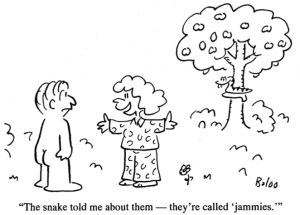

At the age of twelve I become an atheist and have remained so ever since. I say this in order to make it clear I’m not a creationist. Indeed, if I were looking for a religious account of the origin of the world I think I would turn to the earliest such accounts in Mesopotamia and Egypt in the grounds that they are closer to the origins and hence more likely to be accurate.

Genesis, although accepted by the Jews, the Christians, Islam, and the Mormons, is at least 1,000 years younger than the Mesopotamian and Egyptian tales. Indeed, part of the book of Genesis is lifted from Mesopotamian legends.*

his paper is an attack on the work of Darwin and the synthesis of the 1930s but it does not provide a replacement. Obviously, I think a replacement is highly desirable, but I have only wild speculations. One purpose of the paper is to stimulate thought in hopes that a new and better theory will be designed. I should say, however, I’m not alone in my discontent. A Nobel Prize recipient in the appropriate sciences, (Crick)** and a man knighted for scientific achievements, (Hoyle)* albeit in astronomy, not biology, have written strong attacks on the current theory.

I will turn to them in due course, but first let me explain the problem which makes me and them dislike the current theoretical position. The problem is that instead of a steady change with species being gradually replaced there are severe gaps in the fossil record; indeed, there are only gaps. Darwin

*See. The Archives of EbLa, by Giovanni Pettinato with an afterword by MItchell Dahood, S.]., Doubleday, 1981. The afterword is a careful sur- vey of similarities between the Old Testament and earlier Middle Eastern writings.

**The Astonishing Hypothesis, by Francis Crick, Simon & Schuster, 1995.

was fully aware of this and he said that the fossil record was incomplete, which it was, and that there would be much more digging, which there was, and this would change the picture to one of continuous evolution. Unfortunately, this last has not happened. If anything the process has been in reverse.

Lee Berger, a man who has devoted his life to straighten- ing out the history of the human species, says, “In fact the more fossils come to light, the less our family tree appears as a magnificently tall Redwood with well-defined branches thrusting toward the pinnacle of human achievement. Rather it resembles a scraggly thorn bush whose spiked and twisted interwoven limbs would be hazardous to unravel.” **

The same thing has happened with other animal groups. When I studied biology in high school long ago, the textbook had a diagram showing the development of the modem horse. In essence it showed the main trunk of a tree with various species from eohippus to the modem horse arranged more or less vertically. Today, textbooks show either a bush or tree with many branches and the various species on the ends of these branches. The direct ancestors of the horse or the previous species are not shown because modern biologists have improved their knowledge of the various species. Far more fossils are now available, and paleontologists now realize that

**: In the Footsteps of Eve, by Lee R. ,Berger with Brett Hilton-Barber, Adventure Press, 2000, p. 18. See also p. 67.

the earlier ones are not direct ancestors of the more recent ones. They are cousins rather than grandparents. Evolution may have been continuous with many intermediate types simply not having been preserved, but to believe this is a matter of faith, not science.

To return again to my far distant education, mutations and their effect on evolution were discussed in essentially a gradual, continuous model. Some individual member of a species would have a mutation. As was pointed out, the overwhelm- ing majority of such significant mutations were not improvements. Occasionally however an advantageous mutation would occur and the individual would pass it on to its descendants..In addition, not all members of a species have exactly the same genes. The vast number of radically different dogs, which has been produced by selective breeding, illustrates that. Still, the range of variation that can be obtained without

Darwin said that the fossil record was incomplete and that there would be much more digging and this would change the picture to one of continuous evolution. If anything, the process has been in reverse.

mutation is limited. No breeder has produced a cat·out of canine parents.*

To further simplify the simple Darwinian-Mendelian model, after a mutation, the product, if viable, would not only preserve that mutation but also occasionally have other mutations. Further, that particular mutation might match well with variants already in the gene pool. These descendants in tum would have mutations, most of which would be disadvantageous, but some of which would be advantageous and lead to further changes. In time the original species would be replaced by an improved variant, which, since it was improved, could either out-compete the original model or occupy a· special niche alongside the original species. The change, however, would have been a gradual consequence of many small changes, which ended up as a large total change.

