses and mourners out of Victorian London and into the country where there was actually room for them, it ran at least intermittently until 1941, when all but the entrance was demolished by bombs.

This combination of trains, cemeteries, and German aggression seemed sufficient to lay to rest the specter Balka raised; leaving two pennies by the gate to pay for passage, I made for Westminster Bridge. My renewed focus came not a moment too soon. For it is from Westminster, and specifically the Palace of that name, that the surveillance state emanates. Between the CCTV cameras and the round-the-clock tourist throng, the Westminster complex may be the most photographed place on earth (see photo 2).

And yet, it is a place that inspires complacency: four centuries later the failure of the Gunpowder Plot lingers over it. In Moore’s graphic novel, V begins his vendetta by finishing the job Guy Fawkes and crew started – but the building V blows up is an empty shell, less an embodiment of the fascist state than a relic of a London disguised and forgotten. The movie adaptation foolishly makes this the final act: Big Ben blowing up to the nIBI2 Overture” somehow manages to come off as anticlimactic – nearly as big a letdown as the original Plot itself. (For more about “V,” see the reviews by Jo Ann Skousen and Ross Levatter, June 2006.)

But as I looked over the Palace, and especially the Abbey just opposite, I found the Westminster complex sadly lacking as a symbol of modern-day tyranny. For the tyrants of earlier ages, sure, this palace upon the Thames lived up to its reputation as the “heart of darkness” for many a subject people, in the days when English oppressors were magnificent, and ambitious, and creative in their cruelty. Today’s tyrants, though, are unworthy of such a grand structure: creatures of such limited intellectual horizons that they must rely on others’ technologies to claim any sort of vision whatsoever; so lacking in discernment that to see anything, they must see it all. The emblem for this style of governance is not the elegant, imposing Palace; much less is it Westminster Abbey, burial ground of kings and poets.

No, the British surveillance state is best represented by an edifice – meant, appropriately enough, as a short-term attraction, but now held over indefinitely – installed just on the far bank of the Thames: the giant Ferris wheel called the London Eye. Towering over even Big Ben, it offers to anyone willing to wait in line for the better part of a day a pan-optical view of the city. From such a height, there is no separation between places (and thus no connections between them, either), only one vast whole. Unlike the vistas available from S1. Paul’s Golden Gallery, experienced only after a Dantesque climb through successively rarefied genius, the London Eye offers a slow plod through thin air. Riders in glassed-in pods take identical panoramas, paying for the privilege of becoming part of the surveillance apparatus.

It was this structure, I realized, that I’d been skirting round all day; first peeking over buildings at the Millennium Bridge onward, then close up on the edge of Waterloo Station (see photo 3).

But as with many monstrous things, it did not reveal its true form till nightfall, when the rim lights up bright red, evoking, of all things, Tolkien’s description of Sauron: “a great Eye, lidless, wreathed in flame” (see picture 4, the color of course will have to be imagined).

I stood on the edge of the Victoria Embankment, staring back at it, challenging it, but it is relentless – its pace never more than a creep, so that its interchangeable passengers can be processed as it continues to turn.

My day’s final steps became clear: I needed to complete my loop, matching the Eye’s circuit with one of my own – encircling it in the history its views obliterate. For the truest arc, I would have to cut back down to Westminster and make my way up Whitehall, but marching up a street with governmental departments looking down on me from both sides seemed a bit incongruous with my aim; instead I walked further up the Embankment to pay my Photo 3 respects to Cleopatra’s Needle, touchstone of many a psychogeographic ramble, including that of Moore’s Ripper in “From Hell” – nothing reasserts a sense of historical awareness like a 3,400-year-old Egyptian obelisk. From there I turned toward Trafalgar Square and another obelisk, this one native in origin: Nelson’s Column. In between runs Northumberland Avenue, itself a product of historical disappearance, the name being all that remains of Northumberland House and the other great manors that once lined the banks of the Thames.