Although Darwin did not know about mutations or Mendel’s work, the synthesis of the 1930s created an apparently rigorous model, whi<zh had the same result. It also called for gradual change through the accumulation of small changes. Unfortunately, this also fails to account for the extreme dominance of gaps in the fossil record. Punctuated equilibrium, which I will discuss shortly, is an attempt to do that. It is, of course, possible that the gaps will eventually be filled by more digging. Certainly the number of fossils which have been dug up is but a small.fraction of the total number existing in various parts of the earth. Still, it seems unlikely that. we would not have many cases of gradual development in various species from the fossils we have now if the gradual change model fit reality.

Darwin pointed out the immense changes that selective

*I will here and later in the paper ignore the complications involved in sexual transmission. This is not because I believe they are unimpor- tant, but because discussing them would not fundamentally change the reasoning and would involve a good deal of extra verbiage.

breeding has made in domesticated species. But these changes have not originated a new species. In my college biology class it was pointed out that a Great Dane could not mate with a Chihuahua. Nevertheless, we do not consider them separate species. Perhaps some of the modern engineered strains have changed enough so that we would consider them separate species from their ancestors. Perhaps, but I doubt it.

Now, of course, we can make genuine changes by adjust- ing the DNA. It doesn’t seem likely that we could, even in the future, produce a new species by changing one or even a few genes. The change would have to be more radical. Altogether, the gradual change model in its conventional form doesn’t seem adequate, and we need something new. Perhaps one of my readers will provide it.

For now, however: consider the cats. To a layman they seem to differ mainly in size. The lion looks very much like a large cat. Specialists recognize many more subtle differences both in structure and behavior. But the similarities are astonishingly great, and cats are all believed to be closely related and descended from some ancient common ancestor.

Nevertheless, they are separate species and there are no gradual transitions from one to another. A lion and a leopard are both carnivores although their behavior patterns are quite different. Most biologists do not ask why we do not find intermediate individuals. This does not represent a lack of curiosity, but knowledge of the reason why there are none. Each member of the cat family occupies a separate· niche, and apparently there are no niches intermediate between the one occupied by the lion and the one occupied by the leopard.

But this raises the basic question about evolution. If a leopard

The account in Genesis is easy to poke fun at, but the account of modern biology depends to a considerable extent on faith also.

had a mutation which changed one of its genes to the cor~ responding gene of a lion, this would move it out of its niche and make it less fit to survive. We do not know how many genes differ between the leopard and a lion. Until this point has been straightened out I will assume that there are 20. I do not have any idea whether this is even approximately correct, but some number is necessary for the next few paragraphs.

Once the first mutation had occurred there could be more mutations, but there’s no reason to believe that mutations of this sort would be commoner than in any other leopard. Further, there is no reason to believe that these further mutations would be in the direction of making a lion. The process of mutation is generally thought to be random, with the selection among mutations being imposed· by the environment. Since we observe no gaps between the lion and the leopard, it seems likely that there is no available niche between the ones occupied by the existing species. Any mutation that worked to change the lion-leopard situation would be anti-evolutionary and would probably be selected out.

The illustration on this page is an attempt to show these niches graphically. Each peak is a particular niche and the lines surrounding it are intended to be· about one mutation apart, with the fitness of the niche declining as you move away from the peak. The line connecting the two peaks is intended to show how difficult it would be for a series of mutations to change one species into another. This particular line is a simplification of what we might find if a super-skilled human breeder were making a deliberate effort to get from one species to another, say, a lion to a leopard. Natural transmission would not involve such a steadily directed chain of mutations. Nor could it aid getti~g through the valley between the two peaks.

Note also that there is another peak in the figure, which is another niche. This niche is unoccupied. We know that there are such unoccupied favorable niches because from time to time a species is brought in from some distant place and flourishes. If a particular individual gene were able to persist even though it offered nothing in the way of improved survival, the individuals who had it would be subject to further mutation. These mutations would essentially be random, but occasionally one would lead further toward another peak. This moves its possessor even further down the mountain from its original peak. It should therefore lead to even lower fitness. Only after perhaps ten mutations in that direction would further mutations, if they were lucky, lead to the second peak. Granted the fact that all mutations are essentially random, such transition seems impossible and, of course, we do not see it.*

This is a problem that Darwin thought would be

solved by further digging. It hasn’t been solved. Among the general relatives of your pet cat there is the sabertooth tiger. Except for its very large canine teeth, to the layman it appears very much like a modern tiger. Since paleontologists frequently explain its extinction on the grounds that it was stupid, I presume that its braincase was relatively small. Interestingly, it lasted on the American continents much longer than on the Eurasian landmass. Presumably, the competition was less severe in America. Anyway, it overlapped humans on our continent and lived long enough to be trapped in the tar pits of La Brea.

*Dawkins in River Out of Eden says, “Unlike human designers, natural selection can’t go downhill- not even if there is a tempting higher hill on the other side of the valley.” Basic Books, 1995, p. 79.

But to repeat Darwin’s question, Why do we not have a continuing series of skulls with gradually shortening canines? The fossils simply move from the sabertooth tiger to the more modern tiger in one step. This raises Darwin’s question in a particularly vigorous way. I should say that it is as hard to answer that question by using the intelligent designer theory associated with William Paley and some moderns as by using Darwin’s theory. If there were an intelligent designer, why would he produce the sabertooth at all? Why not go directly to the modern tiger?

The orthodox answer to this problem is that creation did move gradually, but the intermediate species have not yet been dug up. This rather fits my figure, since species in the valley between the two peaks would have low survival ability; hence not many would be in existence at any time; hence few skeletons would be available. This assumes that the valley is the right depth to make survival difficult but .not impossible. Since we have no measurements or even any way of making measurements I cannot say this is impossible, but it certainly seems unlikely.

I should, perhaps, pause here and turn to the public debate on the subject. The professional biologists normally desire that people on the other side, mainly but not entirely believers'” in the book of Genesis, be prevented from teaching their doctrine even in the form of a debate. I think this is motivated by the type of questions raised above. The account in Genesis is easy to poke fun at, but the account of modern biology depends to a considerable extent on faith also.·The gaps in the evolutionary record are real and sizable. To feel that they will eventually be solved, as I do, is a matter of faith, not science. I think this particular belief comes closer to science than the book of Genesis, but nevertheless, my belief is not science.

Paley, an 18th-century doctor of divinity, used a rather similar argument to imply the existence of an intelligent designer. He, being a minister, had no doubt about who that intelligent designer was. Belief in an intelligent designer does not entail belief in the literal details of the creation account in Genesis. St. Augustine said that the early books of the Bible were written so that the simple people of those times could follow them and the more sophisticated people of the fifth century A.D. could put more sophisticated interpretations on the language.* Presumably, we are even more sophisticated and hence can deviate even further from the literal words of the Bible. while still remaining Christians, Jews, Muslims, or Mormons.

Unfortunately, I do not believe in the intelligent designer, certainly not the God who purportedly wrote the Bible. Thus I am more or less barred from Paley’s answer. As we will see below there are other people with excellent scientific credentials who are not believing Christians but who nevertheless believe in an intelligent designer. In all the cases I know of, and that is few, this intelligent designer is a civilization on some planet circling a far distant star.**

But let us look at Paley’s argument which is simple and convincing. He points out that if you stumbled on a· watch while walking through a field, you would not feel that it was an accidental, and more complicated than the usual rock. You

Step-by-step, mutation-by-mutation change would at first disadvantage the entity, and this would be so even if a long chain of such mutations were likely to benefit it.

would see in it obvious evidence of design. This is, of course, true. He then goes on to say that because the human eye shows exactly the same evidence of intelligent design, it could not have originated by chance.

Dawkins took up the challenge and in Climbing Mount Improbable. explained how a very large number of very small steps could move toward the human eye. Further, he argued that each of the steps would have evolutionary value. In other words, in our figure we started in the valley and went up.