Trafalgar Square obviously is one of the great tourist parks of the world, and a powerful symbol of all things English; had Hitler’s invasion plan succeeded, he had settled on Nelson’s Column as the trophy he wished to carry back with him to Berlin. Standing at the base of the pillar, one can see among other sights the National Gallery, St. Martin-of-the-Fields, the

The greatest tragedy of “1984” is not the totalitarian state, it’s the complicity, the outright eagerness of people in perpetuating it.

Strand, and the Mall leading down to Buckingham Palace. But I had eyes only for completing my circuit; with the darkness closing in there was increasingly little to pay attention to without attracting the gaze of others. Heading north of the Square, up narrow St. Martin’s Lane and past a series of posh West End theaters, I began to feel that I might yet escape the Eye. But it wasn’t till I crossed back over High Holborn and closed my loop that I saw the proof of it: the beaming portico of the British Museum, repository of over 12,000 years of human history.

When I arrived, the museum proper had closed, but the renovated Great Court wasn’t open. Once an open courtyard, the Great Court held the famed round Reading Room whose patron list was a who’s-who of the 19th-century literary world (most often noted in this context is Marx, who assembled the basics of communist theory from a desk in this library while steadfastly refusing Engels’ invitations to tour the factories he owned). Today, with the Library having moved on, the Reading Room hosts major exhibitions; the Great Court, meanwhile, has been completely transformed. Now ingeniously roofed over with computer-designed panes of glass, each one different, the aim of the new floor design is that with every step, the view will change and new objects be revealed to the eye. The courtyard functions as a microcosm of the city

itself, demanding to be explored psychogeographically – and since hundreds of tour buses drop off thousands of tourists at the British Museum every day, there is guaranteed to be one spot on the itinerary where they will have to engage with their environment; they will not be able just to wait, rooted to one spot, and have it flash before them.

For it’s that complacency, that passivity, which is the most dangerous aspect of the modern surveillance state. The greatest tragedy of “1984” is not the totalitarian state established in Britain, it’s the complicity, even the outright eagerness, of the people in perpetuating it. In America as well as Britain there is a swelling conflict over the right of everyday people to document the day-to-day dealings of those in power. The authorities, of course, wish to have total access to our lives while working in complete secrecy: every camera they take, every video they erase, every website they force offline through the application of money and lawyers is a bluff on their part, a gamble that we’ll settle for seeing only what they wish to show us – that well be content to stand with the government line, paying them to see through their Eye.

Rebelling against this doesn’t mean donning Guy Fawkes masks and blowing up landmarks (though I do get a kick out of the story each month or so when some fed-up motorist takes a bat to a traffic-camera array), but we can emulate V in one way: our insistence on seeing rather than being seen. It is vital that we keep our eyes open and, whenever possible, turn the oppressive tools of government back against it. In 1997, visual artist Gillian Wearing won the Turner Prize

When the hour is up, one policeman utters a sound somewhere between a gasp and a scream, so great is his relief at being free from the burden of surveillance.

(arguably the most prestigious English arts award, administered by Tate Britain) for her work”60 minutes of Silence,” an hour-long Videotape of a group of police officers whom she’d asked to remain completely motionless during the shoot. It looks at first like a still photo, but as the hour wears on, the shufflings, scratchings, and throat-clearings become more and more evident; when Wearing finally announces the hour is up, one policeman utters a sound somewhere between a gasp and a scream, so great is his relief at being freed from the burden of surveillance.

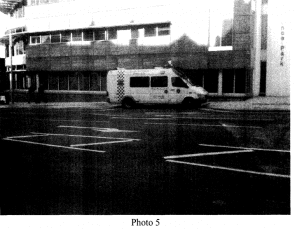

Yet that is the same burden that we as citizens are asked to bear hour upon hour, day after day, without a hope of anyone telling us our time is up. Enough! In an age where nearly everyone carries around a device equipped for multi-megapixel image capture, there is no reason that we should not be able to document the presence of a bank of traffic cameras, or a mobile CCTV van idling on the side of a calm street for no apparent reason (see photo 5). And in the meantime, there are other small, symbolic acts of rebellion available to us.

On my way back from London, I boarded the escalators backward.