But even in respect to his simplified model, it’s not obvious that Dawkins is right. If there were one light-sensitive cell on the outside of some animal, it is not at all obvious that having two would be much advantage. Dawkins jumps from one cell to a discussion of how a small colony of such cells might form a pocket and hence be on the first step toward an eye. Since the purpose is to get some idea of the direction of a light source, a bulge would seem to be equally likely. But the movement from one light cell to a cluster is more difficult evolution- arily than having a cluster form a pocket or bulge.

There is, however, a more serious problem. A cluster of light-sensitive cells on the outside of some animal would simply be a handicap unless it were connected to other parts of the animal in such a way that the animal responded to light sources in an evolutionarily desirable way. If we just had a number of light cells, they would necessarily reduce the fitness of the animal unless further changes to collect the information, process it, and take action were made. In other words, the development of a number of light-sensitive cells, or for that matter one cell, would actually be moving its bearer down into the valley of our diagram until the development of further apparatus would move it up toward another peak.

.A step-by-step,·mutation-by-mutation change would at first disadvantage the entity, and this would be so even if a long chain of such mutations were likely to benefit it. Although most biologists don’t talk about this matter, it has worried a number of leading scientists. In 1954, Ernst Mayr “proposed that a peripherally isolated founder population could undertake a considerable ecological shift and genetic restructuring and become the ideal starting point for a new lineage.”f.f. Originally this was referred to as the “hopeful monster,” but that terminology is now passe.

Normally today it is called”punctuated equilibrium” and credit for developing Mayr’s idea goes to Niles Eldridge and Steven Jay Gould. We may, however, just as well start with the hopeful monster and then take up punctuated equilibrium later. Both of these ideas are occasionally mentioned in the biological literature but in a rather sketchy fashion. Since I am not a professional biologist I may have missed a more elaborate account, but the reader will, I hope, excuse me if I proceed with my best understanding of the matter.

Any niche may have in its outskirts small areas, which are partially cut off from the main niche. Strictly speaking the small areas should be thought of as pockets in the multidi- mensional niche space, but it’s easier to think of this matter if we confine it to a real, but simplified model, the Galapagos Island archipelago. Consider the finches that Darwin found

Ptolemy worked out a theory of the solar system that was in complete accord with the facts as then known, and remained in accord with the facts discovered in the next 1,200 years. Today we look back at his work as intellectually a great achievement but also as wrong.

there and collected. Clearly the finch on the South American continent was the origin of these other tiny species found only on different islands. What had happened is fairly obvious. The islands are far off the mainland and finches normally do not spend much time over the open sea. Some of them, however, by accident reached the Galapagos and settled down.

In each case the particular finches that arrived would be a small sample of the mainland finches and hence would not bring with them all the varying genes found in the whole species. Each one was an accidental example of selective breeding. Further, the environment of each island was different from the others and quite radically different from the main- land. Under the circumstances, mutations that would not be viable on the mainland might be preserved on an individual island. Further mutations could then take place, and eventually a separate species viable on that island, with its reduced competitive pressure and different environment, might develop.

Eventually a breeding pair of such a species might return

to the mainland. Probably they would not be able to compete and would be eliminated. One can readily imagine that at least occasionally one of these small, semi-detached environ- ments might produce not only different but also improved species, which could then successfully invade the mainland. These true-breeding strains would be the hopeful monsters. When they first began to mutate they became less fit and hence were the monsters, but with further mutations some might become a new and successful species. Using our diagram – in their isolated island they got through a series of mutations, which would have been deep in the valley. If they were still on the mainland they would have been eliminated in the valley stage.

Clearly this could happen, but note its high improbability. Only if there were very many of these small pockets semi-

Why do we not have a continuing series of skulls with gradually shortening canines? The fossils simply move from the sabertooth tiger to the more modern tiger in one step.

detached from the main environment and in at least one of them the right set of mutations occurred in the right order and then the semi-detachment dissolved, can the theory explain evolutionary progress. Further, the new creatures would have to be at least viable, if not optimal, on the island and markedly better than the native stock on the mainland. The theory, if true, provides an explanation of why there are few intermediate fossils, but it does not explain why there are none. Assume that the deviant species were only one percent or even one-tenth of one percent as common as the main species. We would find relatively few fossils but, given the total number of fossils we have, we should have at least some of these.

The other problem is the probability or improbability of the process. To make it work, one would need tens of thousands of small environments at least one of which had the fortunate chain of mutations. Calculating the probabilities puts you up in more or less astronomical numbers; hence if we thought of this as occurring at a particular time, we would regard it as functionally impossible. On the other hand, if we consider the fact that many of the finch species on the mainland have existed for millions of years and the hopeful monster could have developed at any time, the improbability becomes less. It might be a very small chance during anyone century, but we have many centuries and that might, emphasize might, make up for the otherwise very low estimate about the likelihood of this happening.

Let us go to punctuated equilibrium, which in a way is merely a generalization of the original idea by Mayr and has received more publicity than the hopeful monsters.! It apparently is disbelieved by most biologists, but ideas normally start with minorities, and this theory may be correct. I don’t think it is, but it is at least possible.

The existence of species unchanged for very long periods of time is the equilibrium of the Eldridge-Gould theory. The punctuation is the sudden radical change. What brings on this sudden radical change is not very clear. It might be a radical change such as the earth being hit by a comet. Many biologists think that such a change did occur at least once, and got rid of the dinosaurs. There is also speculation about other mass impacts at various times. Normally, however, changes in one particular species are not highly correlated in time with those in many other species, which would rule this particular mechanism out as an agency of evolution.

Suppose then that one particular finch which developed on Darwin’s islands returned to the mainland and replaced the original finch species. The replacement might take.a rather short period of time, geologically speaking. Thus if this sequence of events occurred, we would have an example of punctuated equilibrium. In collecting fossils we might or might not find an example of the intermediate stage. If the replacement was fast, and it might be, intermediate stage fossils would be rare. But note that to say they would be rare does not mean they would be totally nonexistent, which is the present situation.

The theory does, however, explain the almost complete absence of any fossils from the intermediate zone between long periods in which there is little change. Gould is an expert on snails and has found areas where tens of thousands of years of sediment have accumulated with exactly the same snails in each level. He has not found a lot of clear-cut cases in which a fairly radical change occurs in the same part of the deposit as the long period of stability.

Obviously this sort of thing could happen. But to put the main emphasis in evolution on obviously rare and very special phenomena seems unwise. Consider the necessary conditions: small special environments for which access from the main environment is possible but restricted, coupled with the special environments different enough to exert evolutionary pressure but not different enough to make the product nonvi- able in the main environment. To repeat: This is obviously possible but doesn’t seem likely as a mass phenomenon. I think the reason that the hypothesis has been accepted by biologists is that they simply have no other explanation. It’s not a good explanation, but it is possible to believe and a poor explanation is better than none. Still, if the only explanation that has been invented is poor, this is an argument for searching for another explanation.

Medicine is part of biology and there are two famous examples of the acceptance of unlikely theories in medicine simply because doctors couldn’t think of another. The first of these is the general theory of “humors” which dominated Western medicine for almost 2,000 years. If you had criticized this theory to a 16th-century doctor, he would’ve asked you for another theory and in the 16th-century you could not have answered. Fortunately, not everyone was satisfied and eventually the search led to a solution. Most of us would not be alive today if the new theory had not been developed.

The second false theory is Freudianism. For a considerable period of time this was the only theory of mental disease. Interestingly, although it is no longer much believed, it has not been replaced as a theory. We have discovered a number of drugs which suppress symptoms of mental disease although we don’t really know why. Still, it is better to be without a theory than to believe firmly in the false theory.

I am, in essence, saying that we should be looking for a new theory of evolution. I believe that the only reason for the present acceptance of punctuated equilibrium, in so far as it is accepted, is simply the absence of a better theory. I suggest that in this case a search is desirable and that the existence of a false theory, together with widespread acceptance of it, makes such searches feeble and unlikely to reach a conclusion.

Let us now go to the intelligent-designer theorists. A popular representative of them is Michael Behe* who is rather conventional in that he believes that the intelligent designer was God. I should immediately explain that he does not believe the book of Genesis is literally correct in all its details. He doesn’t mention S1. Augustine and his view that the early

The only reason for the present acceptance of punctuated equilibrium, in so far as it is accepted, is simply the absence of a better theory.

parts of the Bible were not literally true. He may in fact never have heard of him. He does, however, believe that the funda- mental design of cells and single-cell animals cannot be explained by evolution. He is apparently willing to accept that evolution works at least sometimes at higher levels.

To interject a bit of my personal history, when I was studying law at the University of Chicago, all students of the law school were required to take a famous course taught by the president of the university, Robert Hutchins, and his intellectual sidekick Mortimer Adler. This was mainly a course in philosophy of species, a subject on which both of them were experts, but it also dealt with evolution. They argued that while Darwin could explain most species changes, there were certain radical changes, one of which was the origin of humans, which required divine intervention. I was not converted and fortunately the final exam did not contain a question on this particular part of the course. I believe however that this view was quite widely held among philosophers of a religious inclination. Thus Behe is in good intellectual company in believing in evolution in some cases and not others.

His argument however is rather above my head. He deals with the internal functioning of single cells, a subject on which he, a distinguished expert on single-cell animals, can easily lose non-experts. His argument deals with the internal functioning of these tiny organisms and I found it convincing, but I doubt my judgment in this field. One point he made, however, I thought was very strong. He said there was no evolutionary explanation of the development of these single-cell animals. Indeed, he devotes considerable space to discussing places where such explanation would be expected and pointing out its absence. For example the Journal of Molecular Evolution** doesn’t really offer any explanation although there are many articles whose titles rather suggest such an explanation. Mayr himself says that cellular biology is almost entirely descriptive. But the reader must go to Behe for a complete discussion. I have already admitted that he is rather above my head.

Behe’s exploration of life on the micro-level has at least the function of reminding us of a subject generally neglected by the evolutionary literature. I should like here to point out another defect in the evolutionary literature. Surely the single-cell living entities must have developed from yet simpler organisms. This would turn us to viruses. I’ve never seen an evolutionary account of the development of the cell from these simpler organisms. Indeed almost all of them, which we know about, are parasites on larger species. They make use of the cell machinery of larger animals to produce their descendants. So far as we know there are no totally free-living examples. A distinguished biologist in a letter to me said: “The history of what happened before the bacterial celled stage is a mystery that would be solved if earlier branches of the tree were known.” That is, of course, true. All mysteries would be solved if the answers were known.

That absence of free-living examples loses importance when we realize that almost all of them were discovered because they cause diseases in larger organisms. Thus the evolutionary history of life begins with the single-cell entities. We can feel confident that if evolution is correct, small or less elaborate entities preceded the cells. But this is a gap, a blank space, in our knowledge of life. It is sometimes argued that at this level the things which we can see with an electron micro-scope are not really life. Still, they must have preceded the liv-

The theory of distant origin does not solve the basic problem of the origin of life itself. It would presumably be as hard for life to start on another planet as on earth.

ing cells. Perhaps, although those that now exist are parasites, the free-living ones, which preceded the cells, were destroyed by the cells or abandoned free life and became parasites.

It is however a logical necessity that things simpler than the cell gave birth to’ the cell – if we believe in evolution. For a good discussion of the possible origin of subcellular life, see The Problems of Biology, by John Maynard Smith, Chapter 10.t To be honest, I don’t find it very convincing and I suspect that neither does Maynard Smith. It is a difficult problem and the initial start on it is, not surprisingly, less than fully convincing. With time we may have a better solution.

There are, however, other possibilities of non-supernatural development. Hoyle and Wickramasinghett and Crick seriously consider the prospect of extra-solar influence from some higher civilization elsewhere in the universe. Unfortunately both of these two sources handicap themselves by assuming that certain scientific verities of today are certain to be still believed in the far distant future.

In Alexandria a brilliant scientist named Ptolemy worked out a complete theory of the solar system and indeed of the universe. This theory was in complete accord with the facts as then known, and remained in accord with the facts discovered in the next 1,200 years. Today we look back at his work as intellectually a great achievement, but also as wrong.

Today we have another theory developed by an equally intelligent scientist, Einstein, which tells us that it is impossible to have anything move at a speed higher than that of light. Believers that this theory is permanently true have to believe that any interstellar communication would take remarkably long periods of time. That some other civilization could exceed the speed of light would appear as impossible to most scientists as a proposal to transmit messages faster than the Imperial Persian post would have seemed to Ptolemy.

Somewhat amusingly, the July, 2000 issue of Scientific American devotes three articles, with illustrations, to the possibility of interstellar communication, with the implicit assump- tion that other civilizations would use radio. They have a table showing in which parts of universe the SETI investigation tried but failed to detect radio signals. Other civilizations more than 100 years younger than ours or perhaps 2,000 years older could exist and would not have been detected.

When this article was nearing completion, however, I saw on the front page of the Washington Post* an article reporting that scientists had made light go much faster than the speed of light. This in a way was a grammatical error, but the meaning was clear. Einstein’s maximum speed, which was light in vacuum, had been greatly exceeded by light passing through a carefully doctored vapor. The particular method has no significant application to long-distance communication, but give the scientists time and the interstellar spaceships of science fiction may well be with us in the future.

The cases of interstellar guidance of evolution suggested by Hitch, Hoyle, and Wickramasinghe depend on an implicit theory that other civilizations in the universe are not much ahead of us. This may be true, but it may also be false. The elaborate SETI project for detecting other civilizations depends on the assumption that they are not very much behind or very much ahead of our civilization. This is rarely made explicit. Our scientists seem as convinced of the permanent truth of Einstein’s work as Ptolemy was of his.

It may not be entirely impossible, however, that some- where in the universe there is another civilization which is engaging in transmitting very simple life, perhaps cells or even something simpler. It has been demonstrated that some cells are capable of surviving in the high-radiation environment of nuclear reactors and hence radiation would not necessarily kill cells in empty space. Cells apparently can remain viable even when frozen in Antarctic ice sheets. Cells might be able to drift through space and eventually reach earth.

Life on our planet might be either an accidental byproduct of life somewhere else, or the result of a deliberate seeding of the universe. Some meteorites contain simple organic chemicals. To say they are organic does not imply that they come from life, but only that chemists would classify them as organic. Still this does show some feeble evidence that space transmission would be possible.

But why would some civilization do this? If the cells are simply drifting in space they must have started long, long ago. Thus the civilization that sent them must be millions of years older than ours. It should then be much more advanced than we or have finally exceeded the life span of civilizations, if such a thing exists. In any event, it’s hard to think of a motive for this activity. The radically different civilization might have radically different thought patterns than we do and hence we cannot expect to understand it.

The theory of distant origin· does not, however, solve the basic problem of the origin of life itself. It would presumably be as hard for life to start on another planet as on earth. Of course, even if the origin of life is very, very, very improbable, there might still be enough planets to allow it to take place on one or a few, supposing that there are, in fact, many, many planets close enough to earth. Since we have no real theory, only speculations as to the origin of life, this explanation can- not be ruled out. Indeed, Hitch’s speculation of tiny containers, in essence small spaceships, being deliberately sent out with a suitable set of organisms to start life cannot be ruled impossible, but I doubt that many of my readers will regard it as even remotely probable.

If there is continuous intervention, however, then one of the traditional questions about extra-earth civilizations is par-

Interestingly, although Freudianism is no longer much believed, it has not been replaced as a theory. Still, it is better to be without a theory than to believe firmly in the false theory.

ticularly relevant. “If an advanced civilization with space travel exists, why isn’t it here?” Of course, we cannot say for certain that some advanced civilization has not been visiting us from time to time. Almost all religions report supernatural phenomenon which might simply be the view taken by primitive people of the behavior of scientifically more advanced people. Primitive people, when brought into contact with modern civilization, frequently are convinced that they are seeing miracles. Perhaps the innumerable religious accounts of miracles in the past reflect the same phenomenon. Perhaps, but I doubt it.

This whole article deals with a problem which we have not solved, and it seems to me we should try to solve. The solutions I’ve listed above seem to me unlikely. If they seem unlikely to the reader, I suggest he try his own.